Now that we’re firmly into the 2020s, it might be time to take a look back at what America was like a century ago, during the fabled decade known as the Roaring Twenties.

In America (and to a lesser extent other countries, mostly in Europe) the years between the end of World War I in late 1918 and the Wall Street crash that came in the summer of 1929 were golden in many ways. The epoch saw economic prosperity, the birth of vital social movements, the introduction of new products, and a flowering of the arts. (These are the world’s most important events every year since 1920.)

Click here to see what life was like in the Roaring Twenties

Fads swept the land (barnstorming, flagpole sitting), styles of hair and clothing changed, Girl Scout cookies were invented. It was an age in which such now everyday objects as the radio and the automobile became available to a large segment of the population for the first time, while jazz provided the soundtrack and movies learned to talk and women finally got the right to vote. (Compare the year women won the right to vote in 46 countries.)

But it was also a decade in which racism was rampant and white supremacy was on the rise. Child labor was common and there were few protections for workers of any age. Prohibition spurred the rise of organized crime and turned America into a nation of law-breakers.

In other words, the 1920s were like any other decade, even our own — part good and part bad. Here are 30 illustrations of what life in America was like in those years.

Women gained the legal right to vote for the first time

The 19th Amendment to the Constitution, mandating women’s suffrage, was passed by Congress on June 4, 1919. At least 36 state legislatures had to ratify it, and the last of these (Tennessee) complied on Aug. 18, 1920. African-American and Asian-American women still found it difficult if not impossible to exercise their rights, however.

[in-text-ad]

