Special Report

Cool and Creepy Halloween Traditions Around the World

Published:

Last Updated:

We associate Halloween, which marks the start of the fall and winter holiday season, with trick-or-treating, costume parties, and jack-o’-lanterns. It has considerably more serious origins, though.

Halloween evolved from an old Celtic holiday, Samhain, marking the end of summer, a day on which the gods or spirits would appear on Earth to play tricks on mortals. When Christianity came to Britain, the Church adopted elements of the holiday, combining it with two existing holy days, All Saints’ Day (Nov. 1), commemorating all the Christian saints, and All Souls’ Day (Nov. 2), an occasion for honoring the dead.

“Hallow” was an old word for saint, and Oct. 31, the eve of All Saints’ Day, was originally called All-Hallow-Even (short for evening). This evolved into “Hallowe’en,” and then into Halloween.

The Halloween traditions we’re most familiar with — including jack-o’-lanterns and dressing in costumes to confuse the wandering spirits — came to America with Irish immigrants in the 19th century. Americans, in turn, have exported these traditions to much of the world, so that the day is celebrated U.S.-style today in places as diverse as China, Egypt, and South Africa.

Many cultures have their own autumn holidays celebrating the dead. In Cambodia, it’s Pchum Ben, a three-day period in September or October during which the gates of hell are said to open, letting the spirits out to receive food offerings from their relatives. Bolivians observe the Fiesta de las Ñatitas on Nov. 8 each year by decorating skulls — real ones, either from deceased family members or obtained from medical schools or old cemeteries — with flowers, jewelry, hats, and glasses.

Many other countries observe Oct. 31, and/or All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day, with customs of their own, usually involving some kind of tribute to their departed family and friends.

Click here for cool and creepy Halloween traditions around the world.

Austrian Catholics celebrate the days between Oct. 30 and Nov. 8 as Seleenwoche, or All Souls’ Week. On the night of the 31st, an old practice was to leave bread and water out on a table, and light a lamp, to welcome and nourish the souls of the dead.

[in-text-ad]

