“They don’t give a sh*t about telephone guys. I mean it’s like us with the Ukrainians … they’d never bother a major over a few dead grunts.” Koulikov (Ron Perlman)

It was a throwaway line in an inaccurate World War Two film yet Enemy at the Gate’s quip about Russia’s troublesome past with Ukraine was on the money. The line was also oddly prescient, delivered just a few years before revolution and conflict came back to Ukraine. The 2022 Russian invasion was the latest chapter in a long and complex history between the two states. This article will examine the origins of Ukrainian national identity, the key events and context of the 20th century, and what led to the invasion.

Why This Matters

The ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine goes back a long way. Ukraine has only existed as an independent state for just over 30 years. Aside from a brief spell at the end of World War One, Ukraine was under Russian rule for centuries until 1991. To properly understand the current conflict, it’s important to know the historical context.

The 1800s: Autonomy and Repression

At its greatest extent, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s territory included most of modern-day Ukraine. However, the Commonwealth dissolved in the late 18th century by three partitions. After the final carve-up, Ukraine was divided between the Russian Empire and Habsburg Austria. Nationalist movements rose across Europe in the 19th century, and most emphasized linguistic ties.

In 1867, the Ausgleich (“compromise”) which established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary also granted limited rights to other minority national groups in the empire. Ukrainian language and culture grew through schools and political representation. Conversely, the much larger Russian-ruled portion of Ukraine elected to repress any expression of Ukrainian identity. The Ukrainian language, which the Russians called “Little Russian” and any nationalist political activity was banned.

The paternalistic view of Ukraine as ‘Little Russia’ is still apparent today. Vladimir Putin and other hardliners see Ukrainian identity as a Western imposition that doesn’t truly exist.

World War One

Ukraine was an important theater of the Eastern Front of World War One. Unlike the static lines of trenches on the Western Front, the Eastern Front was more open. Ukrainians fought on both sides of the conflict. 4.5 million fought for the Russian Empire while around 300,000 Western Ukrainians served the Austro-Hungarian army. Huge numbers of refugees and prisoners of war ended up in Ukraine. By July 1917 most of the fighting was over as Russia and Austria-Hungary fought to complete exhaustion. German forces advanced to the Dniester River virtually unopposed. The war caused a seismic shift in the economic and social conditions of a land devastated by the conflict.

1917-20: The Ukrainian Revolution

The Ukrainian Central Rada (UTsR) was formed in March 1917 as a movement for Ukrainian national liberation. The UTsR formed the Ukrainian government in June 1917 and passed a series of statements on Ukraine’s status. The first of the “universals” declared Ukraine would be an autonomous state within a democratic Russia. The fourth (and final) went much further, forming the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR) in January 1918.

The UNR agreed to peace with the Central Powers as part of the Brest-Livosk Treaty which pulled Russia out of the war. The price for peace was steep, Russia lost huge swathes of territory while Ukraine was compelled to send agricultural products to Germany and Austria. When the UNR couldn’t meet that obligation, Germany formed a short-lived puppet state in Ukraine in April 1918.

The UNR returned to power in December 1918 but inherited a precarious strategic position. World War One might have ended but there was no peace in Ukraine which became one of the epicenters of the Russian Civil War. When the dust settled, Ukraine was once again under Moscow’s yoke. In theory, Ukraine was one of the co-equal republics within the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) but in practice, things would be more complicated.

