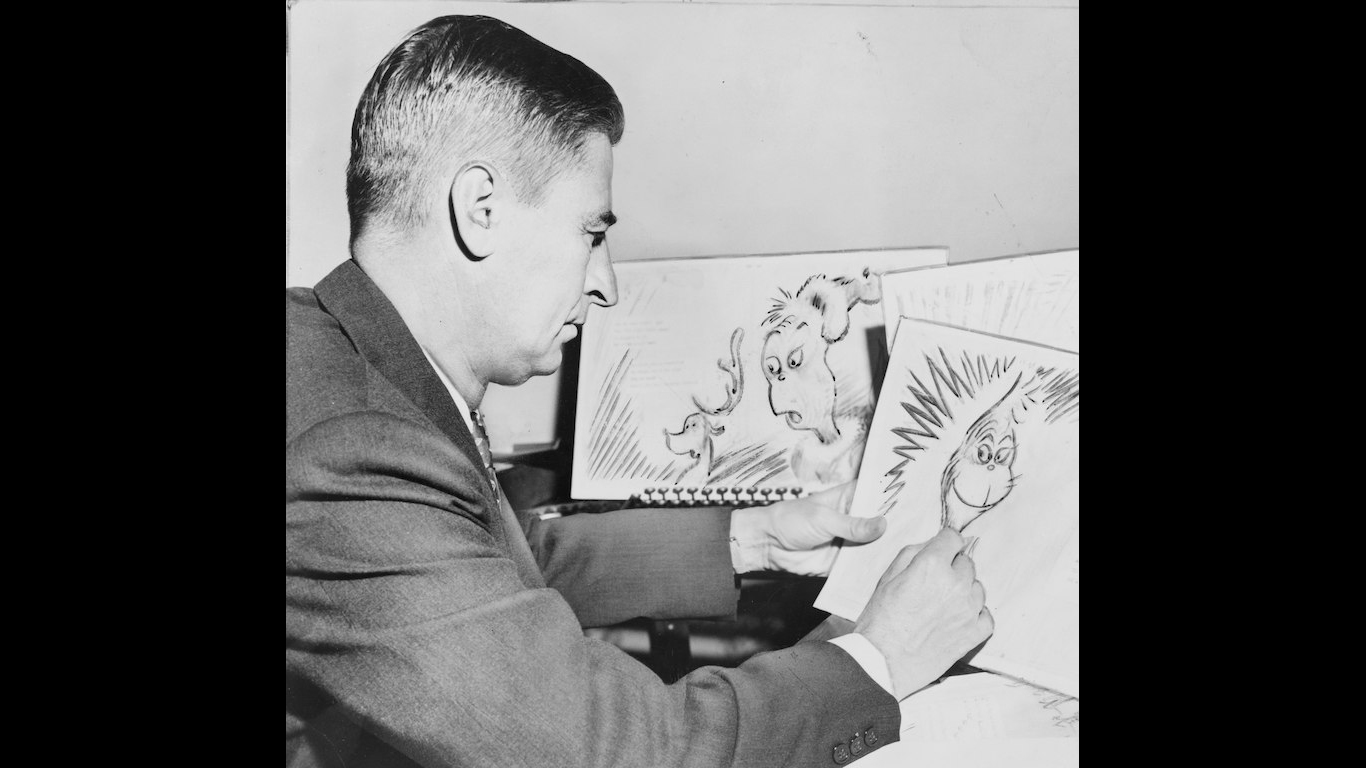

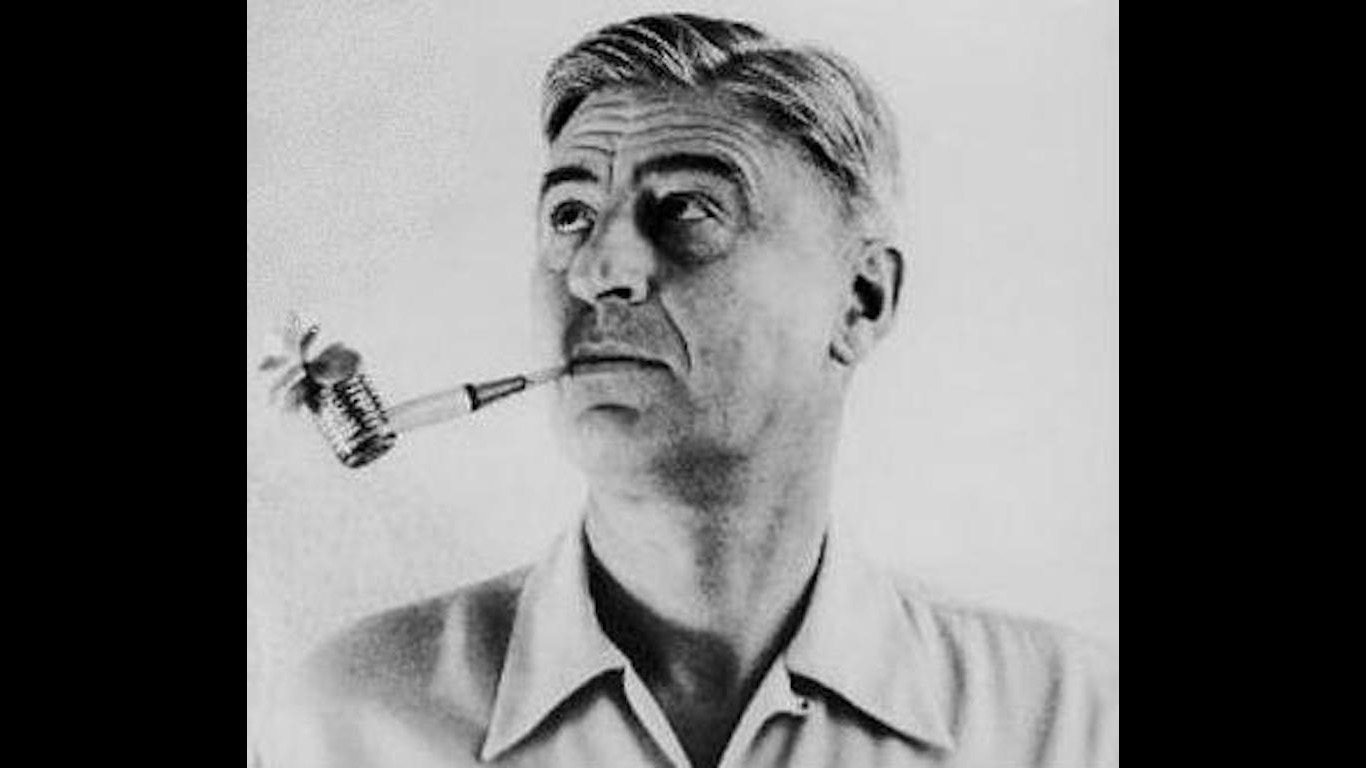

Theodor Seuss Geisel, who was called Ted as a boy but would one day be known to the world as Dr. Seuss, was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1904. His father, Theodor Robert Geisel, who co-owned a brewery, often took young Ted to the city zoo. Perhaps inspired by these visits, Ted — with the encouragement of his mother, Henrietta Seuss — drew animal caricatures on his bedroom walls.

In 1921, along with 16 fellow graduates of Springfield’s Central High School, Geisel enrolled at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. He was immediately attracted to the college humor magazine, “Jack-o-Lantern,” and began contributing stories and cartoons to it, becoming its editor-in-chief in his junior year. It was in the magazine’s pages that he first used the pseudonym “Seuss,” after an infraction of the law got him deposed as editor.

Geisel went on to a career in advertising in New York city, creating illustrations for an insect spray and other products. His first appearance between hard covers came in 1931: a series of illustrations for a book called “Boners,” filled with unintentionally funny excerpts from school tests and term papers. The first Dr. Seuss book, “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street,” came six years later.

