Special Report

50 Strangest Town Names in America (and Where They Came From)

Published:

Last Updated:

There are no rules for naming towns. Some are christened, reasonably enough, after their founders or early patrons. Others are named for monarchs or political figures, or for saints — for instance, St. Louis and St. Petersburg, Florida. (Such names in the West often take the Spanish form, as in San Francisco or Santa Monica.) Other places have monikers, saintly or otherwise, based on French, German, Scandinavian languages, or various other tongues.

Some town names reflect their geographical situations or nearby features or reference places their settlers or early residents left behind. Some, though, are just made up. These often have intricate, sometimes amusing, sometimes unlikely origin stories. And these are usually the funniest, most unlikely, or just plain strangest ones.

What makes a town name strange? That’s a matter of opinion, of course. Residents of some places brag or joke about what they’re called; others dispute or deny the etymologies. That’s their right. We don’t offer this list to make fun of any place name. We just enjoy the unexpected, and we’re pretty confident that these are all town names that will make you think twice.

Click here to see the 50 strangest town names in America.

Click here to see our full methodology.

1. Accident, Maryland

> Municipal status: Town

> Population: 289

In 1786, when land speculator William Deakins, Jr., was granted the patent, or official land grant, to the tract where this town now stands, he called it “Accident.” According to local lore, this was because he and another speculator, Brooke Beall, had accidentally surveyed the same tract simultaneously.

[in-text-ad]

2. Arab, Alabama

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 8,247

The city of Arab (pronounced “ey-rab”) has no Middle Eastern connections. It got its name through a typographical error. After a village grew up around mid-19th-century settler Stephen Tuttle Thompson’s farm, Thompson asked the federal government to open a local post office. He offered three possible names for it: Ink, Blue Bird, and Arad, the last of these for his son Ranson Arad Thompson. Whoever processed the application chose Arad — but misspelled it “Arab,” and the name stuck.

3. Bad Axe, Michigan

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 3,024

Planning the first state road through Michigan’s Huron County in the early 1860s, surveyors Rudolph Papst and George Willis Pack established a camp site where the city is now. They called it “Bad Axe Camp,” after an old axe they found there. They used the name both in their record of their journey and on a sign on the trail. By the time Papst returned to the area following the Civil War, the name “Bad Axe” was being used officially on local maps.

4. Bald Knob, Arkansas

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 2,906

Local legend maintains that Spanish explorer and conquistador Hernando de Soto was the first to describe the immense rock outcropping above the site of this city as a “bald knob” (though presumably in Spanish). One of the community’s founders, Benjamin Franklin Brown, posted a sign reading “Bald Knob” along the railroad tracks in the early 1870s. Beginning in 1877, the layered stone knob itself was quarried for railroad ballast. The following year, Bald Knob got its first post office, firmly establishing the name.

[in-text-ad-2]

5. Ball Club, Minnesota

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 186

Nothing to do with baseball, Ball Club is named for Ball Club Lake, on which it sits. The lake in turn was so named because its shape supposedly resembled clubs used by local Ojibway to play the stickball game that evolved into modern-day lacrosse.

6. Bayonet Point, Florida

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 25,794

This dangerous-sounding moniker in fact derives from a plant called Spanish bayonet, a kind of yucca, which grew on the site. The name appears for the first time in 1900 on a Florida State Geological Survey map.

[in-text-ad]

7. Bear, Delaware

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 19,904

A Colonial-era tavern called The Bear, located somewhere in the area, lent its name to this community. George Washington is said to have stopped at the tavern, which shut down in 1845 and was later torn down. Its name survived on the local railroad station and then the post office.

8. Between, Georgia

> Municipal status: Town

> Population: 275

One George Schaeffer, whose wife was the postmaster of nearby Monroe, reportedly chose the name for this community because it was approximately midway between Monroe and the town of Loganville.

9. Blue Ball, Pennsylvania

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 856

In the early 18th century, an Irish immigrant named John Wallace opened an inn — which later became a hotel — at a crossroads of two trails (now Pennsylvania routes 23 and 322). Wallace suspended a large blue ball from a post outside and called the place The Sign of the Blue Ball. The town’s original name was Earl Town, but locals started calling it Blue Ball, and the name was officially changed in 1833.

