Military

These Rural Areas in America Are in Greater Danger of Nuclear Attack Than New York City

Published:

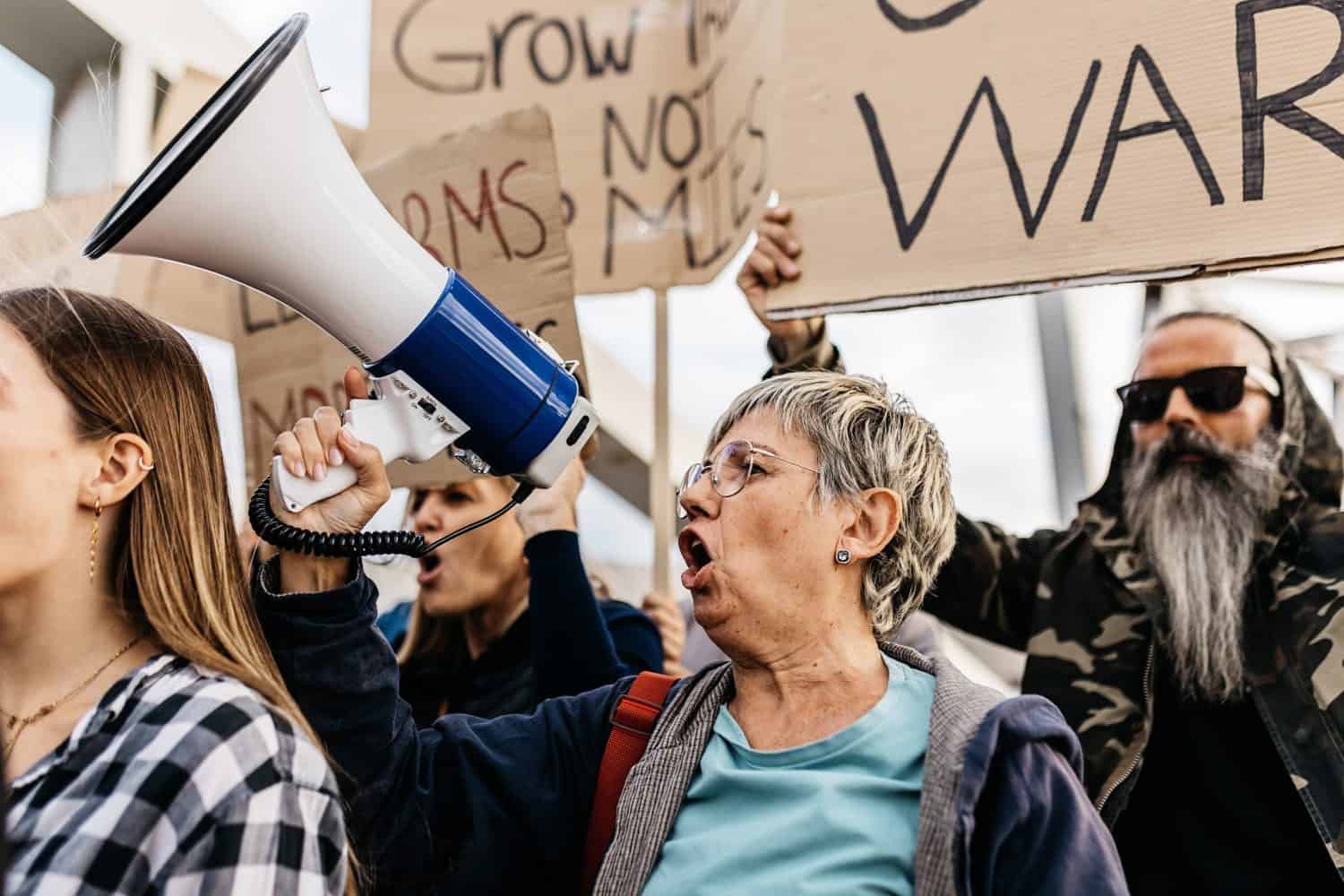

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has rattled many people’s nerves, especially as the United States and its NATO allies have provided funding, training, and advanced weaponry to Ukraine. Most recently, members of the Western alliance have begun lifting restrictions on the use of their weaponry, allowing Ukraine to strike deep into Russia itself. Some fear this could escalate into a nuclear exchange between Russia and the U.S. If you think you’re safe living in a rural area, think again. In fact, some of the most rural and isolated parts of the country may be in greater danger of attack than New York City or other urban targets.

