China reported Friday that the country’s gross domestic product growth for the third quarter of the year was 6%. Not since the first quarter of 1992, the first quarter for which the data is available, has the country reported such slow GDP growth.

In the second quarter of this year, the country’s GDP grew by 6.1%. Economists were expecting third-quarter growth of 6.2%. China’s trade war with the United States gets most of the blame.

Economist Martin Lynge Rasmussen, China economist at Capital Economics, told CNBC that it will take time for China’s exports (which were down 3.2% in dollar terms year over year in September) to recover:

Looking ahead, exports look set to remain subdued in the coming quarters. Meanwhile, import growth has slowed sharply in recent quarters and now looks unusually weak relative to economic growth. A partial rebound in headline import growth is therefore likely in the near term.

How bad is the slowdown in Chinese imports? Nearly 2.5-times worse than the slowdown in exports? Third-quarter imports dropped by 8.5%, according to a Reuters report, and the country’s total September trade balance reached $39.65 billion, more than 10% higher than forecast.

China has tried to offset this lack of import demand by injecting more money into the country’s banking system. That is not helping a lot because there’s not much demand for profitable infrastructure projects to spend the funds on. A Sichuan Development Guidance Fund official told the Financial Times, “There are not many economically viable projects for us to take on. We have plenty of bridges and roads already.”

Toll roads and bridges are profitable; sewage and water treatment plants less so, or even money-losing. That leaves Chinese lenders with a choice between slowing down investment, further constraining an already slowing economy, or start funding riskier projects, an option the central government itself has tried to stop for several years.

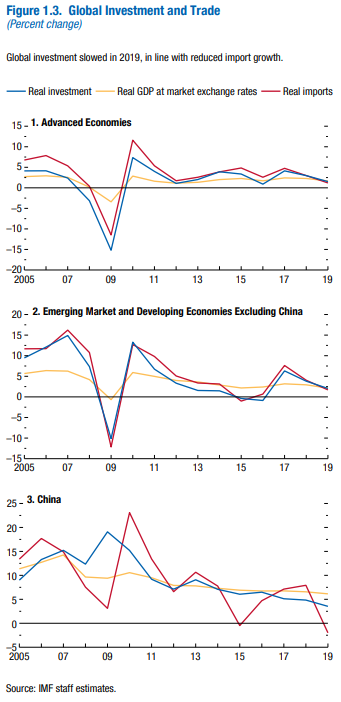

According to the October update to the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook, Chinese import growth lags about eight percentage points below the country’s real economic growth and well below import growth in the advanced economies (see chart 3 below).

What effect would a rebound in imports have on Chinese economic growth? Economist Brad Setser at the Council on Foreign Relations points out that lower investment means China will import less and that the problem is compounded by fewer exports also contributing to lower growth. Overall, the fall in Chinese exports due primarily to the U.S. tariffs was about 2% over the past year. Chinese imports have been shrinking by that amount annually for a decade.

In other words, China’s economic slowdown would benefit more from policies that encourage more imports, not tariffs that raise the prices of consumer goods and limit demand for imports. A secondary benefit, of course, would go to foreign exporters of goods Chinese consumers wish to buy.

Another takeaway is that an end to the U.S.-China trade war won’t fix China’s growth troubles, given the lack of profitable domestic investment opportunities. The International Monetary Fund forecast Chinese growth at 6.2% for this year and 6.0% for next year in its latest World Economic Outlook, but that assumes more investment, which implies more risk. That approach is not working now and has little chance of working any time soon as it is presently employed. China could be in for a tough slog.

Take Charge of Your Retirement In Just A Few Minutes (Sponsor)

Retirement planning doesn’t have to feel overwhelming. The key is finding expert guidance—and SmartAsset’s simple quiz makes it easier than ever for you to connect with a vetted financial advisor.

Here’s how it works:

- Answer a Few Simple Questions. Tell us a bit about your goals and preferences—it only takes a few minutes!

- Get Matched with Vetted Advisors Our smart tool matches you with up to three pre-screened, vetted advisors who serve your area and are held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests. Click here to begin

- Choose Your Fit Review their profiles, schedule an introductory call (or meet in person), and select the advisor who feel is right for you.

Why wait? Start building the retirement you’ve always dreamed of. Click here to get started today!

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.