Special Report

How China's Economy Became the Largest in the World

Published:

Last Updated:

With an over 3,000-year written history, China is one of the world’s oldest civilizations. China was a global economic superpower as early as the period between 1100 and and the early 1800s. Following its conquest by European colonizers and subsequent economic decline in the 19th century, the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949. Since then, China has fully re-emerged as a dominant economic power.

China’s gross domestic product in current or nominal dollars is $14.22 trillion, second only to the United States’s GDP of $21.34 trillion, according to the latest figures published by the International Monetary Fund. On a per capita basis, China is behind more than 100 countries. Here are the 25 richest countries in the world.

China’s gross domestic product measured in purchasing power parity is $27.33 trillion, by far the largest in the world. The United States, India, and Japan follow, with a GDP (ppp) of $21.34 trillion, $11.47 trillion, and $5.75 trillion.

Nominal GDP uses market exchange rates to set the nation’s GDP — the value of all goods and services produced in a country. GDP on a PPP basis takes into account cost of living differences, and is favored by many economists for more accurately capturing quality of life. For developed countries, the differences between the two measures tend to be smaller. For developing economies, the differences tend to be larger, and most often, PPP is higher than nominal GDP, as is the case with China. Because everything is measured in U.S. dollars, the U.S. GDP in both measures is the same.

How did China become the global economic force it is today? In light of the 70th anniversary this week of the founding of The People’s Republic of China, 24/7 Wall St. reviewed events in China’s history, including each of its 13 five-year plans. We also considered several features of China’s economy, including having for decades by far the world’s largest labor force.

Click here to see how China’s economy became the largest in the world.