Click here for 30 things you didn’t know about Dr. Seuss.

Dr. Seuss produced some 66 books in all, counting those he wrote but didn’t illustrate, those he co-authored or wrote under a pseudonym, and those that were published posthumously. He is the world’s best-selling children’s author, and according to some sources either the ninth or 11th most popular fiction writer of any kind in history, beating out Stephen King, Leo Tolstoy, and many other famous authors of past and present. His books, which have been translated into 30 languages, have sold somewhere between 500 million and 650 million copies.

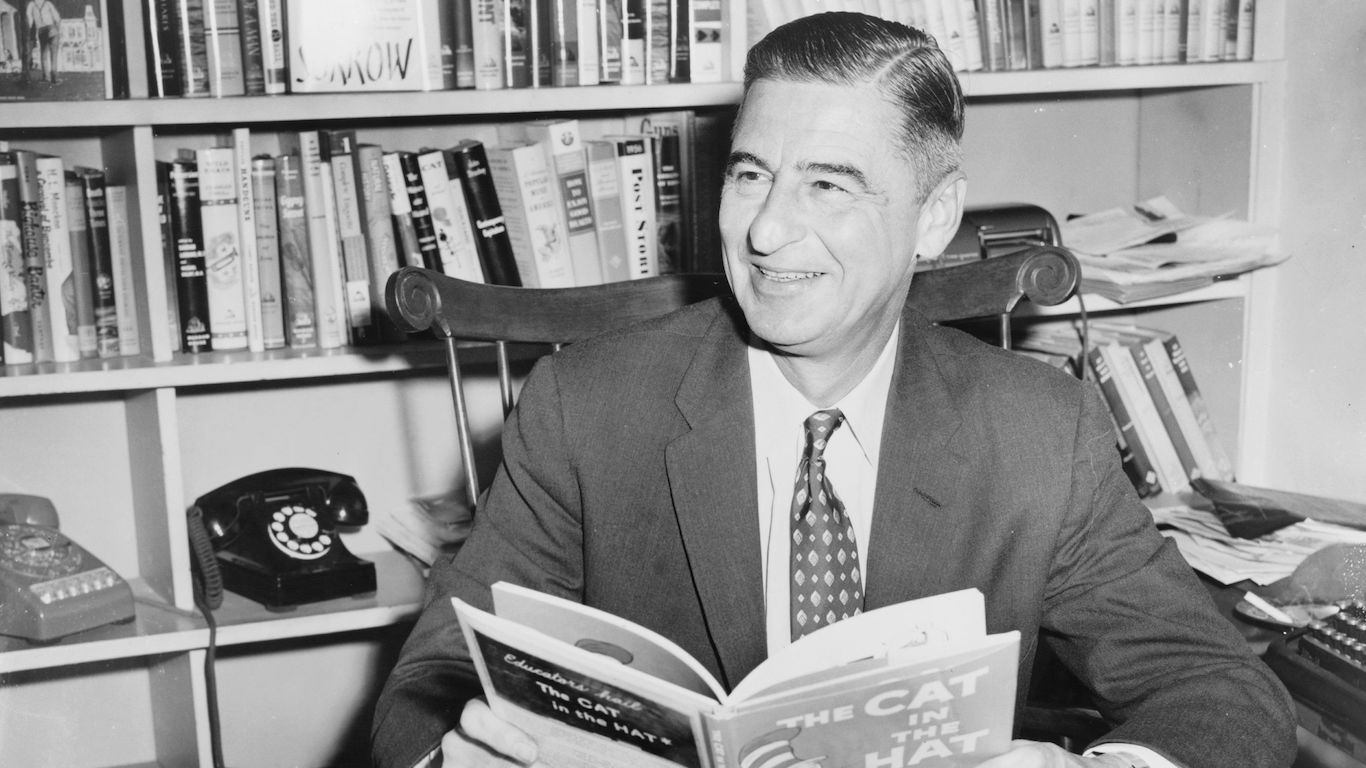

The book that made Dr. Seuss a star was his 13th, “The Cat in the Hat,” published in 1957. It came about as a reaction to an article in LIFE magazine bemoaning the state of children’s reading levels in America. Geisel’s publisher asked him to write a book using only 220 basic vocabulary words so it could be used as a children’s reader. “The Cat in the Hat” was the result (he actually used 236 words, but nobody complained), and it became a hit immediately.

