The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) turned 75 this year. Since its inception in 1949, NATO has grown from 12 founding members to 32 nations today. Though remarkably successful and enduring, the alliance has always had internal tensions to manage. As NATO expands, so too do its points of contention between members. Some are minor squabbles that should have amicable solutions, others are more complex and difficult to untangle. This article will examine the points of contention between NATO members and what the future may hold.

Why This Matters

With ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza and heightened tensions in the Pacific, NATO’s unity has seldom been more important. NATO’s future status is a key issue in the US presidential election as the candidates present different visions of how the alliance will function.

France and Germany

An important member of NATO, France has a complex history with NATO. In 1966, France left NATO’s integrated command structure but stayed in the alliance. Paris still participated in NATO operations and rejoined the command structure in 2004. More recently, France has been at odds with Germany over the war in Ukraine.

Emmanuel Macron’s bellicose rhetoric towards Russia is at odds with Olaf Scholz’s more restrained posture. Macron’s suggestion he’d send troops to Ukraine drew a rebuke from his German counterpart. Macron also took issue with the non-lethal aid sent to Ukraine in the early part of the war, disdaining Germany’s offer to send “sleeping bags and helmets.”

The two leaders have since made public shows of support. However, gains made by far-right populists in Germany could undermine Berlin’s continued support for Ukraine. France and Germany may soon be at odds again.