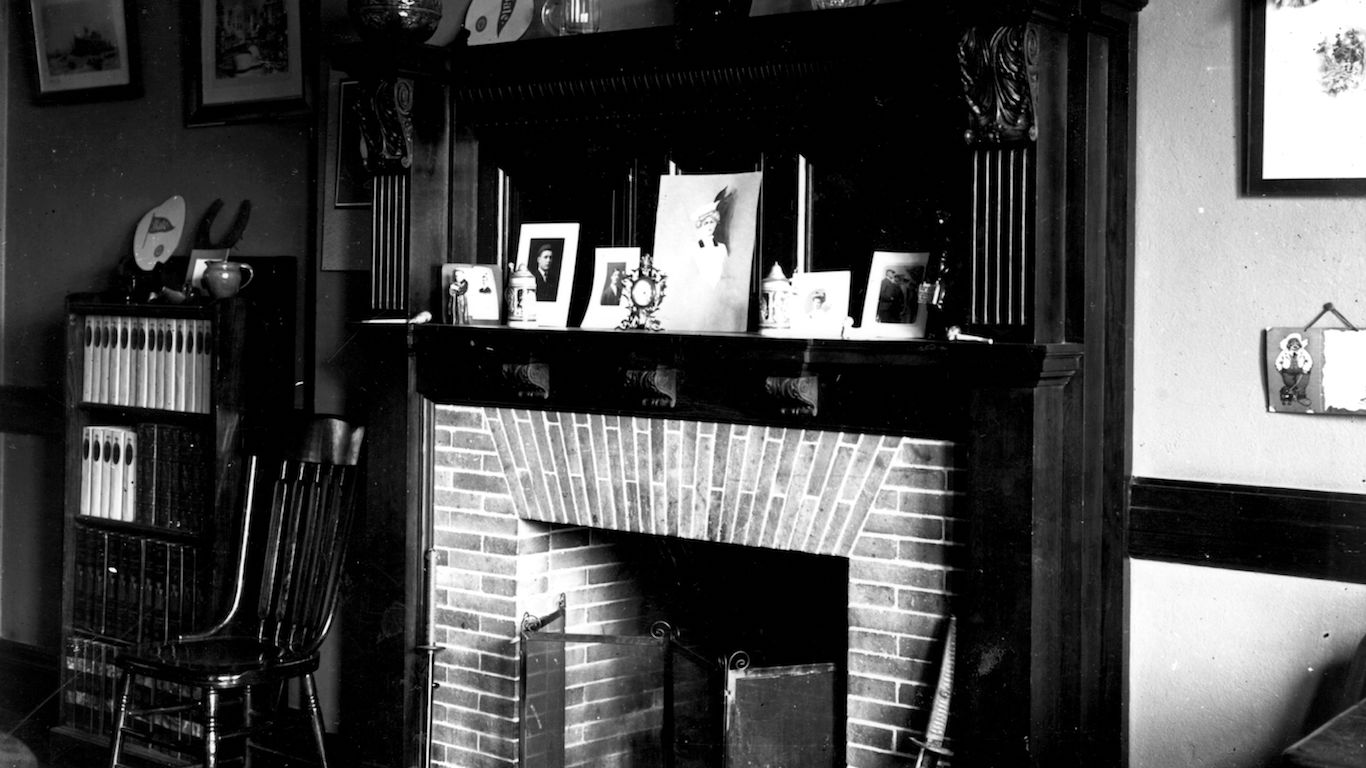

One old Czech custom is to place chairs around the fireplace on All Souls’ Day, Nov. 2, one for each living family member and one for each departed one. People also visit the graves of the departed and adorn them with flowers and candles.

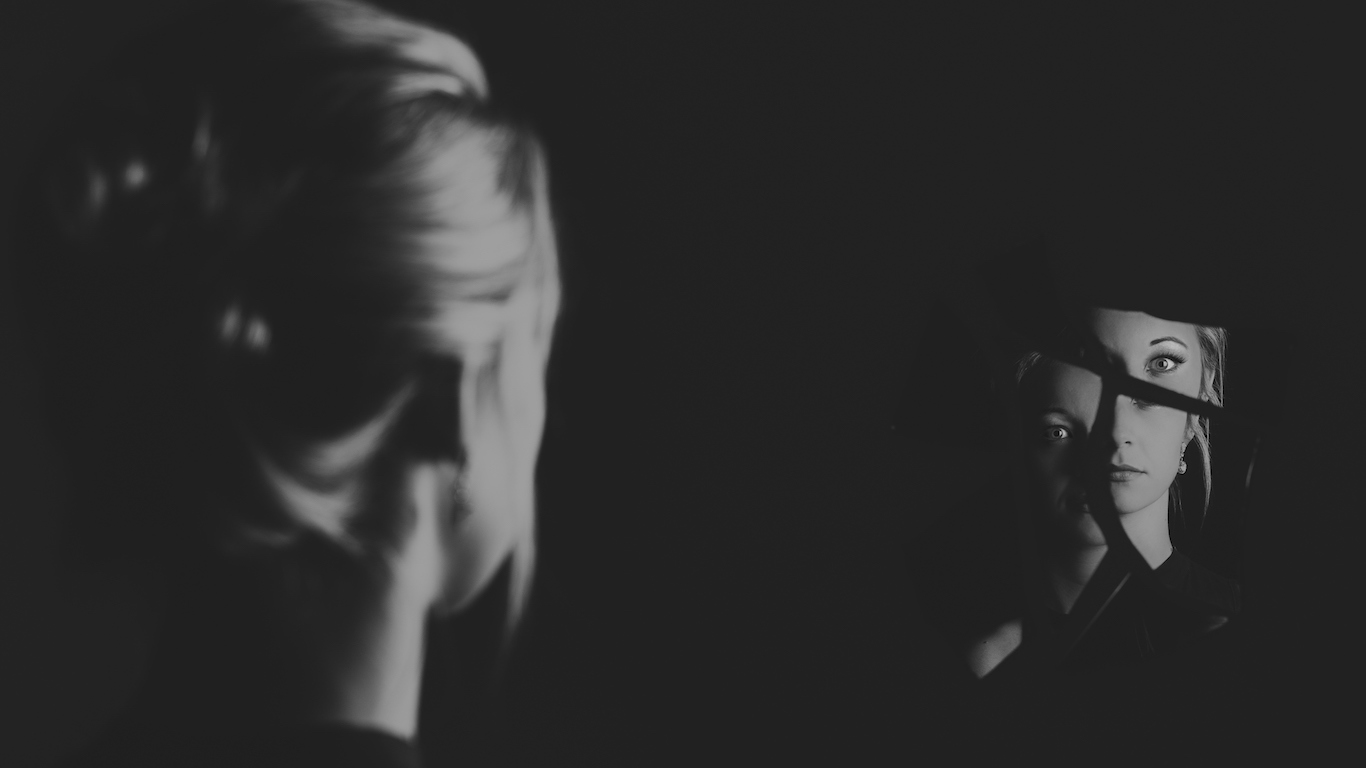

In England and elsewhere in the U.K., there’s a superstition that a man or woman staring into a mirror in a dark room on Halloween will see the face of his or her future mate in the background. If instead of a face the image is of a skull, the person looking would die before marrying. Britain’s Guy Fawkes Day on Nov. 4 is often seen as a parallel celebration to Halloween, with bonfires and — in earlier times, at least — children crying “A penny for the Guy!” instead of “Trick or treat.” This day isn’t connected with liturgical observance, however. It commemorates the foiling of a mass political assassination plot.

