Hundreds of millions of people have died prematurely before vaccinations were developed and began to be routinely administered. Fear of paralysis or death from polio and smallpox was a reality for people everywhere until a few decades ago.

Today, we live with the risk of contracting the novel coronavirus, for which there is no treatment, but there may soon be a vaccine. An emergency use authorization is expected later this month for a Pfizer vaccine. If Moderna, a biotechnology company, gets an authorization, too, then about 40 million vaccines will me available by the end of 2020.

More than 66.2 million cases have been confirmed worldwide, and over 1.5 million deaths have been reported. In the United States, the COVID-19 has already killed 70,000 people since the virus was first detected in the country at the end of January. These are the states where COVID-19 is spreading the fastest right now.

The global pandemic is a reminder of what the world used to be before vaccines helped eradicate many deadly diseases and what it could have been like without immunizations — hundreds of thousands of people dying prematurely. 24/7 Tempo compiled a list of vaccines that have saved the most lives over the last century after reviewing information about the deadliest diseases and pandemics in history from the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The fight against viruses and other infectious diseases is far from over. Still, while many of the viral diseases on this list have no treatment, they are not spreading widely because of vaccines. These treatments have prevented at least 10 million deaths between 2010 and 2015. A lot more people are healthy and not living with a debilitating disease because of immunizations.

Click here to read about the vaccines that have saved the most lives.

To identify 12 vaccines that have saved the most lives, 24/7 Tempo reviewed information from the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention about the deadliest diseases and pandemics in history. We selected the conditions for which a vaccine has been developed and routinely administered across the world and that as a result, the disease has been completely or nearly eradicated. Some of the vaccines are mandatory by a certain age in many countries, including the United States; others are highly recommended or mandated if people travel to a region where the disease the vaccine can help prevent is common.

Smallpox

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: 300 million in the 20th century

> Vaccine introduced: 1796

> Vaccine impact: 5 million lives a year saved

There are theories that smallpox originated in the third century B.C. in Egypt, but the disease’s exact origin is unknown. Smallpox, which caused a high fever and a rash over the skin, killed nearly one in every three people who contracted it. Death toll estimates vary, but the most cited figure is 300 million in the 20th century alone. Transmission was through close contact or touching contaminated fabric.

While there have been earlier reports of relatively successful inoculation methods in Asia and Africa, it wasn’t until the late 18th century that Edward Jenner, an English doctor, was able to derive a smallpox vaccine. There were vaccination efforts in different parts of the world throughout the next century and a half, but still some 50 million were infected each year. The vaccine has also improved over time, and by the 1960s the World Health organization embarked on a global eradication campaign that lasted until the late 1970s. The WHO declared smallpox eradicated in 1980. Today, the deadly virus is known to exist only in secured laboratories in the United States and Russia.

[in-text-ad]

Pertussis (Whooping cough)

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: 160,000 a year worldwide

> Vaccine introduced: 1914

> Vaccine impact: 160,700 lives a year saved

Pertussis is also known as the “100-day cough” because the infection can last for 10 weeks or longer. The disease, whose symptoms include coughing fits, is most dangerous for babies. It can cause serious complications particularly in children and babies, including pneumonia, apnea, and death. Whooping cough epidemics have been recorded since the Middle Ages. A vaccine was developed in 1914 and was later combined with tetanus and diphtheria shots to become widely available.

The Cleveland Clinic estimates that more than 160,000 lives a year have been saved since the vaccine was introduced more than a century ago. Before the vaccine, there were about 200,000 pertussis cases a year in the United States alone compared with just over 13,500 a year nowadays. Two pertussis vaccines are administered over the course of a child’s first 12 years of life to help protect against whooping cough, though they don’t offer lifetime protection. A booster dose is recommended for preteens at 11 or 12 years of age.

Tetanus (Lockjaw)

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: 787,000 a year worldwide

> Vaccine introduced: 1924

> Vaccine impact: 96% reduction in mortality since 1988

Tetanus is a bacterial infection that has no cure. It affects the nervous system, leading to painful muscle spasms, jaw cramping, fever, and seizures, among other symptoms. Complications can include broken bones, pulmonary embolism, and difficulty breathing that can be fatal in 10% to 20% of cases.

