The bull market is in full swing and the panic of late September and early October seems like a distant memory. The S&P 500 hit a new all-time high above 2,051 and the Dow Jones Industrial Average has recently hit an all-time high of 17,705. So, what does this mean for the Nasdaq at a 52-week high and decade high above 4,700, since it is not at an all-time high going back to the great tech bubble from 1999 to 2000?

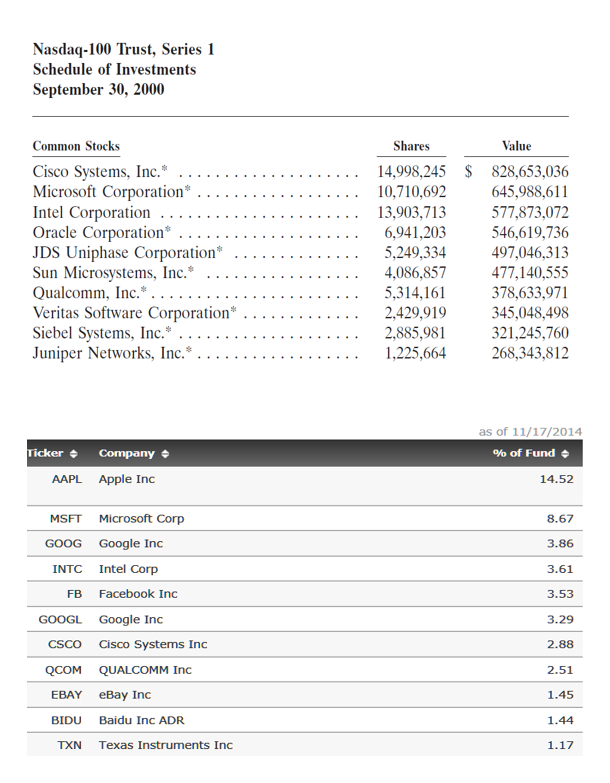

The analysis of today has very much to do with what has changed through time with the PowerShares QQQ (NASDAQ: QQQ) ETF, which tracks the Nasdaq 100, but it also has much to do with the likes of Apple Inc. (NASDAQ: AAPL) today versus Cisco Systems Inc. (NASDAQ: CSCO), Intel Corp. (NASDAQ: INTC) and Microsoft Corp. (NASDAQ: MSFT) of 2000 and today.

The first thing that has to be considered is what happened in the tech bubble in place from 1998 to 2000. The Nasdaq itself was under 2,000 in November of 1998. It rose above 3,000 in late 1999, and even went above 4,000 before the end of that year. Then it crossed above 5,000 very briefly in March of 2000 to a high of about 5,132 — and then Humpty Dumpty came crashing off the wall, with the Nasdaq back down under 3,000 by November of 2000.

ALSO READ: 10 Companies That Will Not Be Saved by the Bull Market Alone

As far as today’s market goes, the last time the Nasdaq was under 3,000 was December of 2012. Compare this to the great tech bubble in 1999 and 2000 and the gains are not even close. The reality is that valuations were unilaterally through the roof in 2000 and it was a runaway bull market.

It may feel like a runaway bull market now, but companies like Cisco, Intel and Microsoft are all valued at under 20 times earnings. Even the great Apple is valued at far less than 20 times earnings, with the reminder that Apple was effectively a nothing company in 1999 and 2000.

At the peak of the market in 2000, Cisco, Intel and Microsoft were the big three (followed by Oracle before it went to the NYSE), and their price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios were off the charts. The leaders were literally trading at 30, 40, 50 and even 100 times earnings, depending on what snapshot in time you use. Cisco is now valued at close to 12 times expected earnings, while Microsoft is valued at well under 20 times expected earnings.

Do these feel like runaway valuations on earnings? Another difference is that Apple, Cisco, Intel and Microsoft all have solid dividends now. By and large they paid no dividends back then. It just wasn’t expected of companies like it is now.

What else is different is that great companies like Google and Facebook were not even public back in 2000 — although to this day Amazon.com still has nothing short of a nosebleed stock market valuation. At the market peak, if you averaged the market cap of Cisco and Microsoft, it was about $500 billion. Now Apple is worth more than $675 billion, versus the current market caps of $400 billion for Microsoft and $136 billion for Cisco Systems.

ALSO READ: The 10 Safest High-Yield Dividends

Oracle and Juniper Networks are no longer in the Nasdaq 100 or the PowerShares QQQ ETF, as they have moved to New York Stock Exchange, but in 2000 they were a top 10 holding. Others that have been acquired and are gone from the Nasdaq 100 are Sun Microsystems, Veritas Software and Siebel Systems. JDS Uniphase was a top ten holding in the Nasdaq 100 at one point in 2000, and it is effectively a shell of its former self.

Comparing the Nasdaq and Nasdaq 100 of 2000 and 2014 is very difficult to do. The difference this time around is that valuations as a multiple of earnings are simply not bubbly for the leaders. In 2000 they were in an obvious bubble. Below we have a chart showing top Nasdaq 100 holdings from the third quarter of 2000 versus that of today.

NOTE: Price adjustments going back to the year 2000 may vary from source to source, as 14 years have passed. Index levels for current highs and lows come from Yahoo! Finance.

ALSO READ: Significant Changes in Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway Holdings

Take Charge of Your Retirement In Just A Few Minutes (Sponsor)

Retirement planning doesn’t have to feel overwhelming. The key is finding expert guidance—and SmartAsset’s simple quiz makes it easier than ever for you to connect with a vetted financial advisor.

Here’s how it works:

- Answer a Few Simple Questions. Tell us a bit about your goals and preferences—it only takes a few minutes!

- Get Matched with Vetted Advisors Our smart tool matches you with up to three pre-screened, vetted advisors who serve your area and are held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests. Click here to begin

- Choose Your Fit Review their profiles, schedule an introductory call (or meet in person), and select the advisor who feel is right for you.

Why wait? Start building the retirement you’ve always dreamed of. Click here to get started today!

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.