[in-text-ad-2]

10. Boring, Oregon

> Municipal status: Unincorporated

> Population: 8,000

Stifle that yawn. The community of Boring — originally Boring Junction — was named for Civil War veteran William Harrison Boring, who donated the land for its first schoolhouse and lent his name to the local hotel and Grange chapter, among other things.

11. Cal-Nev-Ari, Nevada

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 128

This site was originally known as Stage Field and was an airfield for World War II army training center Camp Ibis. After the camp was closed, an airport operator, Slim Kidwell, flew over the area and thought it had development possibilities. He and his wife, Nancy, took possession of the property in 1965, naming it in recognition of its home state and its proximity to the California and Arizona borders. They built an airstrip, casino, motel, restaurant, and bar, among other features.

[in-text-ad]

12. Chunky, Mississippi

> Municipal status:

> Population: 440

Chunkyville was village established before 1848 on the site of a former Choctaw settlement called Chanki Chitto. In 1861, after it was announced that planned railroad tracks would pass several miles north of the village, most of its citizens moved close to where it would pass and called their new town simply Chunky.

13. Coy, Arkansas

> Municipal status: Town

> Population: 105

The founder of this town wasn’t trying to be cute. His name was Lucien W. Coy. A Civil War veteran (on the Union side), he became a money lender and land speculator after the conflict ended. His wife, Abby, purchased the land on which Coy stands in 1896, later selling it to one Andrew Jackson Walls. Walls and his partner, W. E. Coleman, built a cotton gin and a store on the property in 1903, and this became the nucleus of the town.

14. Cucumber, West Virginia

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 70

This community takes its name not from the familiar vegetable, but either from the so-called cucumber tree (sometimes written cucumbertree), Magnolia acuminata, which grows in the region, or from Cucumber Creek — itself likely named for the tree.

[in-text-ad-2]

15. Cut and Shoot, Texas

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 1,543

Local legend has it that the name of this city derives from a disagreement in 1912 at the local church, with churchgoers arguing over land claims, or steeple design, or who the preacher should be. Whatever the source of the dispute, a small boy at the scene is said to have announced his annoyance with the goings-on by saying “I’m going to cut around the corner and shoot through the bushes in a minute.” Exactly when locals decided to name their settlement after the statement is not recorded.

16. Ding Dong, Texas

> Municipal status: Unincorporated

> Population: 400 (est.)

In the 1930s, a couple named Bert and Zulis Bell ran a store in Bell County, in the Texas Hill Country, between Killeen and Florence. (It is now officially within the city of Killeen.) The county wasn’t named for them, but for Peter Hansborough Bell, a 19th-century governor of Texas. Ding Dong, though, was named for them in a way. In making a sign for their emporium, the painter they hired elected to add images of two bells, bearing the couple’s names, to the sign. Under them, he painted “Ding Dong” as a joke — and that became the name of the community.

[in-text-ad]

17. Dry Prong, Louisiana

> Municipal status: Village

> Population: 524

A prong, which we usually think of as the tine of a fork or part of an electrical plug, can also be one arm of a forked river. This village most likely takes its name from a creek that powered the local sawmill most of the year but dried up every summer.

18. Eek, Alaska

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 472

Eek’s name may suggest the sound a frightened person makes, but it’s actually an anglicized corruption of the locality’s Central Yup’ik name, Ekvicuaq — literally ˚little cliff.”

19. Embarrass, Wisconsin

> Municipal status: Village

> Population: 572

The French verb embarrasser can mean “to hamper,” “to stop,” or “to embangle [entangle].” The word is said to have been attached to this place by French-Canadian lumberjacks who found the nearby river almost impassable.

[in-text-ad-2]

20. Flasher, North Dakota

> Municipal status:

> Population: 363

This city, founded by William H. Brown in 1902 and settled by Russian-German immigrants, was originally called Iowa City and later Berrier (after the man who was to be postmaster). Postal officials rejected both, so Brown named it instead for Mabel Flasher, his niece and secretary.

21. Foot of Ten, Pennsylvania

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 674

This community takes its name from its position at the base of the Number 10 plane (or incline) of the historic Allegheny Portage Railroad. The railroad was part of the network of canals and railways that made up the Pennsylvania Main Line of Public Works, which connected Philadelphia and Pittsburgh for much of the 19th century.