The disease-causing bacteria can be found in soil and can enter the body through a cut or a burn. About 34,000 newborns died from neonatal tetanus worldwide in 2015, a 96% reduction since 1988, when an estimated 787,000 babies died from the infectious disease. The reduction was largely due to scaled-up immunization, according to the WHO.

A tetanus vaccine was developed in the mid-1920s and became widely available in 1938. A few years later, it was combined with other vaccines. Today, tetanus toxoid-containing vaccines, such as variations of the combined diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccines, are included in routine immunization programs. Boosters vaccines are recommended every 10 years in order to maintain protection against the infection, though some research suggests a booster shot is needed every 30 years.

Diphtheria

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: 15,000 Americans in the 1920s

> Vaccine introduced: 1921

> Vaccine impact: Almost 100% decrease in cases

Diphtheria, which spreads by airborne droplets or saliva, is a bacterial infection of the nose and throat that can obstruct swallowing and breathing and cause severe complications including paralysis, nerve damage, pneumonia, and death. The disease was a major cause of death among children before a vaccine was developed in 1921. That year, more than 15,000 children died from diphtheria and about 206,000 were infected in the United States alone. Between 2004 and 2017, there were only two cases of diphtheria nationwide, according to the CDC.

Though the total number of cases has significantly dropped since the 1920s, the death rate has not changed much and remains at about 5% to 10%. It may reach higher than 20% in children younger than 5 years and adults older than 40 years. People who contract the infection are treated with antibiotics.

[in-text-ad-2]

Measles

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: 2.6 million a year worldwide

> Vaccine introduced: 1963

> Vaccine impact: 23.2 million lives saved between 2000-2018

Measles, a severe infection that causes high fever and red, blotchy skin rash and attacks the respiratory tract, is one of the most contagious viral diseases in existence. About 4 million cases were reported every year until a vaccine was introduced in 1963. The mortality rate is 1 to 2 per 1,000 cases. Overall, the number of infected people has gone down as vaccination has become common or, in some countries, mandatory. Immunization has resulted in an 84% drop in deaths from the infection between 2000 and 2016 worldwide, preventing 20.4 million deaths worldwide. In the United States, the MMR vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella is required for children attending public schools.

While the benefits of immunizations are very well established, there is a growing movement in America and across the world against vaccinations. Numerous studies, including recent research published in the journal PLOS Medicine, have found a higher prevalence of infections in urban areas that allow for nonmedical exemptions — rules that permit parents not to vaccinate their kids based on their beliefs. A 2018 global measles outbreak killed more than 140,000 people, most of them children under 5, according to the WHO and the CDC.

Seasonal Influenza (Flu)

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: 290,000 to 650,000 a year worldwide

> Vaccine introduced: 1942

> Vaccine impact: Reduces risk of getting sick by up to 60%

An influenza vaccine is widely available, but people are not required to get vaccinated. The CDC has estimated that influenza, a very common illness for which there is no treatment, has resulted in up 61,000 deaths every year in the U.S. since 2010. The 2017-2018 flu season was the deadliest since tracking began in 1976, killing 80,000 people in the United States alone.

The flu virus has many strains that are quickly mutating. That, in addition to the fact that antibody levels decline over time, make a flu shot necessary every year. The flu vaccine can reduce the risk of getting sick by between 40% and 60% when most common flu viruses are well-matched to the flu vaccine, according to the CDC.

[in-text-ad]

Spanish flu

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: 50 million

> Vaccine introduced: 1942

> Vaccine impact: Cross-protection from multiple related strains

The Spanish flu, the origin of which no one knows but it was not Spain, is caused by the H1N1 subtype of Influenza A virus. The pandemic in 1918, a time long before a vaccine was available, was the deadliest in recent history. More than a third of the world’s population at the time — about 500 million people — were infected, and at least 50 million died. There is still no cure for the H1N1 flu virus.

Other strains of the flu that have caused global pandemics were the 1957 H2N2, also called the Asian flu, which killed 2 million people worldwide; and the 1968 H3N2 influenza pandemic, or the Hong Kong flu, which killed about 1 million people worldwide.