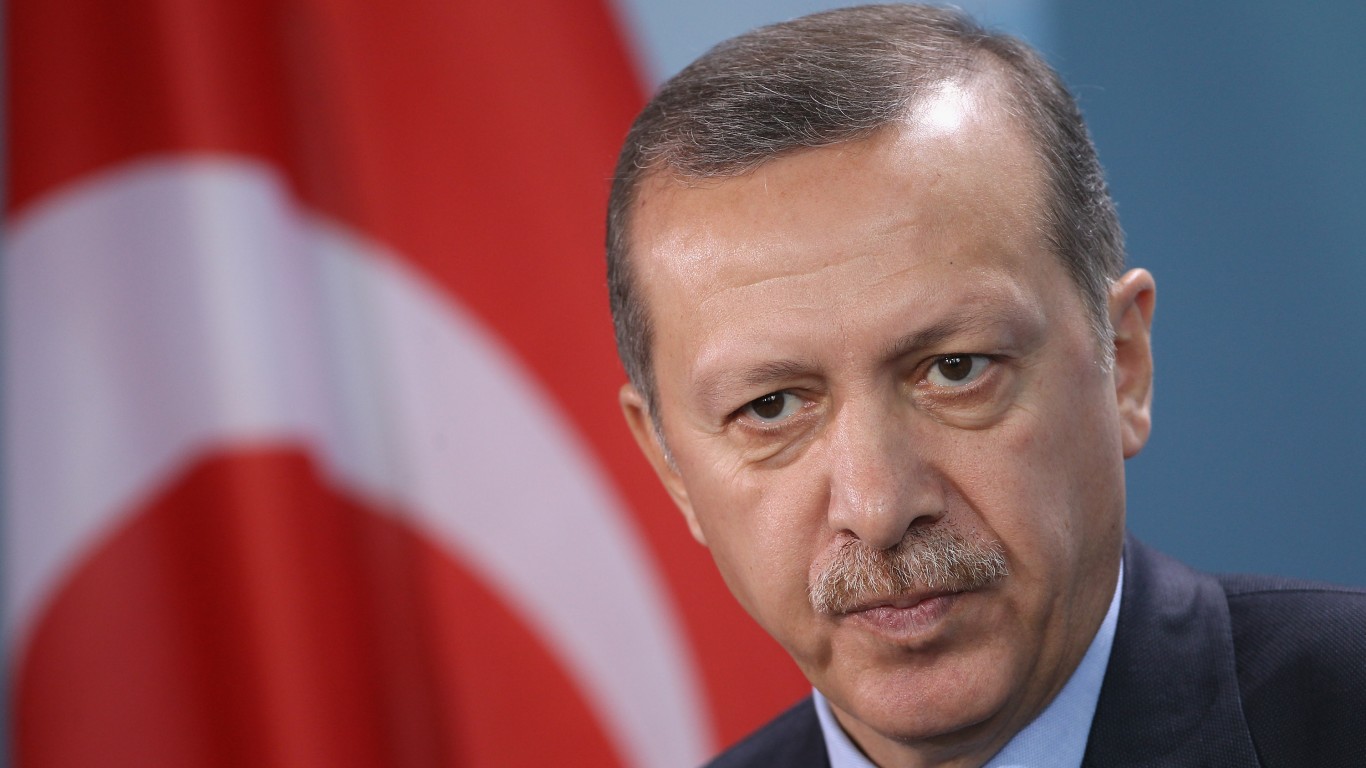

Greece and Turkey

Turkey and Greece joined NATO together in 1952. The two nations have a complex and often adversarial history. Greece and Turkey (as its Ottoman predecessor) fought several wars in the 19th and early 20th century. The Treaty of Lausanne (1923) established the modern borders of Greece and Turkey and led to a warming of relations in the interwar years. In World War Two, neutral Turkey helped relieve a famine in Axis-occupied Greece. Turkey shipped over 50,000 tons of aid to Greece from 1941-46.

Whatever goodwill developed between Athens and Ankara broke down after the Second World War. Greece regained control from Italy over several islands in the Aegean Sea in 1947, many of these tiny islands are uninhabited but within striking distance of Turkey’s coastline. In January 1996 the two countries almost went to war over an incident on the tiny, unpopulated island of Imia (Kardak in Turkey). The US resolved the dispute but tension ignited once more when the Greeks shot down a Turkish F-16 in October.

The other major bone of contention between Greece and Turkey is Cyprus which has substantial Greek and Turkish communities. The troubles stretch back to the 1950s but intensified in 1974. Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974 after a Greek-backed coup. Today the island is divided by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and the Republic of Cyprus. 50 years later, the Cyprus Problem has yet to be resolved.

Turkey’s cordial relations with Russia, interest in joining BRICS, and careless comments about Israel are other areas of concern. Turkey has a great to offer NATO but it is a complicated relationship that requires some mending.

Hungary

Relations between Hungary, the European Union, and NATO have grown strained. Hungary’s far-right leader Viktor Orban is one of the few European nations with good relations with Moscow. Budapest doesn’t support sanctions and has frequently held up financial and military aid packages to Kyiv. Hungary insists its opposition to Ukraine is rooted in concerns over the country’s treatment of its ethnic minorities. To the irritation of other EU and NATO members, Orban met Putin in July 2024 and has called for an immediate ceasefire.

Though Hungary pledged not to veto Ukraine’s bid, Orban insists Budapest won’t participate in any NATO efforts to aid Kyiv:

We do not approve of this, nor do we want to participate in financial or arms support (for Ukraine), even within the framework of NATO

North Macedonia

In 2018, Greece and North Macedonia signed the Prespa Agreement to bring an end to a long dispute over the country’s name. Greece objected to the former Yugoslavian republic referring to itself as Macedonia. Athens held up Skopje’s NATO membership until the matter was resolved.

The treaty seemed to settle the dispute but the new center-right government in North Macedonia appears to be going back on the deal. The new President of North Macedonia, Gordana Siljanovska-Davkova, angered Greece by referring to her country as ‘Macedonia’ in her oath of office.

Bulgaria also has issues with North Macedonia. Sofia is holding up Skopje’s ascension to the European Union over a dispute over recognizing a Bulgarian minority and other historical and cultural issues.

Poland

Warsaw’s commitment to NATO is hardly in doubt, Poland spends a greater proportion of its GDP on defense than any other member, but relations with Germany are a cause for concern. Germany and Poland certainly have a difficult history. The Law and Justice Party (PiS) was in power from 2016-23 and is known for its anti-German posture. PiS lost ground in the 2023 elections and Donald Tusk’s Civic Platform (PO) offered the chance for a fresh start with Berlin.

However, despite some productive talks in June, Warsaw and Berlin are again at odds. Poland refused a German request to extradite a suspect in the Nord Stream sabotage. Suspicions of Poland’s involvement have soured relations between the two countries. Tusk also spoke against Germany’s decision to impose tighter controls at its border.