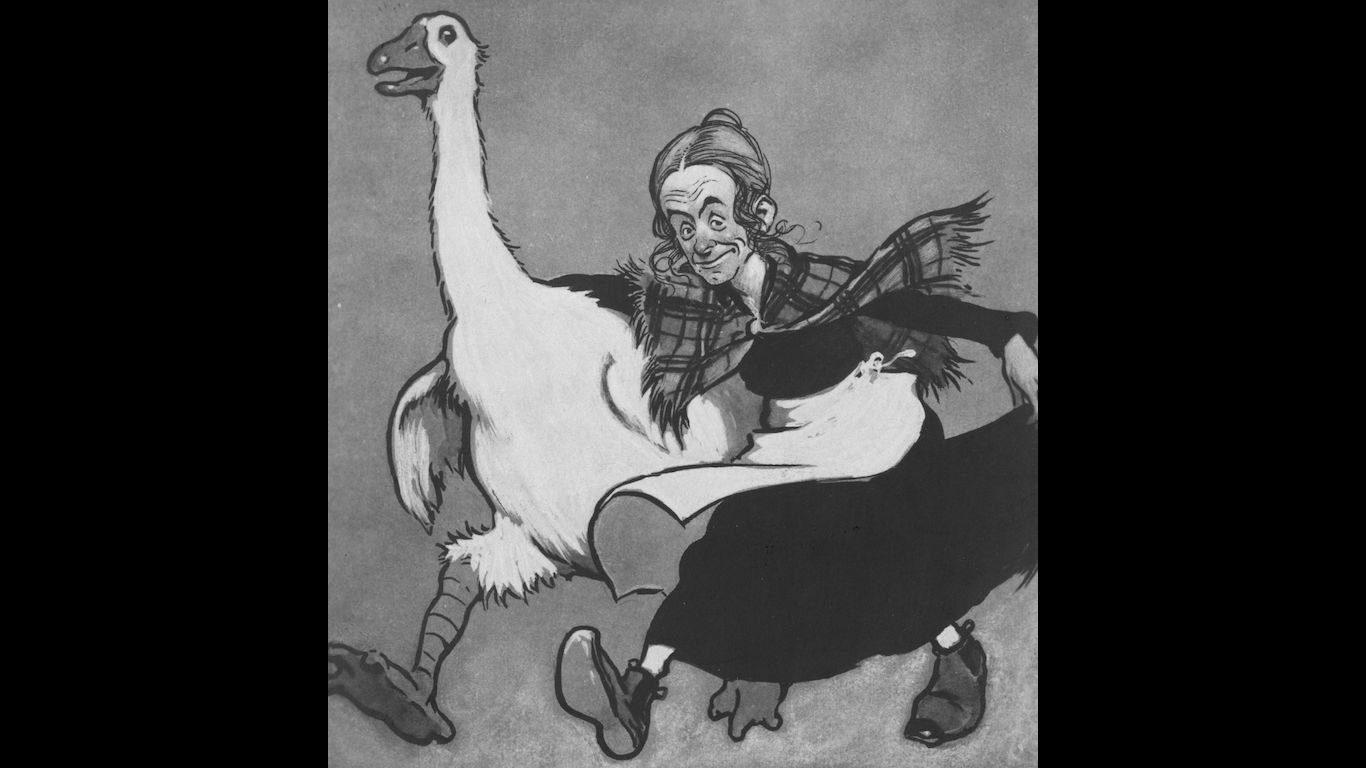

The book’s success inspired him and his publisher to launch a whole series of Beginner Books, written by Dr. Seuss and others. In the early 1950s, he had also started to produce books with allegorical social or political messages. For instance, “Horton Hears a Who!” stands against prejudice; “Yertle the Turtle” is about the overthrow of a dictatorial turtle said to have been based on Adolf Hitler; “The Sneetches” opposes anti-Semitism. Later, he also published “The Lorax,” a plea for environmental conservation, and “The Butter Battle Book,” which tackles the theme of nuclear disarmament.

Variously hailed as the American Poet Laureate of Nonsense and the Modern Mother Goose, Dr. Seuss has brought pleasure to (and encouraged reading comprehension in) four generations of children around the world. But not everything about him was family-friendly. 24/7 Wall St. has uncovered some surprising facts about this prolific author and illustrator.

Methodology

To unearth little-known facts about Theodor “Dr. Seuss” Geisel, 24/7 Wall St. consulted the Springfield Museums’ Seuss in Springfield website, Penguin Random House’s Seussville website, the website of the New England Historical Society, an article reproducing early Seuss cartoons on Buzzfeed, and the following books: “Dr. Seuss: The Cat Behind the Hat” by Caroline M. Smith; “Of Sneetches and Whos and the Good Dr. Seuss,” edited by Thomas Fensch; “Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: A Biography” by Judith & Neil Morgan; “Theodor Geisel: A Portrait of the Man Who Became Dr. Seuss” by Donald E. Pease; “Who Was Dr. Seuss?” by Janet B. Pascal; and “The Beginnings of Dr. Seuss: An Informal Reminiscence,” edited by Edward Connery Lathem.