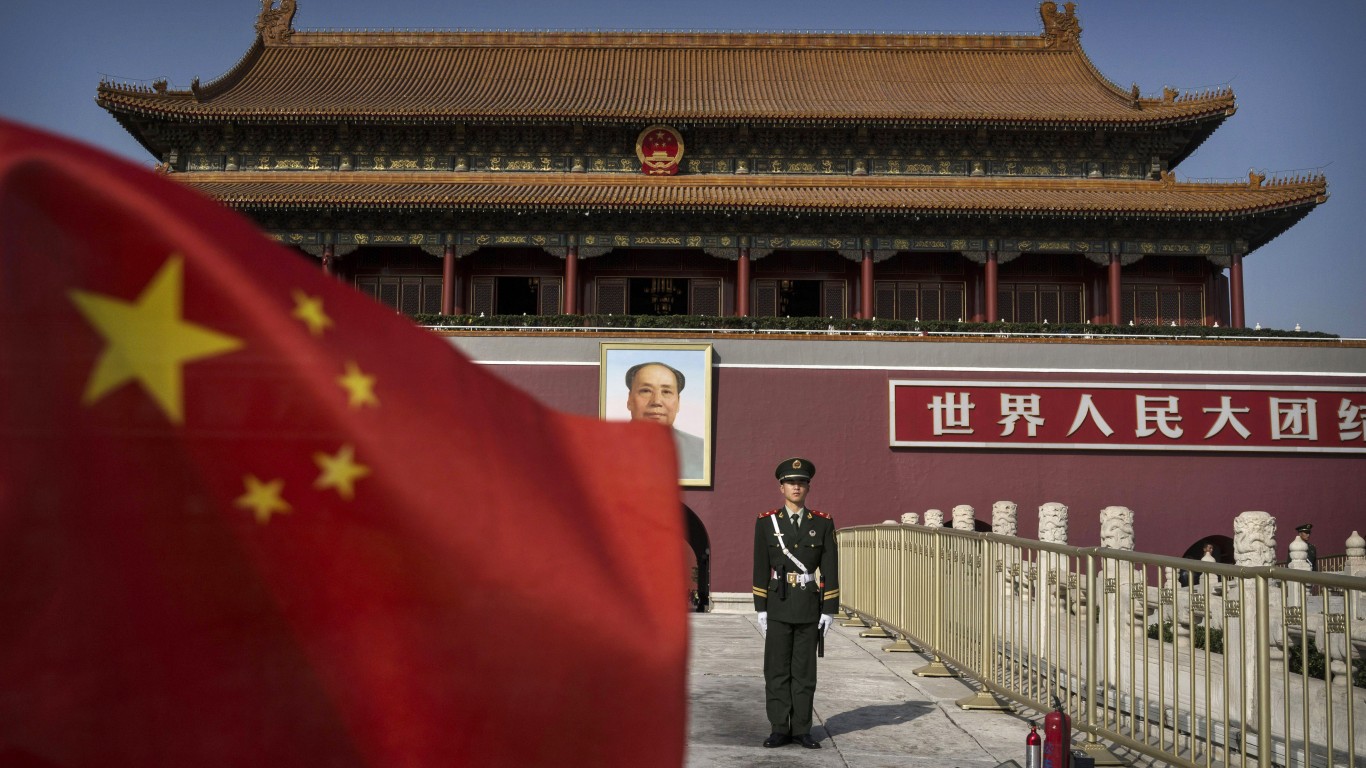

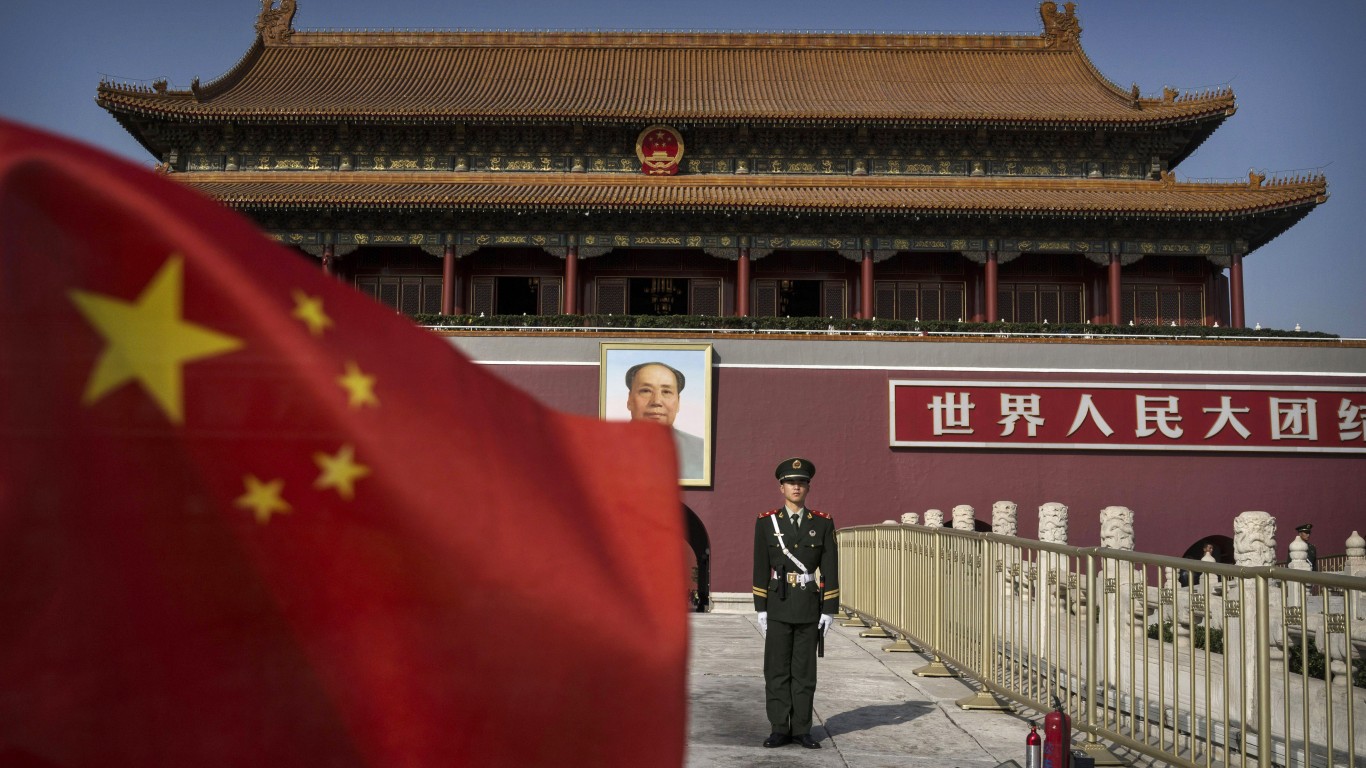

The People’s Republic of China is established, 1949

Under the leadership of Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong, the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, following a drawn-out civil war with the Nationalist Chinese government of Chiang Kai-shek. Under Mao, the economy of China was centrally planned and directed by the state, which set production goals, determined prices, and controlled resources.

[in-text-ad]

First Plan (1953-1957)

The Chinese government’s strategy for growth centered around five-year plans. The first of these initiatives began in 1953 and was modeled after the Soviet Union’s centralized economy model of intense investment in heavy industry and collectivized farms. The Soviet model did not at first promote the rapid economic growth that China would become known for later, because it was not industrialized. Eventually, in the course of the first five-year plan, it seems the emphasis on heavy industry kicked in. Workers wages rose 9% annually during this period. While farm collectivization efforts kept grain prices relatively low, especially for urban dwellers, this model did not increase grain production.