[in-text-ad]

22. Frankenstein, Missouri

> Municipal status: Unincorporated

> Population: 40 (est.)

There is no evidence that this community was named for Mary Shelley’s mad scholar (or for the man-creature he created, widely and mistakenly also called Frankenstein). The town was mostly likely so christened in honor of one Gottfried Franken, who donated land to the town in 1890. The tract became known as Franken Hill. “Stein” can mean rock, so the name may have simply been a fancy way of honoring the donor for his “rock,” or hill.

23. Gas, Kansas

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 664

In 1893, drillers discovered natural gas deposits here, which were described by Gas founder E. K. Taylor in local newspaper the Iola Register as “[N]atural Resources that will erect and maintain a City as solid as the Rock of Gibraltar.” Taylor planned the town, which he dubbed Gas City, and started selling residential and business lots in 1898. When he applied for a post office the following year, postal authorities asked him to drop “City” from the name, which he did.

24. Hideout, Utah

> Municipal status: Town

> Population: 847

Hideout is a new town, established only in 2008. It’s named for an old landmark nearby, Hideout Canyon, which was called that because it was a popular hideout for rustlers and other outlaws in earlier days.

[in-text-ad-2]

25. Ho-Ho-Kus, New Jersey

> Municipal status: Borough

> Population: 4,139

Where this New Jersey borough gets its name is a matter of some dispute. One theory links it to early Dutch settlers, who may have commented on its hoge eiken (hoge aukers, according to some versions), or high oak trees. More likely, it is a Native American term describing some feature of the local topography, flora, or fauna — possibly a Delaware word usually rendered as “mehokhokus,” meaning “red cedar.”

26. Hungry Horse, Montana

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 661

Hungry Horse and the nearby Hungry Horse Dam were named for two draft horses who got lost in the snow in the winter of 1900-01 and were found weak and starving a month later. They were nursed back to health.

[in-text-ad]

27. Jot Em Down, Texas

> Municipal status: Unincorporated

> Population: 10

This unincorporated community has also been known at various times as Mohegan, Muddig Prairie, and Bagley. Jot Em Down (or Jot ‘Em Down, or Jot-Em-Down) is a reference to the store in the old “Lum & Abner” radio comedy series. A local resident, Dion McDonald, opened a real store in town in 1936 and gave it that name, and the town later adopted it.

28. Likely, California

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 63

In 1878, locals were asked to find a new name for their post office, after the Post Office Department rejected its old name, South Fork. They suggested three alternatives, each of which was turned down because they duplicated names of other post offices elsewhere in California. When somebody remarked that they would likely never find a name, somebody else supposedly spoke up and said, “It is not likely that there will be another post office in the state called ‘Likely.’” They submitted that, and it was accepted.

29. Mexican Hat, Utah

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 31

Founded by an oil speculator in 1908, this community is named for a rock formation about two-and-a-half miles to the northeast that is thought to resemble, from certain angles, a sombrero — a Mexican hat.

[in-text-ad-2]

30. Monkeys Eyebrow, Kentucky

> Municipal status: Unincorporated

> Population: 11 (est.)

According to its unofficial historian, Joe Culver, a former U.S. Department of Energy public relations man, this community’s name is sometimes rendered as Monkey’s Eyebrow or Monkey Eyebrow. He reports that there are several stories about why it got called that, but his preferred version is that western Kentucky vaguely resembles the profile of a simian’s face, partially outlined by the Ohio River — and Monkeys Eyebrow sits where, well, the monkey’s eyebrow would be.

31. Ninety Six, South Carolina

> Municipal status: Town

> Population: 2,000

Home of a National Historic Site, and a key Revolutionary War battle site, legend has it that Ninety Six got its name in the 18th century, when a Cherokee woman named Issaqueena rode 96 miles from Keowee, the Cherokee capital, to a trading post on the site to warn the settlers of an impending attack by her people on the settlers.

[in-text-ad]

32. Normal, Illinois

> Municipal status: Town

> Population: 54,534

There’s a joke that this town, originally called North Bloomington, was named for its supposed founder, Abner Normal, known as Ab (get it?). In reality, it was named that because the new state university opened there in 1861 was described as a normal school (an old name for a teachers college).

