Special Report

Surprising Things the US Government Knows About You

Published:

Last Updated:

In 1967, Stephen Stills sang the words “Paranoia strikes deep, Into your life it will creep,” in the hit song “For What It’s Worth,” which he penned for the band Buffalo Springfield.

More than 50 years later, it’s no stretch to feel the same sentiment when considering how much information is readily available about practically everyone on the planet. Somewhere there is documentation of things even (especially!) your mother doesn’t know — from where you drove when you were supposed to be at work or school, to the image depicted in that cheeky little tattoo that seemed like such a great idea at the time.

The government, from the community to the federal level, gathers a lot of data, and not just by way of intelligence agencies. When you pay taxes, register to vote, get a driver’s license, have mail delivered or send your kids to school, you’re providing info about yourself and likely your family to a government entity. Laws regulate who can access much of that data, including whether it can be shared with law enforcement or between federal agencies. Recently, there has been an increase in inter-agency collaboration, permitting different government entities to combine data and build more detailed personal profiles than each division could have accomplished on its own.

The more agencies have a person’s information, the more likely it is for it to be mishandled in some way. With the widespread use of the internet, identity theft has become much more common. Even though victims can be targeted from across the globe, reports of this kind of crime are not evenly dispersed across the country — these are the states with most and least identity theft.

Click here to see the surprising things the government knows about Americans.

While some people tend to worry about the Big Brother effect of governmental data gathering, we give up a lot of information voluntarily, through sharing on social media, accepting privacy policies and terms of service, and applying for credit or college. Whether we share with vendors, credit bureaus, ISPs, or the world at large, there’s someone collecting the info and aggregating it. Individual companies have privacy policies, but these guidelines do not have the power of law. Unlike the government, anyone who has access to these commercial databases can pretty much use them as they please — including providing the content to law enforcement and intelligence agencies, often without a warrant or court order.

This sharing may be a plus in IDing and tracking bad actors, but it’s not necessarily so great for the rest of us. Innocent communications and purchases, research projects, ironic or sarcastic comments and even kludgy auto-corrects could seem to add up to something they’re not.

Here, we detail some of the types of personal data the government has access to, and how the various agencies go about acquiring it. Some of it can make Stills’ half-century-old concerns feel rather quaint.

1. Social media posts

Many of us bemoan our preoccupation with social media, reviling it as a time waster or justifying it as a way to keep in touch, a source of inspiration and a font of valuable information. The Department of Homeland Security agrees with us about that last part, at least. In 2012, in responding to a lawsuit filed by the Electronic Privacy Information Center, the agency copped to searching for keywords while monitoring sites such as Facebook and Twitter for at least 18 months. Last year, DHS put First Amendment activists on alert by proposing a program to track, monitor, catalog and mine content posted by social media influencers.

[in-text-ad]

2. Email history and transcripts

Thanks to Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, government entities such as the National Security Agency don’t need a warrant to monitor communications of people in the U.S. and beyond. Emails of Americans who are not targeted for surveillance can be gathered as byproducts of other investigations, a privacy violation at best. While the stated goal is keeping an eye on communications relevant to U.S. foreign affairs to protect national security, a loophole permits monitoring of virtually anyone outside the country, including journalists, political and human rights activists, lawyers, scientists, students and businesspeople.

3. Browsing history

Going back to the last century, government agencies, including the FBI and the National Security Agency, have been interested in what we’re viewing on our computers. The Federal Communications Commission’s internet privacy rules were intended to limit what companies could do with information like customer browsing habits, app usage history, location data and social security numbers. With the 2017 repeal of the internet privacy law, telecom companies are now permitted to collect and sell their customers’ private online usage information. While the repeal is said to be a boon for targeted advertising, there’s nothing to block broadband companies from selling data to the highest bidder.