1. His grandfather was a partner in the Kalmbach & Geisel brewery, known familiarly as “Come Back and Guzzle,” which later morphed into the Springfield Brewing Company, one of the largest such operations in New England.

[in-text-ad]

2. Former President Theodore Roosevelt once humiliated him on stage, exclaiming “What’s this boy doing here?” instead of giving him the award for selling war bonds that he was expecting.

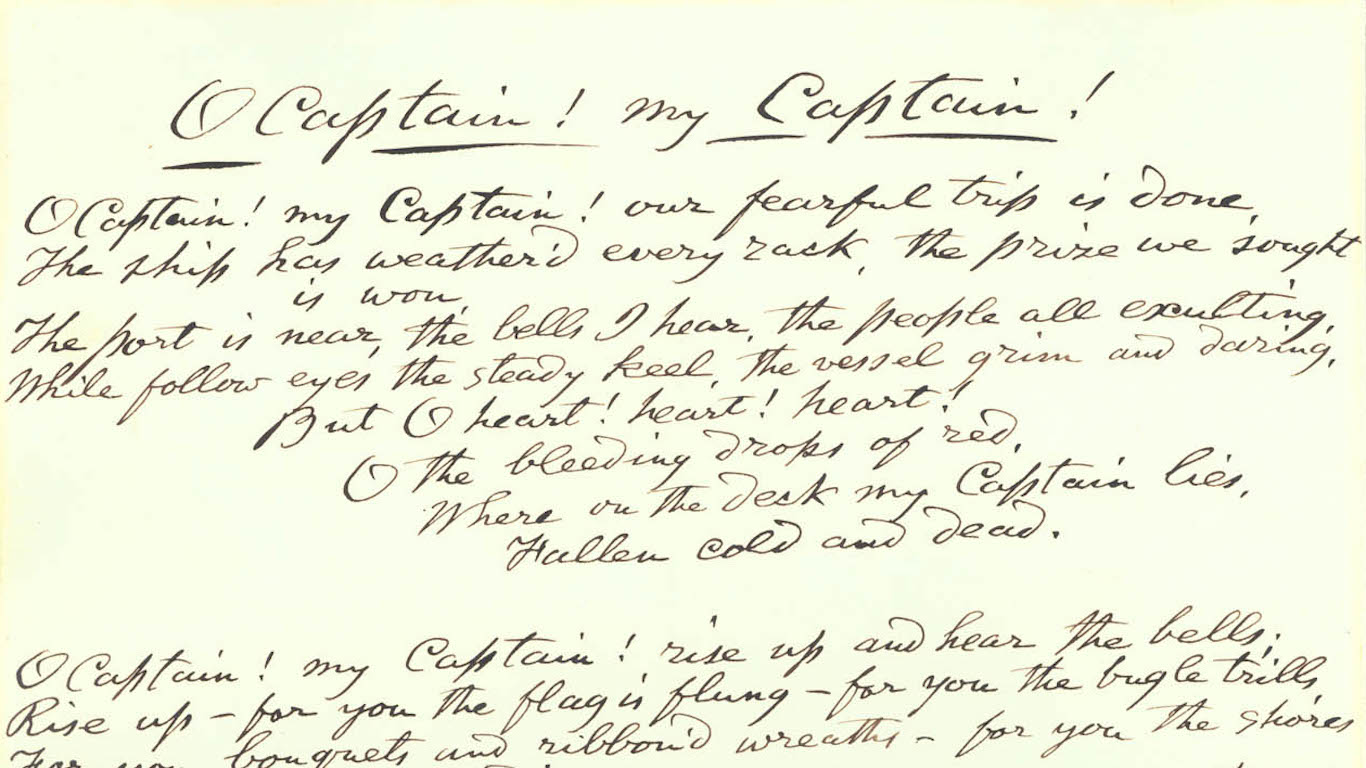

3. His first published work was a parody of Walt Whitman’s poem “O Captain! My Captain!,” composed as a plaint about the difficulty of Latin class for his high school newspaper.

4. He wrote a minstrel show called “Chicopee Surprised” as a fundraiser for a school trip, and he performed in it, in blackface.

[in-text-ad-2]

5. He was fired from the college humor magazine at Dartmouth College for drinking gin with friends in his dorm room — during Prohibition!

6. “Seuss” is pronounced “zoice” in German, but Geisel preferred to rhyme it with “Goose,” as in Mother Goose.

[in-text-ad]

7. He wasn’t really a doctor. He began using the honorific in an attempt to mollify his father, who had wanted him to study medicine.