33. Okay, Oklahoma

> Municipal status: Town

> Population: 522

This Oklahoma town has had a number of names, or at least its post office has. It was originally called Coretta, which was the name of a railway switch not far away. In 1900, the post office was redesignated as Rex, and in 1911 it became North Muskogee. Subsequently, the town was also sometimes called Falls City, apparently a reference to the falls or rapids of the nearby Verdigris River. The present name was finally settled on in 1919, bestowed in recognition of the O.K. 3-Ton Truck and Trailer, which was manufactured there by Oklahoma Auto Manufacturing Company.

34. Old Fig Garden, California

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 5,495

In 1912, a real estate developer from Kansas, J.C. Forkner, established what he hoped would become the world’s largest fig ranch on a plot of barren land near Fresno. He dubbed it Fig Garden. Forkner went bankrupt during the Depression and never realized his dream. In 1947, a group belonging to the local men’s club won nonprofit corporate status to “promote the general welfare” of the property, by then known as Forkner-Giffen Fig Garden Estates #1. The community is now completely surrounded by the city of Fresno.

[in-text-ad-2]

35. Parachute, Colorado

> Municipal status: Town

> Population: 1,181

Parachute was so named, it is said, either for the shape of an adjacent creek (called Parachute Creek) or because hunters on the cliffs above the site used to say they need a parachute to get down there.

36. Parole, Maryland

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 16,679

This Annapolis community was so named because during the Civil War it was the site of so-called Camp Parole. This was a tent city housing thousands of Union soldiers captured by the Confederates and returned to the Union army, where they waited return to service or be sent home.

[in-text-ad]

37. Peculiar, Missouri

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 4,856

This is one of many naming stories that has to do with what was then the U.S. Post Office Department. According to an account written in 1899, the citizenry applied for a post office to be established in their community. They suggested the name Excelsior, but were told that there was already an Excelsior elsewhere in Missouri. They tried again with other names and received the same reply. Frustrated, they asked the department to give them some “peculiar” name (writing the word in quotation marks). Back came a commission calling the post office exactly that, with no further explanation.

38. Pillow, Pennsylvania

> Municipal status: Borough

> Population: 270

The borough of Pillow was founded in 1818 by land developer John Snyder. Curiously, it was originally called Schneidershtettle — apparently a Germanicized version of his name, attached to a version of the Yiddish word for a small Jewish village. In 1864, it was incorporated as Uniontown, but as there was another Uniontown in the state, the post office was renamed Pillow, and the town officially took the name in 1965. According to the Pillow Historical Society, this was apparently in honor of the infamous Brigadier General Gideon Johnson Pillow, who was nearly court-martialed for taking false credit for victories in the Mexican-American War, and later, as a Confederate officer during the Civil War, was accused of hiding behind a tree during an important battle. His connection to Pennsylvania is not clear.

39. Pinch, West Virginia

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 2,826

According to an account from 1945, Pinch was named for a creek called Pinch Gut. Gut is a synonym for creek, but there may have been a play on words involved here. According to one account, “white men, hunting here in pioneer times, were attacked by Indians; and so long were they besieged that they almost starved…” Thus, their guts were pinched.

[in-text-ad-2]

40. Ship Bottom, New Jersey

> Municipal status: Borough

> Population: 880

This town on the Garden State’s Long Beach Island, incorporated in 1925, owes its name to an incident that took place offshore in 1817. According to local historian John Bailey Lloyd, a schooner piloted by one Stephen Willets came upon a ship that had overturned on the shoals. One of the schooner’s crew heard somebody tapping inside the upturned hull, and Willets chopped a hole in it with an axe, rescuing a young woman who had been trapped inside. The name of the wrecked ship was never discovered, but the locality was dubbed Ship Bottom. In 1925, the community joined with four neighboring towns to form the borough of Ship Bottom-Beach Arlington. In 1947, the second part of the name was dropped.

41. Smock, Pennsylvania

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 599

This long-time coal-mining settlement was named not for an apron or cover but for one Samuel Smock. A land speculator, farmer, and blacksmith, he bought a farmhouse and 190 acres of land here in 1869, later selling most of the property to coal companies. When a line of the Pennsylvania Railroad wanted to run tracks through the portion he still owned, he agreed, on the condition that the railway station be named for him. Smock Station later gave its name to the village.