4. Exact location

In 2012 the Supreme Court ruled that law enforcement can’t put a GPS tracker on someone’s vehicle without a warrant. But because of our cars and our phones, some of us have a GPS on us at all times. We’re constantly trackable by government agencies, since the U.S. government owns the Air Force-operated navigation system. Even turned off GPS-bearing devices can still ping wi-fi networks and cell towers within range, revealing our whereabouts. You may also want to think twice when an app asks you to OK your location data. Third-party data â that is, info shared with someone else â is deemed no longer private and can be obtained without a warrant.

[in-text-ad-2]

5. Charitable donations

The IRS learns about our charitable contributions through our itemized tax returns; plus charities themselves are required to file a Schedule of Contributors, aka Form 990 Schedule B, listing contributions received, with donors’ names and addresses. The IRS can share that info with the FBI and other law enforcement agencies, if they have a court order. The Treasury Department recently exempted certain nonprofits from revealing donor names and addresses, explaining in a press release that “the IRS makes no systematic use of Schedule B with respect to these organizations in administering the tax code.”

6. Drone images of property and home

With Google Earth Street View and sites like Zillow.com, we’re getting pretty used to the idea that just about anyone can take a look at our homes. But you may not know that police don’t need a warrant for anything they can observe from public airspace, say, by using drones to peek into your home, business or vehicle.

The Fourth Amendment protects us against unlawful searches and seizures in cases where people have “reasonable expectations of privacy.” As drones become more common and we grow accustomed to the aforementioned Zillow and Google depictions of our dwellings, are we losing the right to reasonably expect even the slightest bit of privacy?

[in-text-ad]

7. Credit limit and outstanding debt

Credit agencies offer one-stop shopping for an awful lot of our personal information. They gather as much info on our financial lives as they possibly can — how much credit we have, want or have been offered; the size of debt we’re burdened with, how timely or untimely we pay our bills, and whether we’ve ever attracted the attention of a professional bill collector. The agencies aggregate this info and make it available to anyone willing to pay for it, such as banks, credit card issuers, auto lenders, insurance companies, landlords and employers. Credit bureaus also provide info to the U.S. government — no court order required.

8. Online purchase history

Getting permission to spy on U.S. citizens can be a real pain in the neck for agencies such as the FBI and NSA. But there are work-arounds, of course, such as asking private companies to share the information consumers have willingly provided. The queries can be general, such as the names of everyone who has ordered a specific product within a certain time frame. Or they can be more focused, including everything purchased by a specific customer. Many companies have policies about how much they’re willing to share with law enforcement without a court order; check terms and conditions for details.

9. Video and music history

When we click to agree to the online terms and conditions, we may be consenting to more than we realize. After all, who takes the time to read screen after screen of tiny print when we’re eager to check out something all of our friends and colleagues are talking about. Websites, search engines and ISPs can collect an awful lot of data that we don’t give a second thought to, such as our video and music download history. Government agencies can ask online vendors to share the information they routinely gather, and some will do so without a court order. Who knows what the Drug Enforcement Administration, NSA, FBI or other agencies might make of some of our aural and visual obsessions?

[in-text-ad-2]

10. History of garnished wages

According to the Department of Labor, “Wage garnishment is a legal procedure in which a person’s earnings are required by court order to be withheld by an employer for the payment of a debt such as child support.” The key words here are “court order,” which essentially makes your private business available to anyone or any agency searching the public record. Information about garnishment would also be tracked by the major credit bureaus, which are overseen by the Federal Trade Commission and share their info with government agencies.

11. Tattoos

Law enforcement has kept track of distinctive physical characteristics such as tattoos for a long time; they’re even documented among descriptions on vintage “Wanted” posters from past centuries. The skin art of anyone who has been in prison is likely tracked on the FBI’s Tattoo Recognition Database. Just because you have a clean arrest record doesn’t mean your personal embellishments are not part of the public record: Advanced tattoo recognition technology is being developed by the FBI in collaboration with government researchers. That funky design or graceful character that caught your eye may cause law enforcement to connect you with “gangs, sub-cultures, religious or ritualistic beliefs, or political ideology.”