24/7 Wall St. Insights

You might assume that any nuclear conflict would automatically escalate to a full-on nuclear exchange with both cities and military assets being targeted. This is not necessarily the case. War planners look at various scenarios that can include either countervalue strikes (attacks on cities and other non-military assets) or counterforce strikes (attacks on military command and control, bases, and assets.

An enemy might choose countervalue targeting if their goal was to destroy the United States government and cripple the nation economically and socially. Experts suggest that New York, Washington D.C., Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, Miami, and Philadelphia would be some of the most valuable targets in terms of their importance as centers of finance, government, industry, and trade.

A successful countervalue attack on these types of targets could set the country’s development back by a century and might even lead to the country’s breakup into multiple independent states. However, any country that attacked these kinds of targets could expect the same to be done back to them, so it would be a suicidal choice. Nonetheless, it is a choice an irrational enemy might make, or one who felt the survival of their country was already threatened.

Wargame scenarios do not automatically assume that an enemy would resort to countervalue targeting. An enemy might take the risk of trying to disable American nuclear assets and command and control without targeting cities, at least initially. A first-wave surprise attack might try to knock out the United States’ ability to launch a response. Then an enemy could threaten to begin taking out cities unless the country met the enemy’s demands. The populations of threatened U.S. cities might rise up to demand the government make peace on any terms to protect their lives and property.

The United States has some capability to shoot down limited numbers of ballistic missiles before they reach their targets, but not large numbers of them at once. The most effective strategy we have to protect our capability for nuclear retaliation is to maintain a “strategic triad” including ground-based ICBMs, nuclear-capable aircraft, and submarine-launched missiles. This is intended to ensure that even if an enemy delivered a knockout blow to one part of the triad, the others could survive to deliver a devastating retaliatory strike. Whether that retaliation would actually be carried out, however, is a political decision. The country’s leadership might decide deescalation would allow the U.S. a better chance of survival as a nation than proceeding to a world-shattering full-scale nuclear exchange.

No matter what the American strategy and capabilities are, deterrence is only effective if potential enemies believe we will use what we have. Some factors that could undermine the deterrent effect of the U.S. nuclear arsenal are things like withdrawing from alliances, reducing U.S. overseas troop deployments, substantial reductions in military spending, lack of clear and assertive diplomatic engagement, and political disunity and social unrest at home.

If deterrence failed and an enemy attempted a counterforce attack, these are some of the rural areas that could be affected by large strikes on significant nuclear targets, while sparing urban centers like New York City. All of this information is available in the public domain.

The safest places in the United States in the event of a nuclear war are remote from targets, such as big cities or military bases, but are also upwind from such targets so they are less likely to be affected by nuclear fallout. Some of the less-populated Hawaiian islands, Alaska, or the Rocky Mountains might be good bets for surviving the initial effects of a nuclear exchange.

If the war were extensive enough to cause a collapse of the American society and economy, then it would be important to live in a place with access to natural freshwater sources and farmland or wild game to be able to feed yourself. In the event of a massive nuclear exchange that caused extreme climate change, you would no doubt want to get as far south as possible where the weather might be warmer and more survivable until sunlight-blocking clouds of smoke and ash clear.

All of which leads to the obvious conclusion: the best way to keep people safe in a nuclear war is not to fight one at all.

Retirement can be daunting, but it doesn’t need to be.

Imagine having an expert in your corner to help you with your financial goals. Someone to help you determine if you’re ahead, behind, or right on track. With SmartAsset, that’s not just a dream—it’s reality. This free tool connects you with pre-screened financial advisors who work in your best interests. It’s quick, it’s easy, so take the leap today and start planning smarter!

Don’t waste another minute; get started right here and help your retirement dreams become a retirement reality.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.