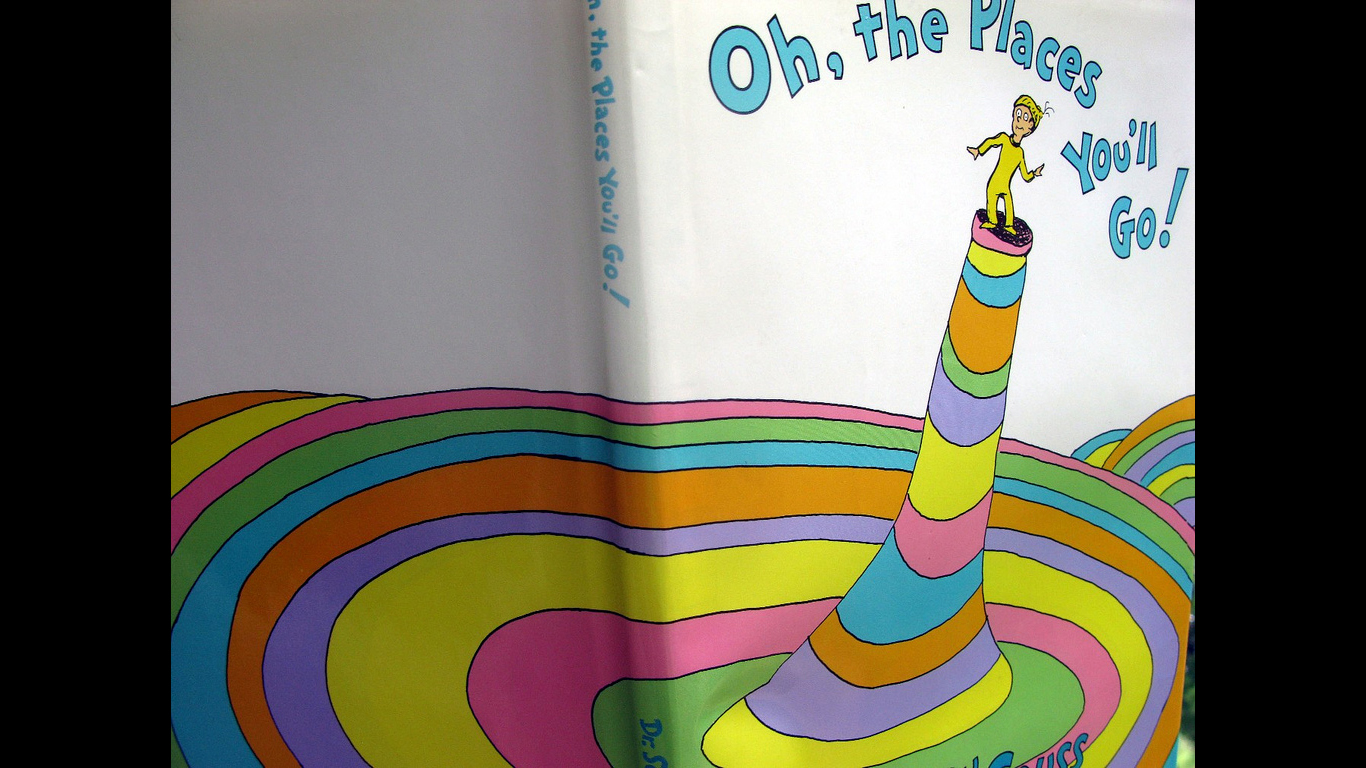

8. “Oh, the places you’ll go!”, which became the title of his last book (published in 1990), was a Dartmouth catchphrase in the 1920s.

9. He was voted “Least Likely to Succeed” by Casque & Gauntlet, the senior society to which he belonged.

[in-text-ad-2]

10. He attended Oxford University in 1926, pursuing a master’s degree in English, but he left after less than a year.

11. Helen Palmer, a fellow student at Oxford who was to become his first wife, encouraged him to give up the academic world to concentrate on his art.

[in-text-ad]

12. He and Helen were unable to have children, but he sometimes pretended humorously to have offsprings, with names like Chrysanthemum-Pearl, Wickersham, Miggles, and Boo-boo.

13. His first published cartoon appeared in a popular weekly magazine, “The Saturday Evening Post,” in 1927.

14. In 1929, he drew a four-panel cartoon for the satirical weekly Judge that included a blatantly racist image, complete with the n-word.

[in-text-ad-2]

15. When it ran into financial difficulties, Judge began paying him in merchandise, including 100 cartons of shaving cream on one occasion and 13 gross of nail clippers on another.