[in-text-ad]

42. Tea, South Dakota

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 4,628

This city near Sioux Falls was originally called Byron. When locals submitted an application for a post office in the late 18th century, they were told by postal authorities that the name had been taken and were asked to submit 10 alternatives. At a meeting around the pot-bellied stove at Heeren’s and Peter’s General Store, townspeople came up with nine names and couldn’t think of a 10th. When somebody suggested that they take a tea break, they decided to write in “Tea” as the final alternative. That, of course, is the one the Post Office Department chose.

43. Thor, Iowa

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 183

No superheroes here. Thor was established in 1881 by the Western Town Lot Company, a division of the Chicago North Western Railway Company, which named it for the Norse god of thunder. Though Thor was a warrior god famed for slaying giants with his hammer, he was also, by virtue of his association with thunder and thus of rain, thought to aid in the growing of crops. This was the explanation for his appeal to this farming community.

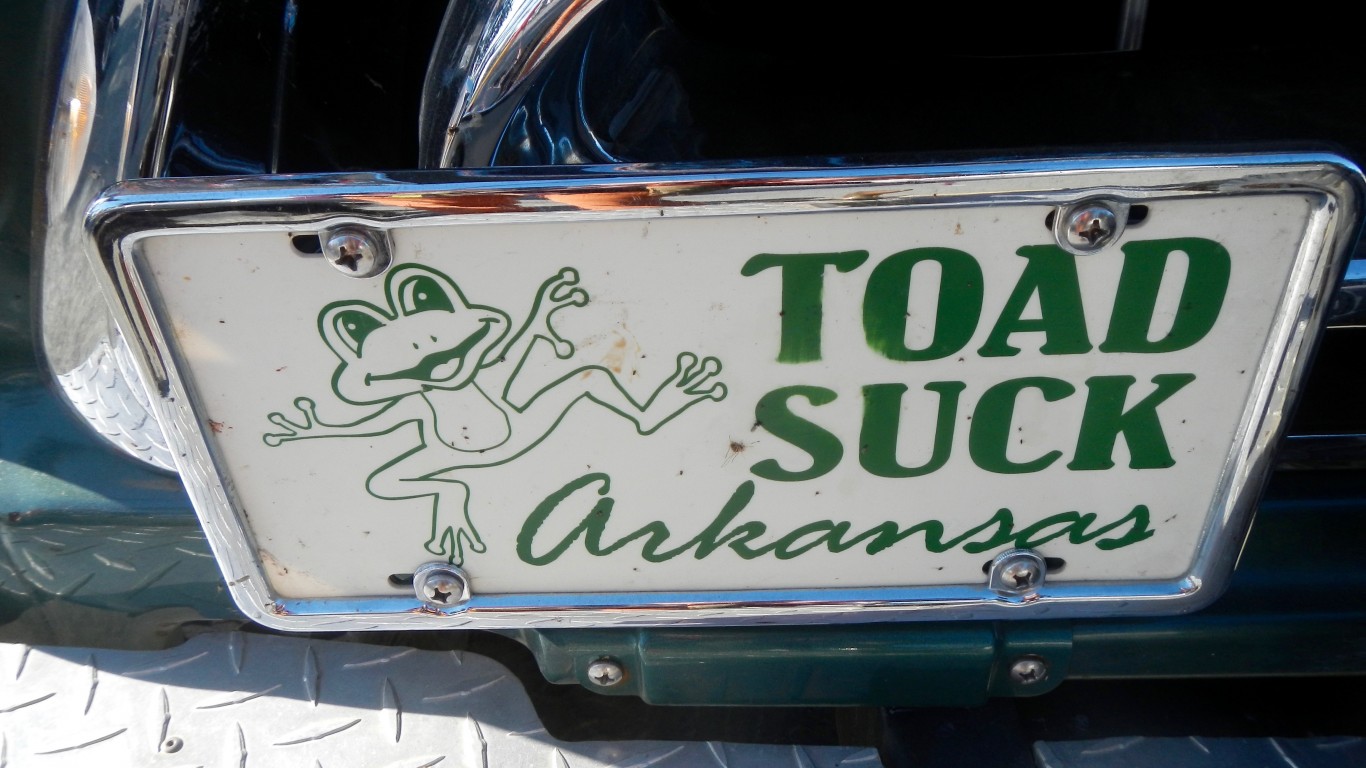

44. Toad Suck, Arkansas

> Municipal status: Unincorporated

> Population: 3,300 (est.)