[in-text-ad]

12. Student loan payment status and payment history

It’s bad enough to be burdened with the millstone of student debt into the foreseeable future, but that information will also make its way onto your credit report, including details about your balance, payment schedule and whether you’ve fallen behind. Government agencies have access to your credit report. The Department of Education’s National Student Loan Data System tracks loan status, enrollment, contact information and more. In recent years, government agencies have become more efficient at sharing info with other departments, creating detailed “mosaic” portraits with aggregated data, which could include details culled from student loan forms.

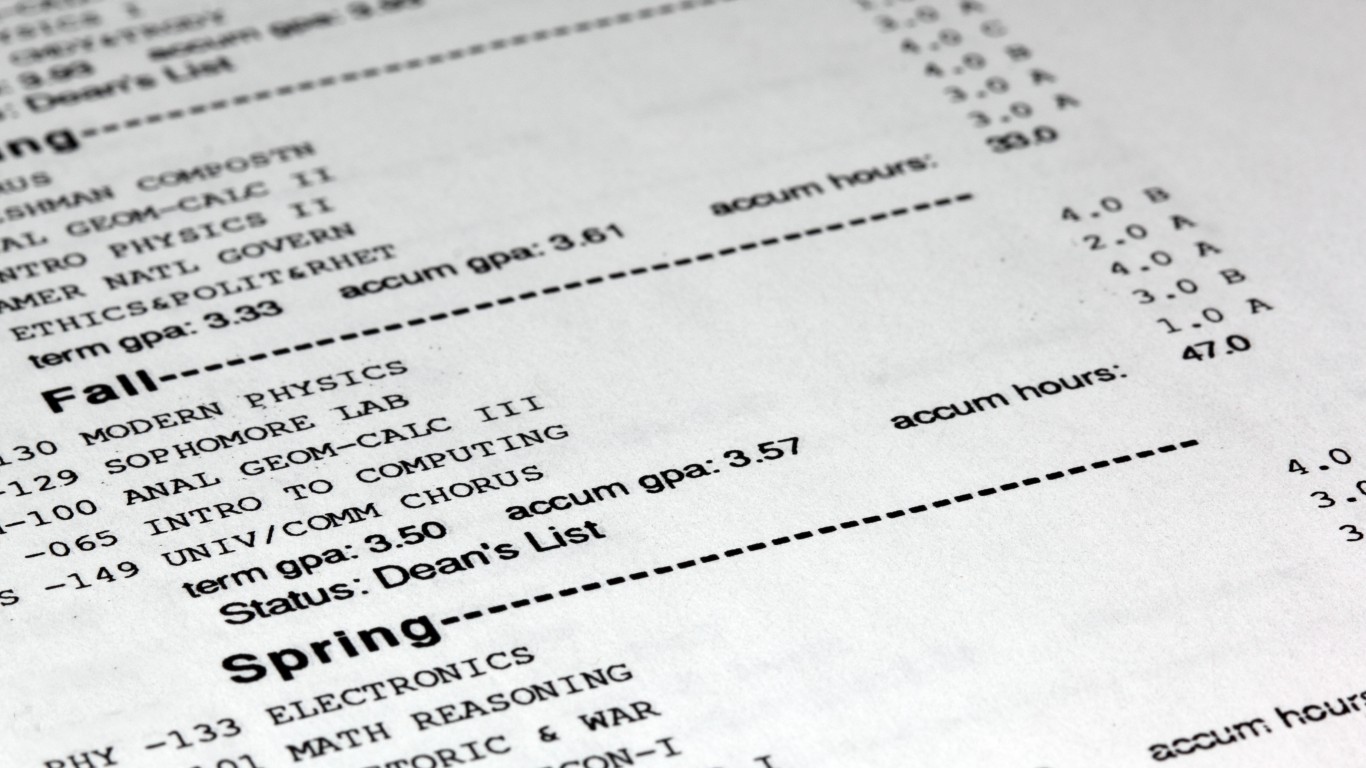

13. Education history, including class enrollment

Attending a public school? There’s a good chance the government knows what classes you’re taking. If you’re ordering textbooks or tutorials online, that info can be shared, too, which would be a good tip off as to your curriculum. The Department of Education’s National Student Loan Data System likely has your course info, too. Not to worry, they only share it with “individuals that need the information to calculate your future aid eligibility, or to resolve questions about your loans or grants on a need-to-know basis.”