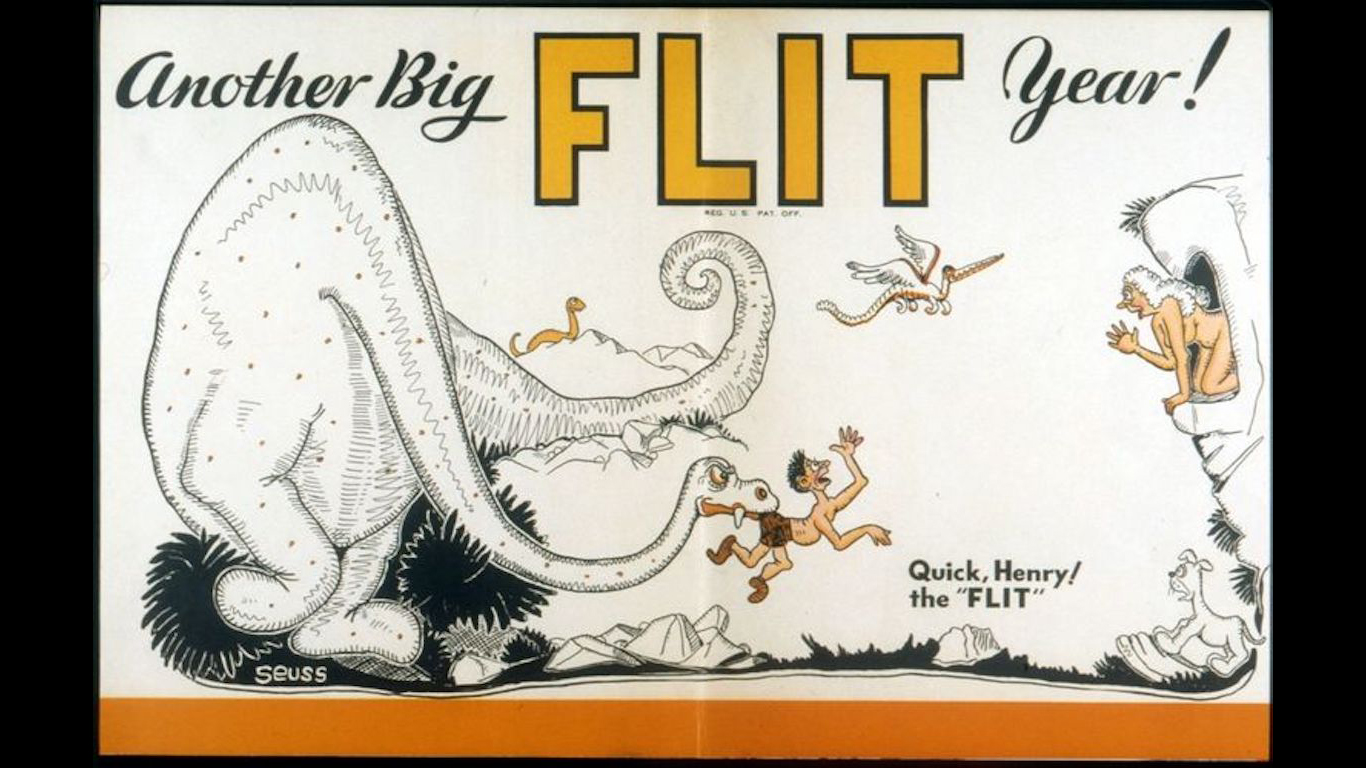

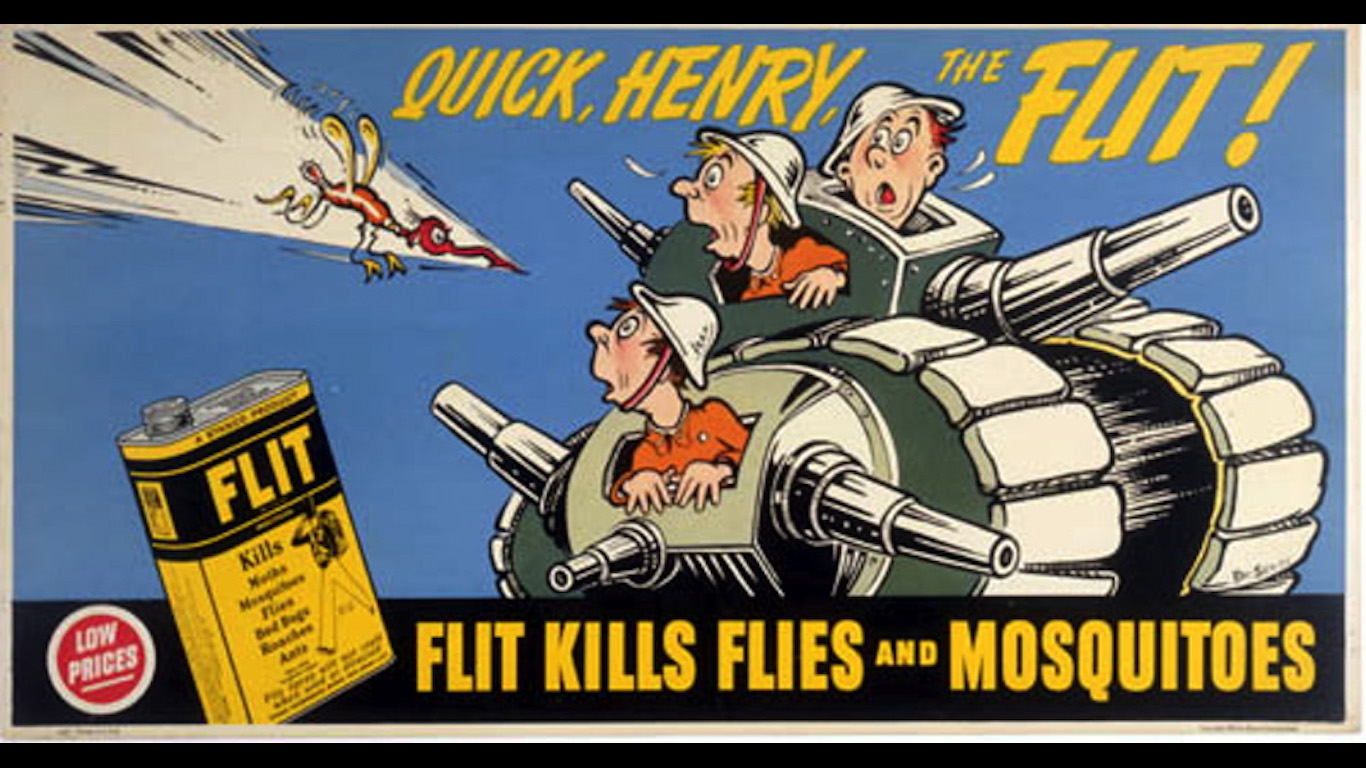

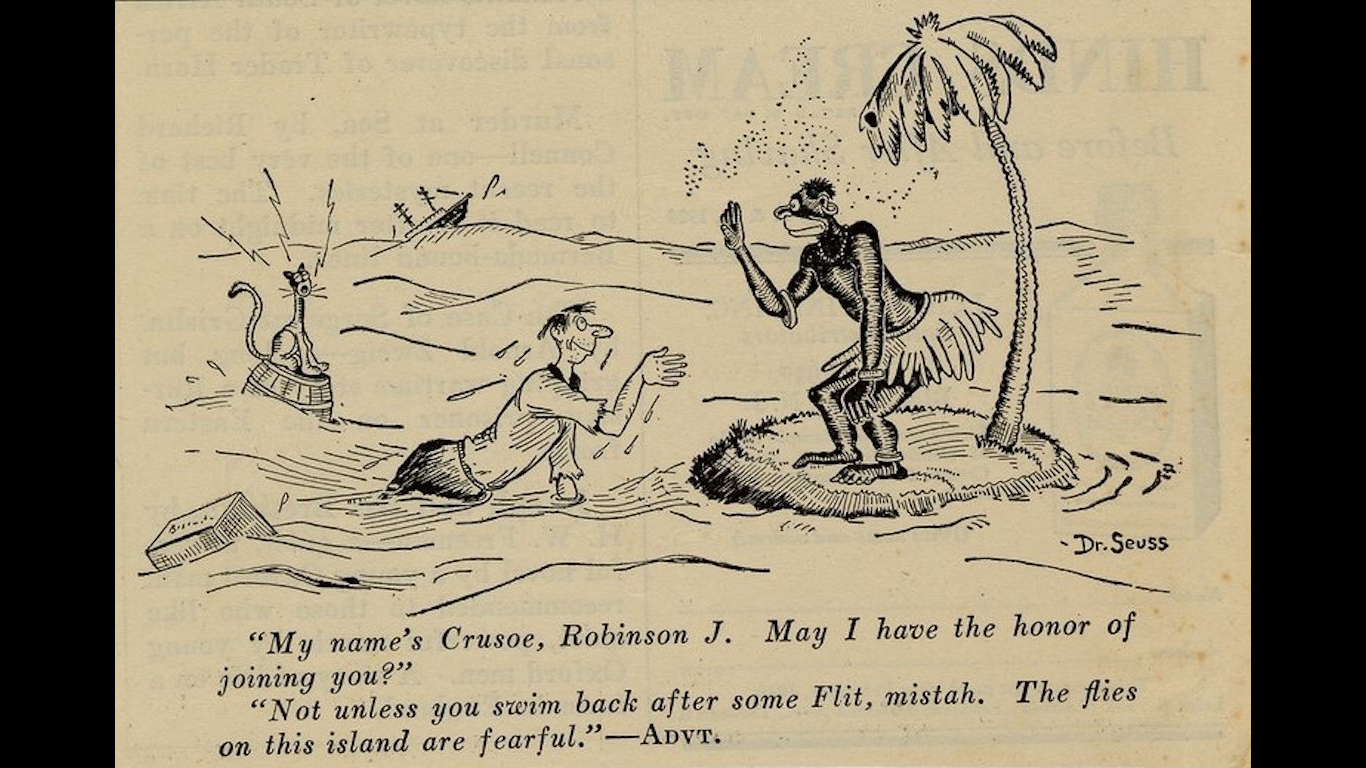

16. He was subsequently hired to create ads by the makers of Flit, a DDT-laced bug spray produced by a subsidiary of Standard Oil of New Jersey.

[in-text-ad]

17. He created a slogan for the bug spray — “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” — that