Women have been using the power of the march to have their voices heard, make politicians listen and change legislation, as well as to change public opinion of their value in society.

Following the 19th amendment, which gave women the right to vote in 1920, there was a second wave of feminism in the late 1960s and 1970s, and with it more marches. This time, the goals included fighting female oppression, rallying for reproductive rights and preventing violence against women.

Since then, women have continued to fight to have their voices heard, particularly in the face of elected officials whose policies they see as a threat to women’s and reproductive rights.

In honor of National Women’s History Month celebrated in the United States every year, 24/7 Wall St. compiled a list of 10 women’s marches that have shaped the country over the last century.

Click here to read about the marches that have shaped America.

Women’s Suffrage Parade, March 3, 1913, Washington, D.C.

The movement for women’s right to vote began in the late 19th century, but the first major mass demonstration didn’t occur until 1911. On the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration up to 8,000 suffragists walked down Pennsylvania Avenue and past the White House, along with over 20 parade floats, nine bands, and four mounted brigades.

Led by the National American Woman Suffrage Association and Alice Paul, who was inspired by the British suffrage movement just a few years earlier, the protestors had a permit and the constitutional right to protest. Yet they faced a crowd that opposed suffrage and were physically attacked. That actually resulted in bigger support for the movement. Suffragist protests continued in the following years, leading to the 19th amendment, which gave women the right to vote and was ratified in 1920.

[in-text-ad]

Miss America Protest, September 7, 1968, Atlantic City

The Miss America Protest in September 1968 may not have changed a pageant that only just gave up its swimsuit competition last year, but it is largely credited with ushering in the second wave of feminism, following the suffrage movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Started by radical feminist Carol Hanisch, a press release invited “women of every political persuasion” to “protest the image of Miss America, an image that oppresses women in every area in which it purports to represent us.” There was also opposition to the pageant’s racism for never having a black contestant or a “a true Miss America — an American Indian.”

A few hundred women protested on the Atlantic City boardwalk, just outside the pageant, with signs such as: “All Women Are Beautiful,” “Cattle parades are demeaning to human beings,” and “Can makeup hide the wounds of our oppression?” Protestors also performed skits on female oppression but, despite media reports at the time, they did not burn bras. A “freedom trash can” was provided for physical representations of women’s oppression, such as bras, false eyelashes, wigs and women’s magazines, but because of the wooden boardwalk, they couldn’t light anything on fire.

[in-text-ad-2]

Women’s Strike for Equality, August 26, 1970, Nationwide

Organized by the the National Organization for Women (NOW), the nationwide Women’s Strike for Equality was held on August 26, 1970, on the 50th anniversary of women’s suffrage. Multiple marches took place throughout the country, totalling about 100,000 women. Demonstrations were held in 90 cities and 42 states, with 50,000 women protesting in New York City alone.

The nationwide protest focused on women’s rights, including workplace equality and reproductive rights. Protesters included Betty Friedan, author of “The Feminine Mystique.” The Women’s Strike for Equality march is also often described as her brainchild.

[in-text-ad]

Take Back the Night, 1970s, Nationwide

Take Back the Night began in the 1970s as the first worldwide movement to fight against sexual violence and violence against women. Several rallies and marches of note took place during the decade: In 1972, at the University of Southern Florida, there was a march for campus resources and safety for women. In 1973, San Francisco residents protested violent “snuff” pornography films, and in 1975 a march in Philadelphia was held in response to the murder of a young microbiologist named Susan Alexander Speeth, who was stabbed just blocks from her home.

The Take Back the Night Foundation was founded in 2001 to “form a hub for information sharing, resources and support for both survivors and event holders,” and has welcomed an additional 300 event holders in the last decade.

Equal Rights Amendment Marches, 1970s, Nationwide

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which guaranteed women the same rights as men, was passed by Congress in 1972, and initially had seven years to be ratified by 38 states. A few states, including Illinois, were resistant to the amendment, however. In May, 1976, the National Organization for Women (NOW) began to rally for its ratification by bringing 16,000 supporters to Springfield, Illinois.

In August 1977, 4,000 women and men marched on Washington to demand that President Jimmy Carter step up efforts to get the amendment passed. Several days later the first of five annual ERA walk-a-thons raised more than $1.7 million. Another march on Washington followed in July, 1978, organized by NOW, in a successful bid to extend the time limit on ratifying the ERA. Despite the new 1982 time limit, only 35 states out of the 38 needed ratified the ERA, and today there is still no constitutional amendment guaranteeing equal rights.