According to the Toad Suck website, this is the origin of the community’s name: Steamboats used to ply the Arkansas River, but when it temporarily grew too shallow, they’d tie up near a local tavern to await for passable conditions. Their crews apparently imbibed so freely that somebody cracked, “They suck on the bottle ‘til they swell up like toads.”

[in-text-ad-2]

45. Truth or Consequences, New Mexico

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 6,157

This spa city southwest of Albuquerque used to be called Hot Springs. In 1950, though, radio host Ralph Edwards, of the popular quiz program “Truth or Consequences,” had the idea of finding a town somewhere in America that would change its name to honor the show in celebration of its 10th anniversary. The New Mexico State Tourist Bureau heard of the idea and passed it along to the Hot Springs Chamber of Commerce. The city held an election to decide the matter and voted to become Truth or Consequences.

46. War, West Virginia

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 1,044

War takes its name from War Creek, which in turn was named by local Indians for a battle that apparently occurred near its headwaters in 1788. Formerly called Miner’s City, War was incorporated under that name in 1920.

[in-text-ad]

47. What Cheer, Iowa

> Municipal status: City

> Population: 729

There are several theories as to the origin of this city’s name. An account of railway-connected place names published in 1908 attributes it to a Scottish miner who discovered coal in the area and exclaimed “What cheer!” — an old English expression. Another possibility is that a 19th century store owner in what was then called Petersburg, knowing the expression, simply thought it would be a good name for the town’s first post office.

48. Why, Arizona

> Municipal status: Census designated place

> Population: 162

This town probably got its name from the simple fact that it was near the Y-shaped junction of two state highways. According to one of the community’s early settlers, though, it was inspired by people driving through who asked, “Why are you living way out here?”

49. Whynot, North Carolina

> Municipal status: Unincorporated

> Population: 228

Whynot was founded in the 18th century by English and German immigrants. The story is that there was a long discussion about what to call the community, and finally somebody asked “Why not name it Why Not and then we can go home?”

[in-text-ad-2]

50. I.X.L, Oklahoma

> Municipal status: Town

> Population: 51

According to the town website and the Oklahoma Historical Society, there are many theories as to the meaning of I.X.L. (or simply IXL). Some people think it’s an onomatopoeic boast suggesting “I excel.” Others believe it to be a Roman numeral (though the letters are in the wrong order for that). The website ends up deciding that, because the town was built on a piece of former Cherokee land, its initials signify Indian Exchange Land. The Oklahoma Historical Society, however, points out that the surrounding towns were at that time predominately African American, and adds, without further explanation, that “IXL was the name used to describe a widely dispersed African American community.”

In order to identify the 50 strangest town names in America, 24/7 Wall St. reviewed the nearly 30,000 names of cities, towns, villages, boroughs, and CDPs (census-designated places — settled but unincorporated population centers as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau), collected by the U.S. American Community Survey. We then used our best judgment to identify the most unusual among them.

To help narrow our search, we used four criteria. The first group comprises towns with names that occur only once in the United States and do not consist of discrete words in the English language. For example, Ho-Ho-Kus, New Jersey, is both the only town with that name and a word (or series of words) not found in the dictionary.

The second group is composed of town and place names that are discrete words not expected to be used as town names. For example, the strangeness of the name of Pillow, a town in Pennsylvania, comes not because there’s anything strange about the word “pillow,” but from the unusual choice of using a common noun (though it turns out that it isn’t in this case) to designate a place.

The third and fourth groups consist of names with four or fewer characters as well as names with 20 or more characters as both would likely include examples outside of mainstream naming conventions.

Finally, we used informal sources to add a small number of small unincorporated communities not classed as CDPs, just because they had names (and stories behind those names) that seemed too good to miss.

Start by taking a quick retirement quiz from SmartAsset that will match you with up to 3 financial advisors that serve your area and beyond in 5 minutes, or less.

Each advisor has been vetted by SmartAsset and is held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests.

Here’s how it works:

1. Answer SmartAsset advisor match quiz

2. Review your pre-screened matches at your leisure. Check out the advisors’ profiles.

3. Speak with advisors at no cost to you. Have an introductory call on the phone or introduction in person and choose whom to work with in the future

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.