Second Plan (1958-1962)

China’s second five-year plan is called the “Great Leap Forward Period.” This aimed to build upon the achievements of the first plan. However, political ideological conflict between Mao and Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev led to the withdrawal of Soviet engineers and managers from China, hampering economic expansion. Mao also failed to learn the lesson of the failed farm collectivization efforts by the Soviet Union in the 1920s that led to famine. A similar outcome in China during the second five-year plan led to the deaths of as many as 45 million people.

Third Plan (1966-1970)

The famine in the late 1950s and early 1960s was devastating for China, which did not enact its next five-year plan until 1966. The focus of the third five-year plan was to develop agriculture and address the basic needs of the world’s most populous nation. China also made building up its national defense a priority. The nation had detonated its first atomic weapon in 1964. In addition, China planned to improve its infrastructure and boost scientific research.

The third five-year plan coincided with the Cultural Revolution, in which Mao sought to reassert control over the nation and purge those from power whom he claimed were diverting the country from the goals of the revolution.

[in-text-ad]

Massive labor force

China, the world’s most populous country, has by far the largest labor force of any nation in the world. Nearly a billion people are available for work in the country. The not just large but also cheap labor force helped encourage international investment and drive China’s remarkable economic growth for decades. Thousands of American and other foreign companies — AT&T, Adidas, Coca-Cola Foods, Caterpillar, Ford Motors, Family Dollar Stores, FedEx, Kraft Foods, Mattel, Nikon, Trader Joe’s, Victoria’s Secret, Xerox, and many, many others — own or contract factories in China, benefiting from the lower cost of manufacturing their products.

This international competitive advantage is changing, however. Economic growth has led to higher wages in China. And due to a rapidly aging population and the long-term effects of its one-child policy implemented nationally in 1980, the growth and economic edge of China’s famously large and affordable labor force will likely continue to wane.

Fourth Plan (1971-1975)

China’s fourth five-year plan set a goal of doubling the production of steel. Initially, the target for steel output was between 35 million and 40 million tons. That was revised lower to between 32 million and 35 million tons in 1973, and revised still lower to 30 million tons. The goal of the plan was for annual growth rate of gross output of industry and agriculture to climb to 12.5%. China’s economy reportedly improved starting in 1972.

Fifth Plan (1976-1980)

Following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, China’s economy began a major transformation. Under Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, the nation decentralized its economic management and allowed industrial supervisors greater autonomy in terms of determining production goals. Farmers were also permitted greater control over their enterprises. Deng’s reforms extended into China’s political and social spheres as well and included China’ controversial one-child policy intended to control the nation’s population.

Trade with the United States

China is currently the United States’ largest trade partner, trading nearly $700 billion worth of goods and services in 2018, with imports of $120.15 billion and exports of $539.68 billion. The resulting U.S. trade deficit with China of $419.43 billion — up by around $45 billion from previous years — helps explain China’s impressive economic growth in recent years.

The United States and China established trade relations in 1979, trading $4 billion that year. Opening China’s border to trade allowed foreign capital and Western companies to enter China.

Sixth Plan (1981-1985)

China’s sixth five-year plan looked to consolidate the gains from the reformation of the Chinese economy that began under the previous five-year initiative. Agricultural reforms during the prior five-year plan were yielding results by 1981. Reform initiatives helped to strengthen China’s trade and cultural links with the West, and foreign companies began to invest in Chinese enterprises. China’s export volume rose to 10th highest in the world in 1984 from 28th four years earlier.

Seventh Plan (1986-1990)

China stayed on its reform course in its seventh five-year plan. The nation continued to support state-owned enterprises and granted them more responsibility in setting production and profitability goals. The economy allowed more free market involvement, and regulations and rules were reduced. Beijing also planned to boost exports by 8% annually, a move that would have consequences for American and European companies.

[in-text-ad]

Eighth Plan (1991-1995)

China’s economy was accelerating by the time of its eighth five-year plan in 1991. Among the economic revisions were changes to the financial system that included tax decentralization and the addition of a value-added levy. The nation separated policy finance from commercial finance. China also opened up more cities to foreigners and created more economic development zones. China began work on its massive Three Gorges Dam, the world’s largest hydroelectric project, in 1994. The dam was mostly completed by 2006.

China’s diaspora or overseas Chinese

Because of its massive population, the size of the Chinese population living abroad has also been remarkably large. Close to 4 million Chinese citizens reside in the United States alone.