[in-text-ad-2]

Rally for Women’s Lives, April, 9, 1995, Washington, D.C.

Described by the National Organization for Women (NOW) as “the first and largest mass action to stop violence against women,” the Rally for Women’s Lives was held in April 1995, and also aimed to influence a Republican-controlled Congress and set the political agenda for 1996, an election year. More than 200,000 people gathered on the National Mall for the rally, according to organizers.

The event was endorsed by a record 702 national and local groups, including abortion-rights supporters, labor unions, civil rights groups, gay and lesbian organizations, environmentalists and welfare recipients, and also coincided with the NOW Foundation’s Young Feminist Conference. The focus went beyond violence against women, and included such issues as welfare spending, abortion and affirmative action, and what Congress might do to restrict rights and reduce spending programs.

[in-text-ad]

Million Mom March, May 14, 2000, Washington, D.C.

Though not in response to a women’s right issue, the Million Mom March was a historic grassroots movement where women made their voices heard. It was started by Donna Dees-Thomases, a New Jersey mom, in response to gun violence. Dees-Thomases launched a website to bring moms together and to voice their concerns in protest.

On Mother’s Day, May 14, 2000, more than 750,000 moms and advocates marched on the National Mall in Washington D.C. The march included a “wall of death,” displaying more than 4,000 names of victims of gun violence.They were joined by additional marches in more than 60 cities across the country, for a total of 1 million participants, including politicians and celebrities. Million Mom March chapters are still active today across the U.S.

[in-text-ad-2]

March for Women’s Lives, April 25, 2004, Washington D.C.

In response to the George W. Bush administration’s anti-abortion policies and his possible re-election that November, the March for Women’s Lives drew a large crowd to the National Mall in Washington, D.C. on April 25, 2004. Estimates of participants ranged from 500,000 to as many as 1 million, with then-Sen. Hillary Clinton and actresses such as Whoopi Goldberg and Susan Sarandon attending.

The march was organized and led by the National Organization for Women (NOW), along with other women’s rights and social justice groups, including Black Women’s Health Imperative, Feminist Majority, National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health, Planned Parenthood, and the ACLU. The rally had the same name as earlier reproductive rights marches organized by NOW in 1989 and 1992, and focused on reproductive health care issues, such as abortion, birth control and emergency contraception.

Women’s March, January 21, 2017, Nationwide

On January 21, 2017, protestors packed the National Mall with a crowd that eclipsed the previous day’s presidential inauguration attendance. Started on social media, the Women’s March gained momentum through Facebook when a Hawaii woman named Teresa Shook shared the idea for a pro-woman march in reaction to Donald Trump’s election win. After thousands initially signed up, veteran activists and organizers got involved to plan a mass event following the inauguration.

Organizers estimated the crowd to be as many as half a million people, who came from across the country to protest bigotry, discrimination and sexual assault, and the threat the Trump administration posed to reproductive, civil and human rights. On the same day marches took place across the U.S. and around the world, including more than 30 countries and even Antarctica, with more than 3 million additional participants. In President’s Trump’s hometown, New York City, around 400,000 protested up Fifth Avenue. Many marchers donned pink clothing and pink hats, known as “pussy hats” in reference to Trump’s word choice in the “Access Hollywood” tape. The march also featured appearances and speeches by many celebrities and activists, including Scarlett Johansson, Janelle Monáe, and Gloria Steinem.