became an oft-quoted slogan of the day ala “Where’s the Beef?” in later years.

18. Some of his Flit ads featured more racist imagery, of both blacks and Middle Easterners.

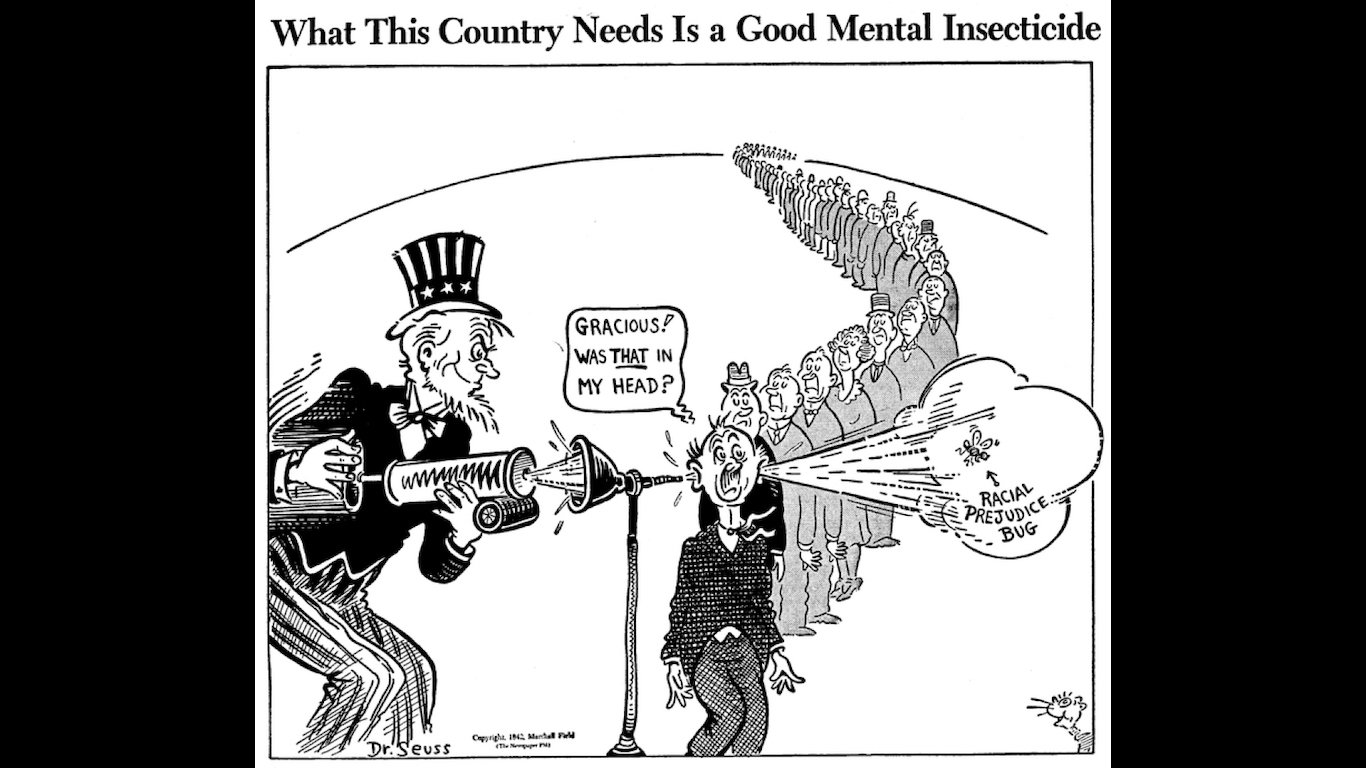

19. He later rejected racism, drawing cartoons such as one featuring Uncle Sam wielding a Flit-like spray to blow the “Racial Prejudice Bug” out of the heads of white citizens.