Slovakia

Slovakia’s stockpile of Soviet-era weaponry from its days in the Warsaw Pact proved very useful to Ukraine in the early stages of the war. While the donated BMPs and MiG-29s are no match for modern hardware, they were already familiar to Ukraine’s armed forces and available in a pinch. Unfortunately for Ukraine, Slovakia appears to moving in a similar direction as Hungary.

In the 2023 Slovakian elections, former Prime Minister Robert Fico returned to power for the third time. He pledged to end support for Ukraine and refused to participate in the Czech-led initiative to purchase artillery shells for Ukraine. However, Slovakian citizens contributed over €1m to the effort in less than 48 hours.

Fico has called for Ukraine to give up territory to secure peace and vowed to block Kyiv’s NATO bid. In January 2024, Fico said admitting Ukraine into NATO would risk instigating a World War.

The United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is a key member of NATO and one of few to consistently meet the 2% spending target. Britain has had issues with other members of NATO in the past. Iceland and the UK “fought” over fishing rights in the so-called Cod Wars in a series of minor confrontations in the North Atlantic from 1952-1976. Iceland prevailed in all three disputes.

Britain’s commitment to the alliance is not under question and the Labour Party’s victory in the 2024 election will not significantly change that outlook. However, the fallout from the UK’s referendum to leave the European Union (EU) causes some complications. Most other European NATO members are also part of the EU and Britain’s choice makes cross-border trade and immigration a little more difficult.

Gibraltar’s status is a long-standing issue between Spain and the United Kingdom which Brexit has exacerbated. The small peninsula occupies a key strategic position that Britain has spilled a great of blood and treasure to retain over the centuries. Spain proposed a joint administration with Britain but Gibraltar’s population has made it clear in multiple referendums that they wish to remain British. However, residents of “the Rock” are equally adamant in their desire to stay in the EU. Negotiations between London and Madrid on this issue are ongoing.