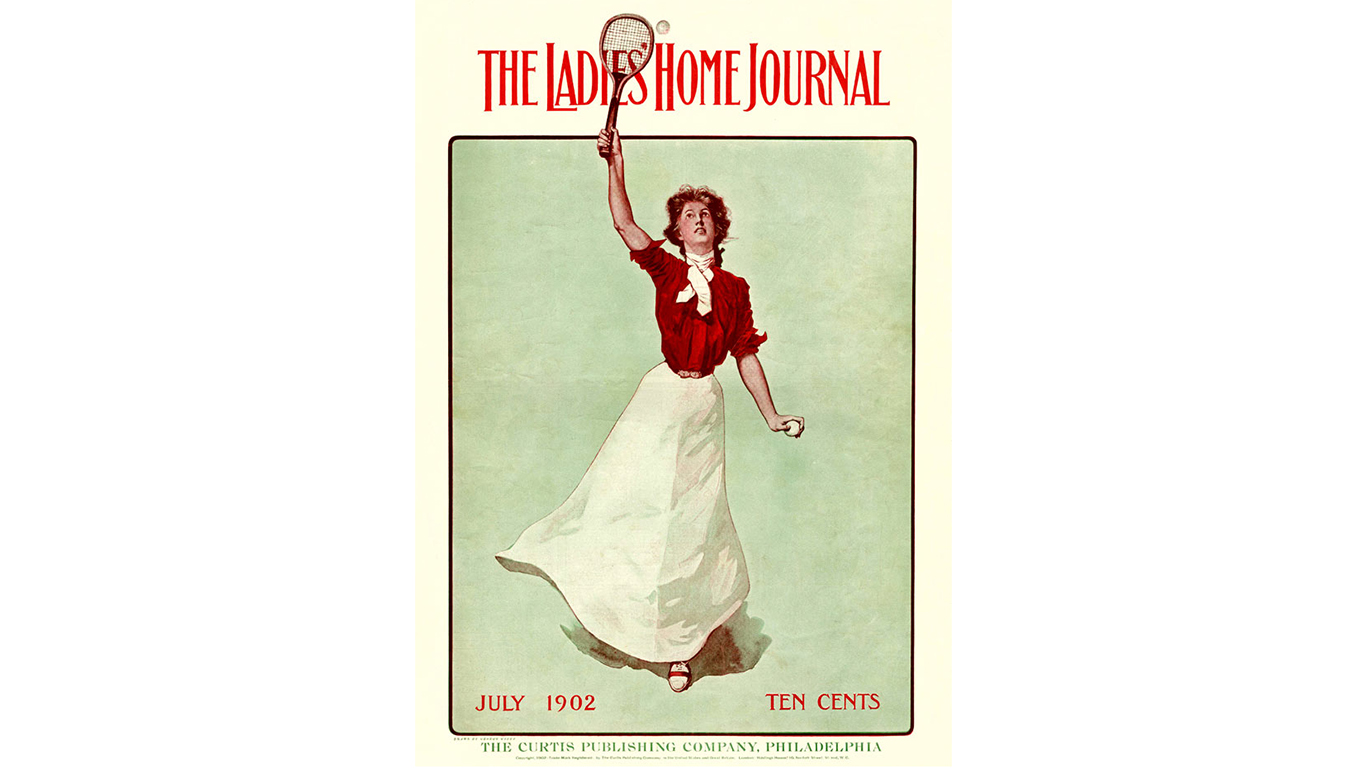

Ladies’ Home Journal Sit-In, March 18, 1970, New York City

Although not strictly a march, the protest started a change in how women’s magazines are run. Today’s they are known for their female editorial leadership, but as recently as 1970, men ran the editorial pages of a publication called “Ladies’ Home Journal.” At the time, it was the second most-read magazine in the country, with 14 million monthly readers. On March 18, 1970, around 100 women barged into the Ladies’ Home Journal offices and refused to leave for 11 hours.

The magazine’s motto was “Never Underestimate the Power of a Woman,” but, as protestors pointed out, its focus was only on women as happy housewives interested only in beauty, homemaking and motherhood. The “Can This Marriage Be Saved?” column gave advice on how to rescue even abusive marriages. The activists demanded an end to the column, an all-female editorial and advertising staff, free daycare for employees and an editorial policy against ads that were exploitative of women. Then-editor-in-chief John Mack Carter refused to resign, but did allow the protesters to produce a section of an issue. Although the protestors didn’t win most of their demands, the magazine and its competitors began to cover more women’s issues.

[in-text-ad-2]

The Average American Has No Idea How Much Money You Can Make Today (Sponsor)

The last few years made people forget how much banks and CD’s can pay. Meanwhile, interest rates have spiked and many can afford to pay you much more, but most are keeping yields low and hoping you won’t notice.

But there is good news. To win qualified customers, some accounts are paying almost 10x the national average! That’s an incredible way to keep your money safe and earn more at the same time. Our top pick for high yield savings accounts includes other benefits as well. You can earn up to 3.80% with a Checking & Savings Account today Sign up and get up to $300 with direct deposit. No account fees. FDIC Insured.

Click here to see how much more you could be earning on your savings today. It takes just a few minutes to open an account to make your money work for you.

Our top pick for high yield savings accounts includes other benefits as well. You can earn up to 4.00% with a Checking & Savings Account from Sofi. Sign up and get up to $300 with direct deposit. No account fees. FDIC Insured.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.