[in-text-ad-2]

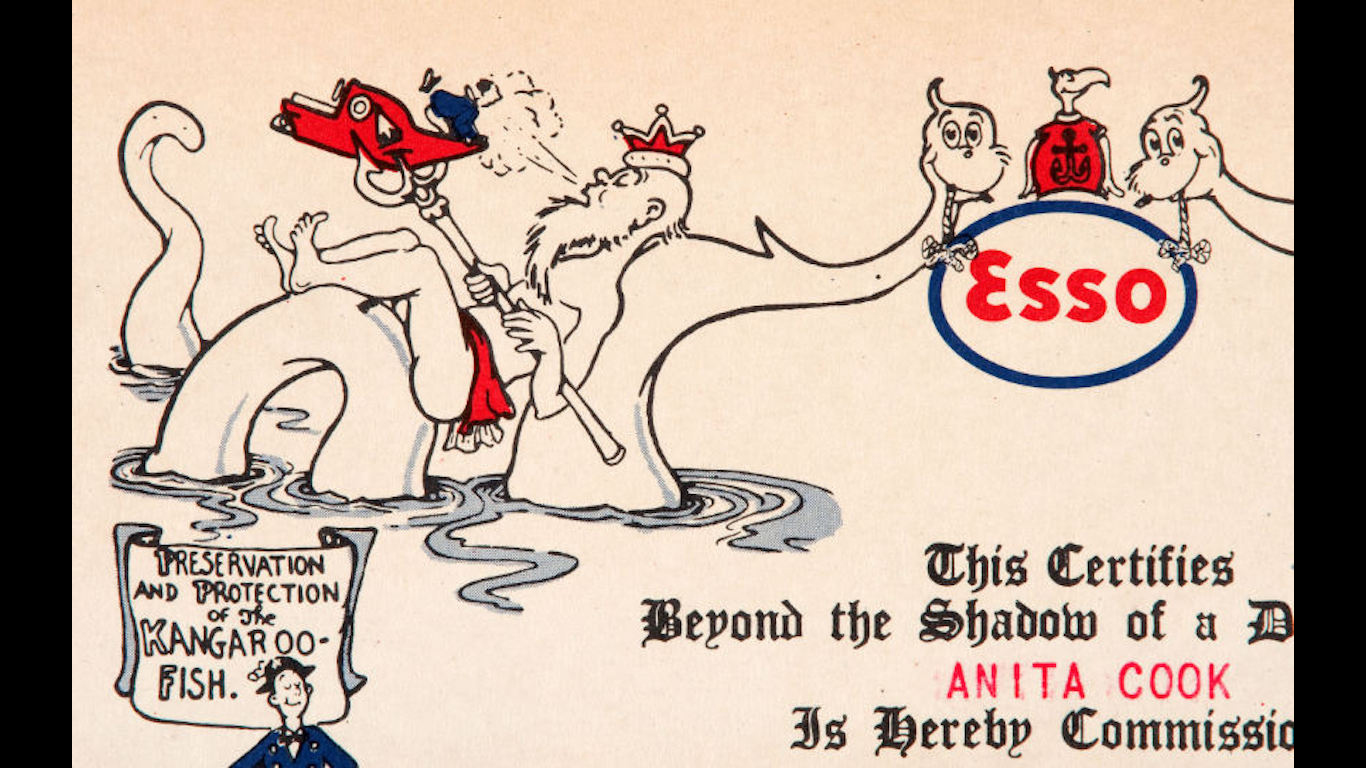

20. Working for another Standard Oil subsidiary, which produced Essomarine boat fuel, he became “Admiral-in-Chief” of the so-called Seuss Navy, an outfit made up for promotional purposes.

21. He began writing and drawing children’s books because it was one of the few genres not forbidden by his ad contracts.

[in-text-ad]

22. His first published children’s book, “And to Think That I Saw it on Mulberry Street,” was rejected by publishers 27 times before it went to press in 1937.

23. In 1939, he published a book for adults called “The Seven Lady Godivas,” full of cartoon nudes. It didn’t sell well, and he went back to children’s books.

24. During World War II, he enlisted in the army and co-wrote some 27 humorous instructional cartoons featuring a hapless army recruit called Private Snafu.

[in-text-ad-2]

25. He might have invented the word “nerd,” which appears in his 1950 book “If I Ran the Zoo” — though the derivation is disputed.

26. He wrote a fantasy movie about an evil piano teacher, “The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T.,” released in 1953.

[in-text-ad]

27. His first wife, Helen, who was in frail health, committed suicide after Geisel had an affair with a friend’s wife, Audrey Dimond — who was to become the second Mrs. Geisel.

28. He has a star on Hollywood Boulevard’s Walk of Fame in recognition of the fact that his stories have inspired three feature films and 11 TV specials.

29. His license plate read “GRINCH,” a reference to one of his most famous books, “How the Grinch Stole Christmas!”

[in-text-ad-2]

30. He was a heavy smoker until the early 1980s and died of oral cancer — though not until 1991, when he was 87.

It’s Your Money, Your Future—Own It (sponsor)

Are you ahead, or behind on retirement? For families with more than $500,000 saved for retirement, finding a financial advisor who puts your interest first can be the difference, and today it’s easier than ever. SmartAsset’s free tool matches you with up to three fiduciary financial advisors who serve your area in minutes. Each advisor has been carefully vetted and must act in your best interests. Start your search now.

If you’ve saved and built a substantial nest egg for you and your family, don’t delay; get started right here and help your retirement dreams become a retirement reality.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.