Polio

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: About 50,000 between 1910 and 1960

> Vaccine introduced: 1953

> Vaccine impact: Disease is nearly eradicated worldwide

Polio, a highly infectious disease that damages the immune system and can cause paralysis, can be fatal because it can cause the breathing muscles to become immobilized. The infection’s death rate is one in 20 in children and one in about three in adults, according to the CDC.

Polio epidemics were common in the first half of the 20th century. At the disease’s peak in the U.S. in 1952, 3,145 children died. A vaccine was developed in 1953 and since then the disease has been nearly eradicated. The total number of cases has decreased by more than 99% since 1988, from about 350,000 cases that year to 33 in 2018, according to the WHO. Without the polio vaccine, the CDC estimated that more than 17 million now healthy people would have been paralyzed.

Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan are the only three countries in the world where the poliovirus is still very common.

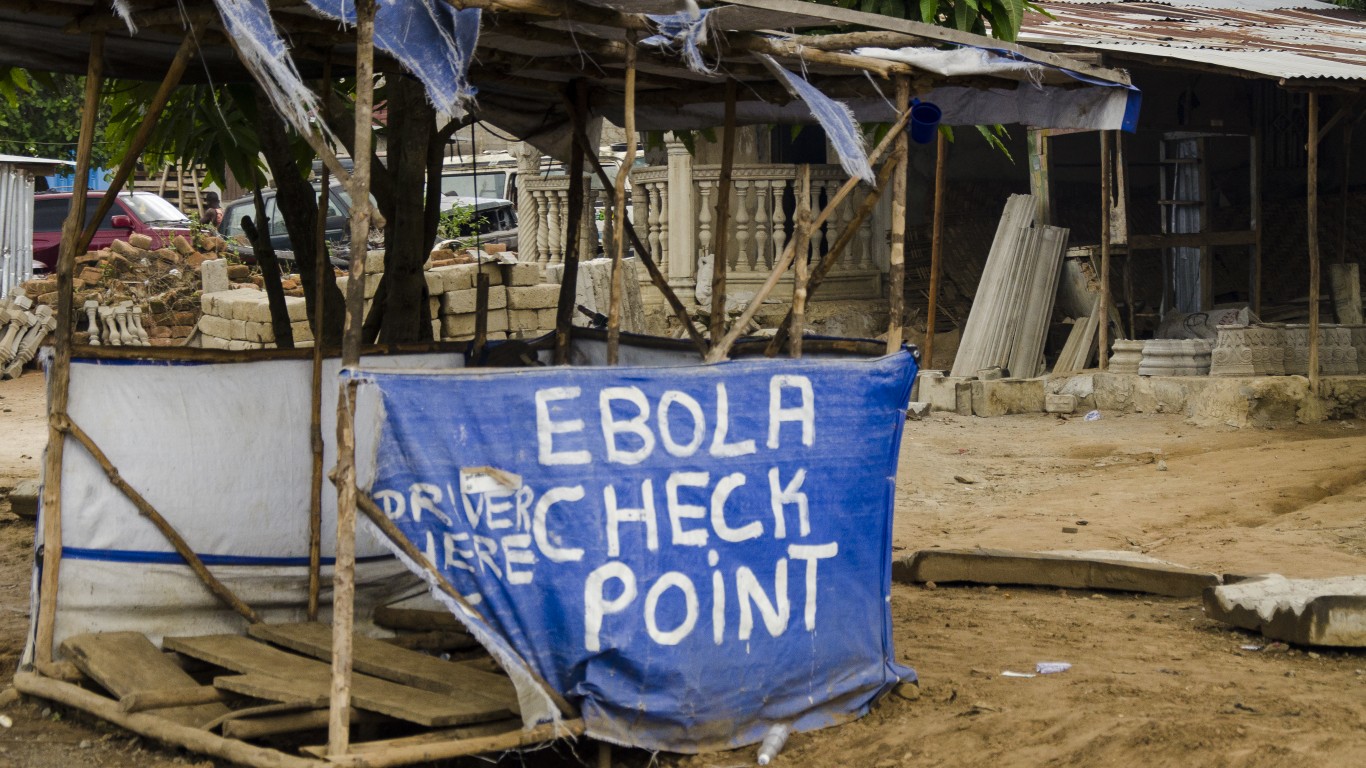

Ebola

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: 11,310 between 2014 and 2016