Some Germans hide all their knives between Oct. 30 and Nov. 8, but especially on Halloween night, so that the spirits of the dead, believed to reappear during that period, wouldn’t accidentally cut themselves.

[in-text-ad-2]

As in other countries, people in Haiti honor the deceased each fall by dressing in costumes, visiting graveyards, and offering food to the dead. During this Caribbean nation’s annual Fet Gede, or Feast of the Dead, held annually on Nov. 1 or 2 (or both), adherents of vodou (voodoo) who believe they are possessed by the Gede Lwa — spirits of the dead — also pay homage to Baron (or Bawon) Samedi, father of the spirits of the dead. They dance wildly in the streets and drink — or even wash themselves with — raw rum spiked with very hot chiles. It is said that those who are faking possession will burn themselves, while the genuinely possessed are immune to the spice.

Barmbrack (bairín breac in Irish) — literally “speckled loaf”— is a dense fruitcake made with raisins, currants, and candied citrus peel. On Halloween, in earlier times, bakers hid a ring, a piece of cloth, and a stick inside each barmbrack. When the cake was sliced and served, it was said that whoever got the ring would marry, whoever got the cloth would enter the clergy, and whoever got the stick would remain single (some barmbracks also included a coin, which signified forthcoming wealth). Health laws now prohibit the inclusion of anything but the ring in commercial barmbrack, but the fruitcake is still widely eaten on the holiday. Ireland has many other ways of celebrating the holiday, among them carving turnips jack-o’-lantern style, sprinkling holy water on farm animals to ward off evil spirits, and leaving a perfect ivy leaf in a cup of water overnight. If the leaf remains unblemished in the morning, the person who placed it there is supposedly assured a year of good health.

[in-text-ad]

In place of All Saints’ and All Souls’ days, Mexico and (increasingly) other Latin American countries celebrate a two-day “Día de Los Muertos,” or the Day of the Dead, on Nov. 1-2. The first day is dedicated to deceased children, called “angelitos,” or little angels; the second is the Day of the Dead proper. One important activity is the building of temporary altars in cemeteries and sometimes at home as tributes to the departed. These are adorned with candy and other confections, including skulls made of sugar, bottles of tequila or other liquors for adults, toys for children, and objects of significance to the dead, as well as marigolds — said to attract the spirits to their offerings. Calacas — colorfully dressed comical skeletons and skeleton masks — are seen everywhere. People also eat pan de muerto, bread of the dead, an orange-scented sweet bread decorated with “bones” made from the same dough, often while they’re visiting graves.

Though the practice is dying out and today observed mostly in the rural provinces, Pangangaluluwa — the Filipino equivalent of Halloween — was once celebrated on Oct. 31. The celebration involves groups of people going house to house after having visited the graves of loved ones, singing songs, and asking for prayers and donations (to be turned over to the local church).

Two old Scottish Halloween traditions involve food. On the holiday, young women peel an apple in one long piece and throw it over their left shoulders with their right hand. The way it lands is said to form the initial of their husband-to-be’s first name. The other tradition is to place two hazelnuts side by side in the fire, representing the one who placed them and his or her intended. The lore says that if they catch fire and burn silently together, the two will be married. If they burn hot and jump apart, they’ll have a fight and separate.

[in-text-ad-2]

In Spain’s Catalonia region, Oct. 31 is celebrated as La Castanyada, or the chestnut festival, an observance tied to All Saints’ Day. The tradition on this occasion is for families and friends to meet and eat roasted chestnuts, sweet potatoes, and panellets — sweet egg yolk and almond pastries, typically covered in pine nuts — and drink sweet moscatel wine. There are several theories as to the origin of this celebration. Church bells used to ring all night on the eve of All Saints’ Day, and some say that the Castanyada foods were sustenance for the bell-ringers. It may simply be, however, that chestnuts were a convenient food left to roast while people said prayers for their dead relatives.

The thought of burdening your family with a financial disaster is most Americans’ nightmare. However, recent studies show that over 100 million Americans still don’t have proper life insurance in the event they pass away.

Life insurance can bring peace of mind – ensuring your loved ones are safeguarded against unforeseen expenses and debts. With premiums often lower than expected and a variety of plans tailored to different life stages and health conditions, securing a policy is more accessible than ever.

A quick, no-obligation quote can provide valuable insight into what’s available and what might best suit your family’s needs. Life insurance is a simple step you can take today to help secure peace of mind for your loved ones tomorrow.

Click here to learn how to get a quote in just a few minutes.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.