The Five-Year Plan and Holodomor

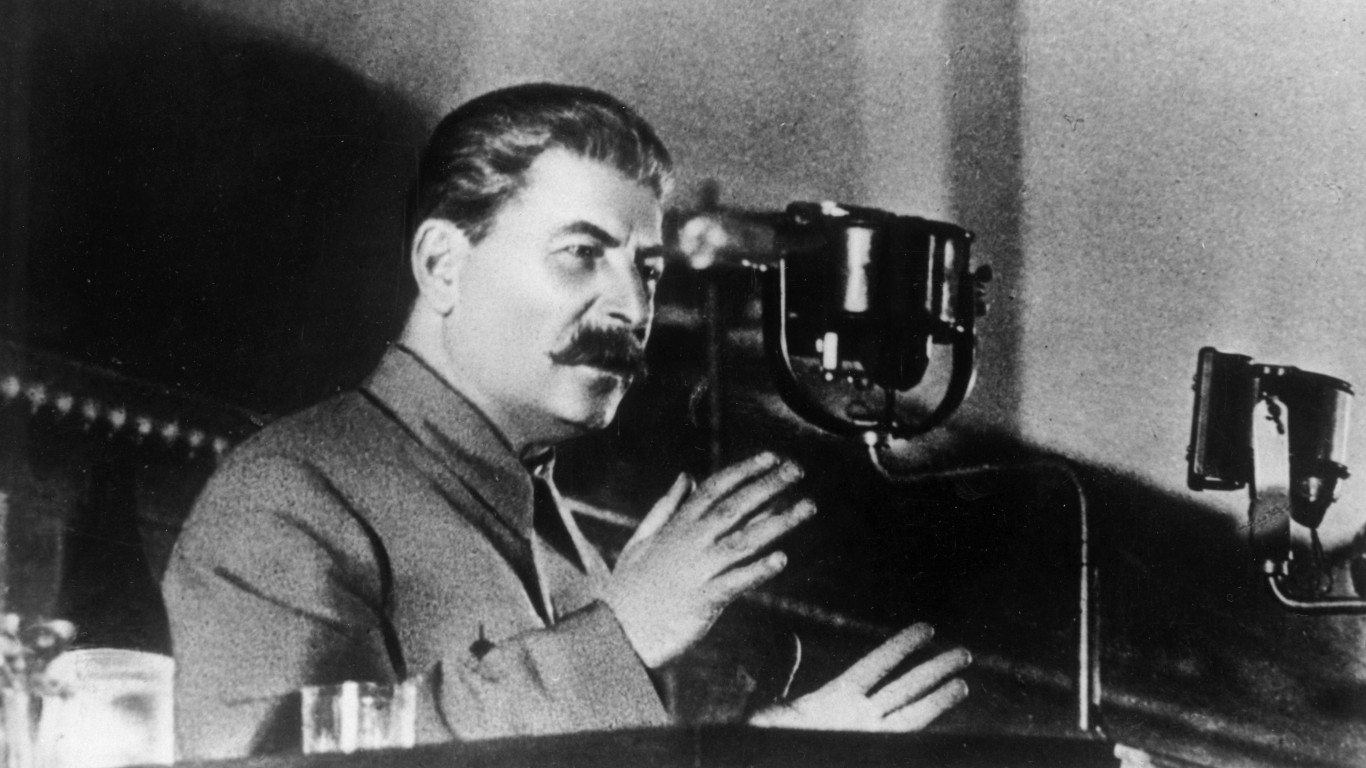

In 1928, the USSR created a five-year plan to industrialize on a massive scale. Collectivizing agricultural output was a cornerstone of the scheme but one that had disastrous consequences in Ukraine. As most farms in Ukraine were subsistence level, production quotas were impossible to meet. The few farmers who enjoyed a surplus were derided as kulaks and had their property seized. By 1932 the quotas were set at an unachievable level and the state dispatched collectors to root out hidden grain stores. Joseph Stalin used resistance by “saboteurs” as a pretext to crack down on the Ukrainian language and culture. Ukrainians were prohibited from leaving to escape the famine. At least four million Ukrainians, about 13% of the entire population, died during the Holodomor (“death by starvation”).

The impact of the Holodomor still affects Russo-Ukrainian relations today. The impact of the Holodomor still affects Russo-Ukrainian relations today. On November 28, 2006, Ukraine’s parliament recognized the Holodomor as a genocide. Russia maintains the famine was a nationwide tragedy and denies that genocide took place.

World War Two

As devastating as World War One was for Ukraine, World War Two was even worse. This was especially true for the 1.5 million Jews residing in Ukraine at the time. One of every four Jewish victims of the Holocaust died in Ukraine. Hitler’s goal of Lebensraum (“living space”) meant colonizing the “incalculable farmlands” of Ukraine.

Ukraine bore the brunt of Army Group South’s advance during Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941. Yet some viewed the advancing Germans as liberators and far-right ultranationalists participated in the Lviv Pogrom. Thousands served in the Galicia Division, an infantry division of the Waffen-SS primarily of Ukrainian volunteers. A veteran of the division caused considerable embarrassment to Canada’s parliament during a visit in September 2023.

Millions more Ukrainians fought for the USSR and died in droves to defeat the Nazis. After the Russians, Ukrainians suffered the heaviest casualties, about 1.6 million, in the Red Army. Civilians suffered under a brutal occupation that lasted until 1944 when over five million civilians died. The life expectancy for a Ukrainian male in 1941-45 was just 15 (up from 7 in 1933). In 1944, the advancing Soviet forces rounded up and expelled the entire Crimean Tartar community from their homes. Half died on the way to exile.

Vladimir Putin has used Ukraine’s complex World War Two experience to justify the 2022 invasion:

To this end, we will seek to demilitarize and denazify Ukraine, as well as bring to trial those who perpetrated numerous bloody crimes against civilians, including against citizens of the Russian Federation.