14. Medical history, medications

The Social Security Administration keeps records of those enrolled in medicare, medicaid and those who have applied for disability benefits. OSHA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, is likely to be on the case if you have reported a workplace accident. We have all signed the HIPAA form at the doctor’s office, but that may not keep our medical info as confidential as you’d imagine. Law enforcement and child protection agencies, for example, may have access, though a subpoena may be required. Ordering medications online or even just searching for certain conditions and illnesses are likely to leave a traceable trail in browser histories, which ISPs and others have been known to share with law enforcement and government agencies such as the FBI and NSA. The government is also getting more efficient at inter-agency data sharing.

[in-text-ad-2]

15. Books read, passages highlighted in e-readers

While e-book sellers such asAmazon may say in their privacy policies that they’ll only give up your private info if presented with a court order, technically there’s no law prohibiting them from sharing that data. If you’re reading on a Kindle or a companion app, Amazon knows what you’re reading, right down to what page you’re on, what you’ve highlighted, your favorite time of day for reading, and any notes you’ve made. It may be time to make friends with your local library. In all 50 states, a court order is usually required to access your library records. So far only a few states have similar protection for ebooks, so you may decide to make a policy of going straight to the hard copies and studying the old-school way.

16. Travel history

If passport activity is the only thing that pops into your mind when you think about the government’s ability to track your travel, you’ve been living a sheltered life. Flight records, which the government can access, contain details of every passenger on every flight into or out of a U.S. airport. License plate scanners are ubiquitous, revealing the date, time and location of every car passing by. And the National Security Agency can trace your movements through Global Cell-Tower Identifiers, pinged by the GPS in a car or cell phone. Even when you’re on foot, your sidewalk progress can be picked up by video cameras installed by the Department of Homeland Security.

[in-text-ad]

17. Laptop camera access

GUMFISH may sound like a new variety of edible, but its cute name belies its devious nature. It’s a plug-in used by the National Security Agency to take over your laptop’s built-in camera and snap photos and videos without your knowledge or consent. Edward Snowden alerted the world to GUMFISH’s existence a few years back. It’s also been reported that the FBI can access your laptop camera, as can hackers and others. Even former FBI director James Comey has mentioned he takes precautions and covers his laptop camera with tape.

18. Gun ownership

There’s no national gun registry — it’s prohibited by the Firearm Owners Protection Act — but that doesn’t mean there’s zero gun-related data tracking. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, better known as the ATF, holds some information, such as lists of guns reported to the agency as stolen, and unrecovered firearms suspected to be used for criminal purposes. The ATF also compiles sales reports of specific firearms, including the owner’s name and address, and traced gun records that include the retail buyer and seller. Among the data in this category are registration records from out-of-business gun stores that include name, address, make, model, serial number and caliber.

19. Phone records and transcripts

It’s illegal for the government to listen into calls from U.S. private cell phones or landlines without a court order, unless either party has given consent. However, there’s no law against collecting cell phone metadata, such as time, date, location and phone numbers of each party. In 2013 Edward Snowden revealed that the NSA collected metadata on millions of AT&T, Sprint and Verizon users. There are no restrictions on listening to calls to someone outside the country. Snowden also revealed that the NSA had created a surveillance system that could record 100% of a foreign country’s phone calls, and could review them up to a month after they had taken place.

Start by taking a quick retirement quiz from SmartAsset that will match you with up to 3 financial advisors that serve your area and beyond in 5 minutes, or less.

Each advisor has been vetted by SmartAsset and is held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests.

Here’s how it works:

1. Answer SmartAsset advisor match quiz

2. Review your pre-screened matches at your leisure. Check out the advisors’ profiles.

3. Speak with advisors at no cost to you. Have an introductory call on the phone or introduction in person and choose whom to work with in the future

Get started right here.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.