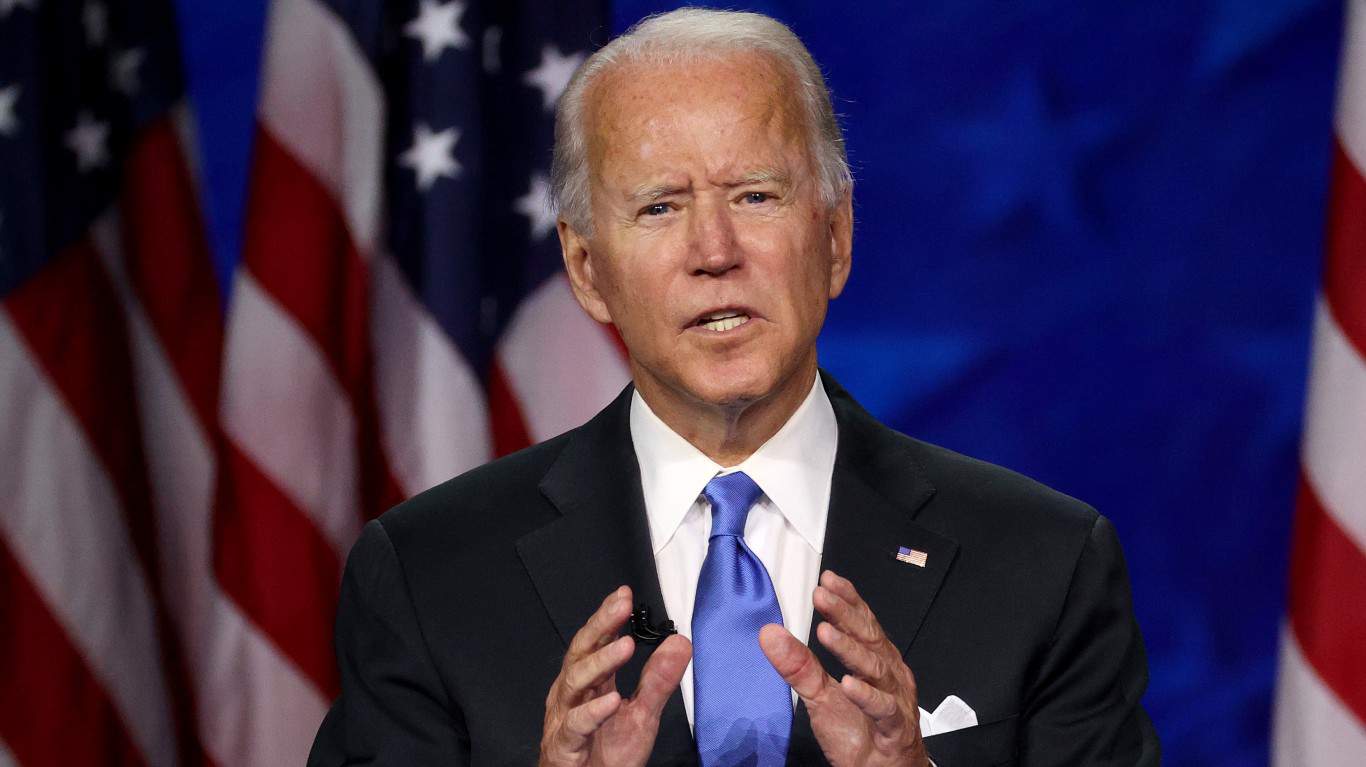

The United States

The USA is the largest defense spender in NATO by far and this disproportionate share of the burden is a long-standing issue for Washington. This discrepancy was addressed at a 2014 summit in Wales when members agreed to spend at least 2% of their GDP on defense. At the time, only the United States, United Kingdom, and Greece were at that level. Progress was slow and then-presidential candidate Donald Trump made a great deal about NATO members not pulling their weight in his campaign.

Relations between the United States and other members of NATO were strained during Trump’s term in office. Despite threats to pull out, the United States remained in the alliance. Joe Biden moved to restore America’s place in NATO during his term but the long-term future of the coalition is still in doubt. While most NATO members now meet their spending obligations, some are still lagging. This discrepancy is a subject of the 2024 presidential election.

The Harris-Walz ticket wants to stay the course chartered by the Biden administration, to build cooperation and lead. The Trump-Vance ticket is more skeptical and pledges to take a more hands-off approach, especially with Ukraine. Trump has mentioned a two-tiered system where those who don’t meet the target will not receive American assistance if attacked. While this could be campaign bluster, it has sufficiently worried other NATO members to take measures to mitigate the effects of a second Trump term.

Ultimately, it will be up to the American voters in November to determine how NATO will function in 2025 and beyond.

Conclusion

NATO’s internal tensions are complex and multifaceted. Some stem from very long-standing historical grudges and territorial disputes. Others reflect recent political changes at home and flexibility in foreign affairs that can disrupt the alliance’s unity. With so many members spread out over such a wide geographical area, disagreements are to be expected. The rise of right-wing populism in Europe has coincided with a rise in NATO skepticism.

Though it is an international organization, each member’s domestic policies have a huge bearing on how each nation functions within the alliance. The war in Ukraine is straining relations among some members and undermining unity. Hungary and Turkey’s friendly ties with Moscow have caused tension. Similarly, Slovakia’s pivot away from supporting Ukraine and pledge to veto Kyiv’s future membership is a situation that will have to be addressed carefully. Germany, France, and Poland, the so-called “Weimar Triangle” have issues with one another but are showing signs of working out their differences.

The biggest test of NATO’s future comes this November. A Harris victory will mean a continuation of her predecessor’s efforts to strengthen the alliance and even with a divided legislature, there should be enough Republicans on board to work out a deal. Conversely, a Trump victory will likely weaken NATO. Even if a complete withdrawal is unlikely, the hands-off approach to Eastern Europe will probably lead to an unfavorable settled peace and pose serious questions for NATO’s future.

Still, NATO has shown flexibility towards its members in the past and will have to do so in the future if it wishes to last another 75 years.

Get Ready To Retire (Sponsored)

Start by taking a quick retirement quiz from SmartAsset that will match you with up to 3 financial advisors that serve your area and beyond in 5 minutes, or less.

Each advisor has been vetted by SmartAsset and is held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests.

Here’s how it works:

1. Answer SmartAsset advisor match quiz

2. Review your pre-screened matches at your leisure. Check out the advisors’ profiles.

3. Speak with advisors at no cost to you. Have an introductory call on the phone or introduction in person and choose whom to work with in the future

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.