Crimea: 1954

In 1954 Nikita Khrushchev chose to mark the 300th anniversary of Ukraine’s incorporation into the Russian Empire with a gift. That present was Crimea. The peninsula was taken from the Ottomans by Catherine the Great in 1783. It seemed an odd move given that, thanks to the 1944 purges against the native Tartars, Russians outnumbered Ukrainians 3-to-1.

Khrushchev’s motives behind the award were partly due to his wish to move on from the brutal excesses of Stalin’s reign. Additionally, he held genuine affection for Ukraine having spent time working there in his youth and marrying a Ukrainian woman. In practical terms, the gesture didn’t have much impact on the Soviet Union but it would have serious unforeseen consequences in the future.

Chornobyl

The 1986 Chornobyl nuclear disaster was made all the worse by the Kremlin’s attempts to cover up the catastrophe. This was a violation of Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms aimed at improving transparency and accountability in the USSR. Just days later, in nearby Kyiv, the May Day celebrations went ahead despite the dangers. The episode served to further undermine confidence in an ailing regime and was yet another chapter in the troubled relations between Russia and Ukraine.

Independence and Guarantees

Ukraine declared its independence from the Soviet Union on August 24, 1991. A referendum was called for December 1st and 92% of ballots cast were for independence. Along with the rest of the world, Russia recognized Ukraine’s independence the next day. There were a few key questions to be answered in the coming years.

One of the first was exactly what to do with the vast number of nuclear and conventional weapons housed in Ukraine. With serious concerns about the loyalty of the men in charge of them, Ukraine opted to part with its nuclear arsenal in exchange for financial aid from the United States and guarantees from Russia. Ukraine signed the Budapest Memorandum in December 1994. Little faith was placed in Russia holding up its side of the bargain. Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma remarked:

If tomorrow Russia goes into the Crimea no one will even raise an eyebrow. Besides…promises, no one ever planned to give Ukraine any guarantees.

Crimea and Donbas: 2014-2022

As the earlier section noted, Ukraine’s connection to Crimea was tenuous. In the 1991 independence referendum, Crimea and Sevastopol City were the major outliers. Where most oblasts voted overwhelmingly for independence, the results were much closer in the peninsula. Many in Crimea favored separation and reintegration with Russia, Yuri Meshkov, a pro-Russian separatist, won the 1994 Crimean election to become its first president. A restrained response from Kyiv helped to ease the tensions. The 1996 Ukrainian Constitution granted Crimea autonomous status.

The Crimea question reared its head again in February 2014. Ukraine’s President Viktor Yanukovych was forced out of office by mass protests after he went back on a deal to join the European Union. Considered a friend of Moscow, Yanukovych’s removal drew outrage from Vladimir Putin. Russia annexed Crimea a few days later. Russian military personnel surrounded the airports and assembly. A disputed referendum claimed 95% of Crimean voters backed the annexation.

Around the same time, separatist protests in the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine escalated into a full-blown conflict. Russian-backed forces seized territory in Donetsk and Luhansk. With a weakened military and no leader, Ukraine’s response to the crisis was sluggish. The first Minsk Protocol in 2014 was supposed to end the fighting but soon collapsed. A second agreement in 2015 also in Minsk was supposed to provide a roadmap to peace. The deal was undermined when Putin recognized the independence of Donetsk and Luhansk. Low-level fighting continued up to the 2022 full-scale invasion by Russia which subsumed the conflict.

Conclusion

The antipathy between Russia and Ukraine goes much further than the 2022 invasion. Going back to its incorporation into the Russian Empire, Ukraine has never truly been accepted as a distinct national identity by Russia. That paternalistic view of Ukraine as “Little Russia” is still apparent in modern discourse. Similarly, the abject horrors Ukraine experienced in both World Wars and under Soviet rule still inform the present. The outcome of the current conflict is yet to be determined and future predictions tend to be dangerous grounds for the historian but one thing that can be stated with any certainty is that this story is far from over.

It’s Your Money, Your Future—Own It (sponsor)

Retirement can be daunting, but it doesn’t need to be.

Imagine having an expert in your corner to help you with your financial goals. Someone to help you determine if you’re ahead, behind, or right on track. With SmartAsset, that’s not just a dream—it’s reality. This free tool connects you with pre-screened financial advisors who work in your best interests. It’s quick, it’s easy, so take the leap today and start planning smarter!

Don’t waste another minute; get started right here and help your retirement dreams become a retirement reality.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.