The millions of Chinese citizens living abroad, many of whom have left China for economic opportunities, sent remittances estimated at $64 billion in 2017, as reported by the World Bank’s Migration and Development Brief. The Chinese economy benefits further when its citizens working abroad return to China, bringing with them their expertise gained mostly in Western countries.

Ninth Plan (1996-2000)

China’s economy continued its robust growth during the ninth five-year plan period, expanding at an annual rate of 8.3%. State-owned entities were converted into corporations, and many became listed as public companies on equity markets inside and outside the country. The market system continued to evolve, with capital supply expanding and technology improving. Exports grew by 67% during the five-year period from 1995, to $249.2 billion. China’s GDP (purchasing power parity) in 2000, at the end of its ninth five-year plan, was $4.5 trillion.

[in-text-ad]

Tenth Plan (2001-2005)

The focus of China’s 10th five-year plan was on developing the nation’s information industry. During a meeting of the 15th Central Committee of the Communist Party, session attendees said so-called informatization was crucial to promoting economic advancement, modernization, and national security, as China entered the 21st century. In 2005, China’s GDP (purchasing power parity) was $8.88 trillion.

Efficient and rapid military spending

Sovereign nations use their military forces, expenditures, and assets not just for defense purposes but to further the country’s economic interests as well. The United States most notably has leveraged its military power for diplomatic reasons and economic investments (e.g., commercial contracting with Japan, South Korea, and Germany) for decades. China continues to modernize and bolster its military for similar reasons. The best, most recent example of China leveraging its military to support economic growth is its claim over the South China Sea, an important shipping route for China and other Asian countries. There could also be oil and gas in the area. In 2016 more than $800 billion worth of products shipped from China travelled through the South China Sea. The total value of the South China Sea to China’s trade is estimated at nearly $1.5 trillion.

While China’s nuclear capabilities remain distant to the United States’s stockpile, the country’s overall military expenditure of $228.2 billion is one of the largest and fastest growing of any nation.

Eleventh Plan (2006-2010)

China’s 11th five-year plan focused on expanding domestic consumption as a way to balance the economy, which was powered by investment and exports. The goal of the nation was to raise income, boost domestic consumption, and raise the living standard of the people. China also intended to shift its foreign trade growth model to better quality products from just trade volume. In the document about the five-year plan, Ma Kai, chairman of the National Development and Reform Commission, acknowledged weakness in the agricultural and service sectors of the economy and said those areas needed to be upgraded. By the end of the five-year period, in 2010, China’s GDP was $10.09 trillion.

[in-text-ad]

Twelfth Plan (2011-2015)

The main goals of China’s 12th five-year plan were for the economy to grow at a 7% annual pace, to create 45 million jobs in cities, to limit unemployment to below 5%, and to keep prices stable. Economic restructuring would continue by increasing domestic consumption and raising the service sector’s portion of the GDP. The nation also planned to boost funding for research and development to 2.2% of GDP. Rapid economic growth during this period led to GDP (purchasing power parity) of $21.14 trillion, more than double the figure from 2010.

Thirteenth Plan (2016-2020)

The 13th five-year plan aims to shift the economic emphasis to innovation and its role in the Chinese economy from growth that had been stoked by capital accumulation. The nation also aims to better integrate urban and rural development and provide equal access to basic services and provide better healthcare. China also plans to make better use of resources and move toward a lower-carbon economy, using more renewable energy sources. Other priorities include strengthening the nation’s financial system, attracting foreign investment, and encouraging Chinese companies to compete internationally.

The world’s biggest economy

While economists use a variety of metrics to gauge a country’s economy, China’s gross domestic product measured in purchasing power parity of $27.33 trillion is by far the largest in the world. The United States, India, and Japan follow, with a GDP (ppp) of $21.34 trillion, $11.47 trillion, and $5.75 trillion, respectively. China’s gross domestic product in current or nominal dollars is $14.22 trillion, second only to the United States’s GDP of $21.34 trillion, according to the latest figures published by the International Monetary Fund.

The Chinese corporations Sinopec Group, China National Petroleum, and State Grid are in the top five largest companies in the world by revenue. Seven other Chinese companies are represented in the 50 largest.

After two decades of reviewing financial products I haven’t seen anything like this. Credit card companies are at war, handing out free rewards and benefits to win the best customers.

A good cash back card can be worth thousands of dollars a year in free money, not to mention other perks like travel, insurance, and access to fancy lounges.

Our top pick today pays up to 5% cash back, a $200 bonus on top, and $0 annual fee. Click here to apply before they stop offering rewards this generous.

Flywheel Publishing has partnered with CardRatings for our coverage of credit card products. Flywheel Publishing and CardRatings may receive a commission from card issuers.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.