> Vaccine introduced: 2015

> Vaccine impact: Vaccine is effective 97.5% of the time

Ebola is a rare but severe illness with a fatality rate of around 50% that can go up to 90% as past outbreaks indicate, according to the WHO. The 2014-2016 outbreak, which started in Guinea and moved to Sierra Leone and Liberia, was the largest Ebola outbreak since the virus was first discovered in 1976. Nearly 29,000 cases and 11,300 deaths were reported. Currently, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is experiencing an outbreak. As of May 3, more than 3,462 cases and 2,243 deaths have been reported.

An experimental Ebola vaccine, called rVSV-ZEBOV, was tested in Guinea in 2015 among 11,841 people. Among the 5,837 people who received the vaccine, no Ebola cases were recorded 10 days or more after vaccination. In December 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first vaccine for the prevention of Ebola virus disease in adults.

[in-text-ad-2]

Yellow fever

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: 5,000 in 1793 in US

> Vaccine introduced: 1935

> Vaccine impact: Lifelong protection for most people

In 1793, Philadelphia was struck with a yellow fever epidemic that killed a tenth of the city’s 45,000 residents. Yellow fever damages the liver and other internal organs. There is still no cure for the viral disease that spreads by mosquitoes and can kill between 30% and 60% of those infected, according to the CDC.

A vaccine was developed in 1935 but was not licensed until 1953. A vaccine is recommended for people between 9 months and 59 years old who are traveling or living in places with yellow fever activity, and one vaccine is enough for life.

Cholera

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: Up to 143,000 worldwide

> Vaccine introduced: 1885

> Vaccine impact: 65%-85% protection for up to 5 years

Cholera, a severe intestinal illness that causes severe diarrhea, which can lead to dehydration and even death, is closely linked to poverty. The disease is transmitted by ingesting a bacterium found in contaminated food or water, common in places with poor sanitation and lack of clean drinking water. Cholera is endemic to about 50 countries, meaning the disease is always present in those areas or populations, primarily in Africa and South and Southeast Asia. According to WHO estimates from 2017, 143,000 people die of cholera every year.

There are three WHO pre-qualified oral cholera vaccines. The FDA has approved one — Vaxchora. It can be administered to adults traveling to cholera-affected areas. There is currently a WHO strategy in place to eliminate cholera in 20 countries by 2030.

[in-text-ad]

Hib (Haemophilus influenzae type b)

> Estimated deaths before widespread immunity: 371,000 a year

> Vaccine introduced: 1990s

> Vaccine impact: Lowers the risk of invasive disease

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), which can cause pneumonia and meningitis (but not the flu) affected about 25,000 children every year in the United States before a vaccine became available in the 1990s. According to WHO, until 2000, Hib was the cause of death of about 371,000 people a year.

In the United States, the overall annual incidence of Hib meningitis in children up to 4 years old was about 50 to 60 per 100,000 before a vaccine became available. An average of 25 Hib infections a year were reported to the CDC from 2003 through 2010.

Worldwide, however, less than 2% of Hib diseases are prevented because most countries don’t use Hib vaccines in their national immunization programs.

The Average American Is Losing Momentum on Their Savings Every Day (Sponsor)

If you’re like many Americans and keep your money ‘safe’ in a checking or savings account, think again. The average yield on a savings account is a paltry .4%* today. Checking accounts are even worse.

But there is good news. To win qualified customers, some accounts are paying nearly 10x the national average! That’s an incredible way to keep your money safe and earn more at the same time. Our top pick for high yield savings accounts includes other benefits as well. You can earn up to 3.80% with a Checking & Savings Account today Sign up and get up to $300 with direct deposit. No account fees. FDIC Insured.

Click here to see how much more you could be earning on your savings today. It takes just a few minutes to open an account to make your money work for you.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.