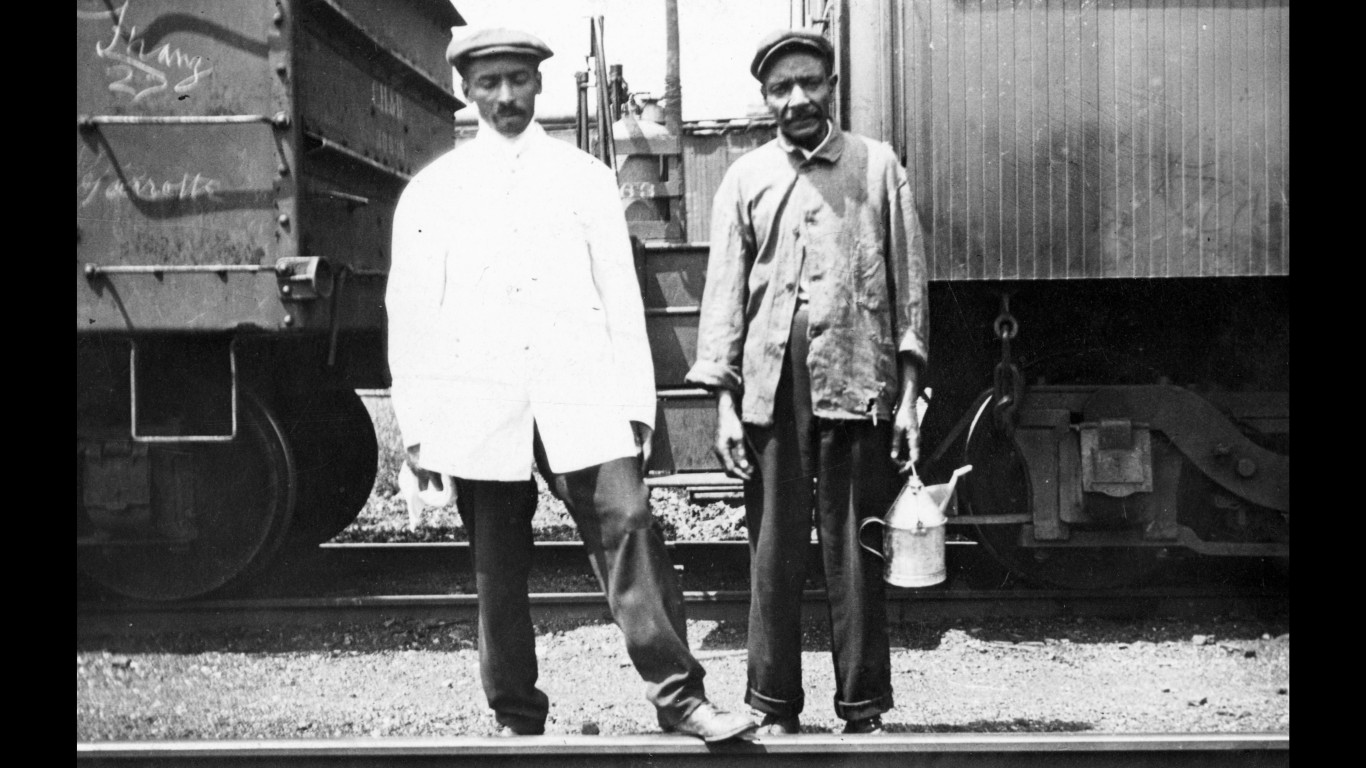

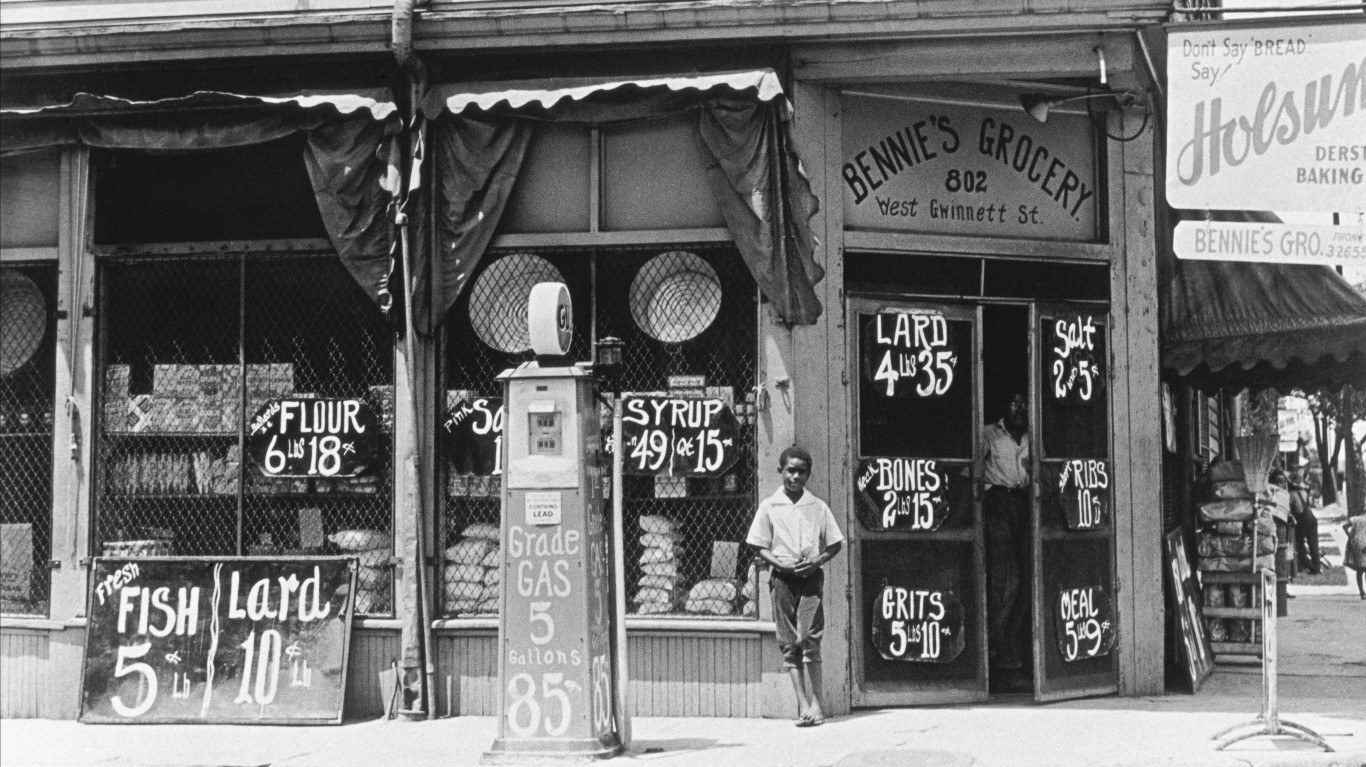

Blacks were moving north en masse

In 1910, about 90% of the country’s African-American population lived in the South. Beginning that year, in what has been dubbed the Great Migration, many started moving to other parts of the country, mostly the North, in search of work. The first wave of the movement lasted until 1930, and in the 1920s alone, about 750,000 Blacks made the trek.

Segregation was rampant

If Blacks moving out of the South hoped to find a more welcoming environment elsewhere in America, they were sadly disappointed. Zoning laws kept them out of “white” neighborhoods, Jim Crow laws were enforced in many places just as they had been in the South, and racial violence was commonplace. (In 1921 alone, rampaging mobs in Tulsa, Oklahoma, destroyed some 35 square blocks of the so-called Black Wall Street, and left as many as 300 dead.)

White supremacy proliferated

Though originally founded in the South immediately after the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan reemerged in the 1920s as a potent foe of Blacks, Jews, Catholics, and immigrants of all kinds. The organization found followers in cities in the West and Midwest as well as the North, and in the mid-1920s, claimed to have as many as five million members nationwide.

[in-text-ad-2]

Most immigrants weren’t welcome

The Emergency Immigration Act of 1921 and the National Origins Act of 1924 severely limited the number of immigrants, particularly targeting those from southern and eastern Europe. The executions of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in 1927, for a murder they almost certainly didn’t commit, was fueled by anti-Italian “nativists.” The Asiatic Barred Zone Act of 1917 had already banned all immigration from most of Asia and the Middle East.

Few married women worked outside the home

While women did join the workforce in increasing numbers during the 1920s, often as secretaries or store clerks, the majority remained at home. The commonly accepted idea, by many women as well as most men, was that women should marry, stay home, keep house, and raise children.

[in-text-ad]

There was no federal law against child labor

In 1920, about a million Americans between the ages of 10 and 15 worked on family farms, in factories, or as messenger or clerks. Safety standards were lax and there was no limitation on hours of employment. Private groups had been agitating for child labor laws since the turn of the century, but a comprehensive child labor law wasn’t passed until 1938.

There was no federal minimum wage

Though some states passed minimum wage laws of their own as early as 1912, it wasn’t until passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act (the same bill that established rules for the employment of children) in 1938 that a federal minimum wage was established. It was set at 25 cents per hour.

The 40-hour workweek was introduced in some places

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 also limited the standard work week to 44 hours, but the Ford Motor Company was way ahead of it. The company adopted a five-day, 40-hour workweek in 1926, at a time when workers commonly labored for at least 48 hours a week. Other companies eventually followed Ford’s lead.

[in-text-ad-2]

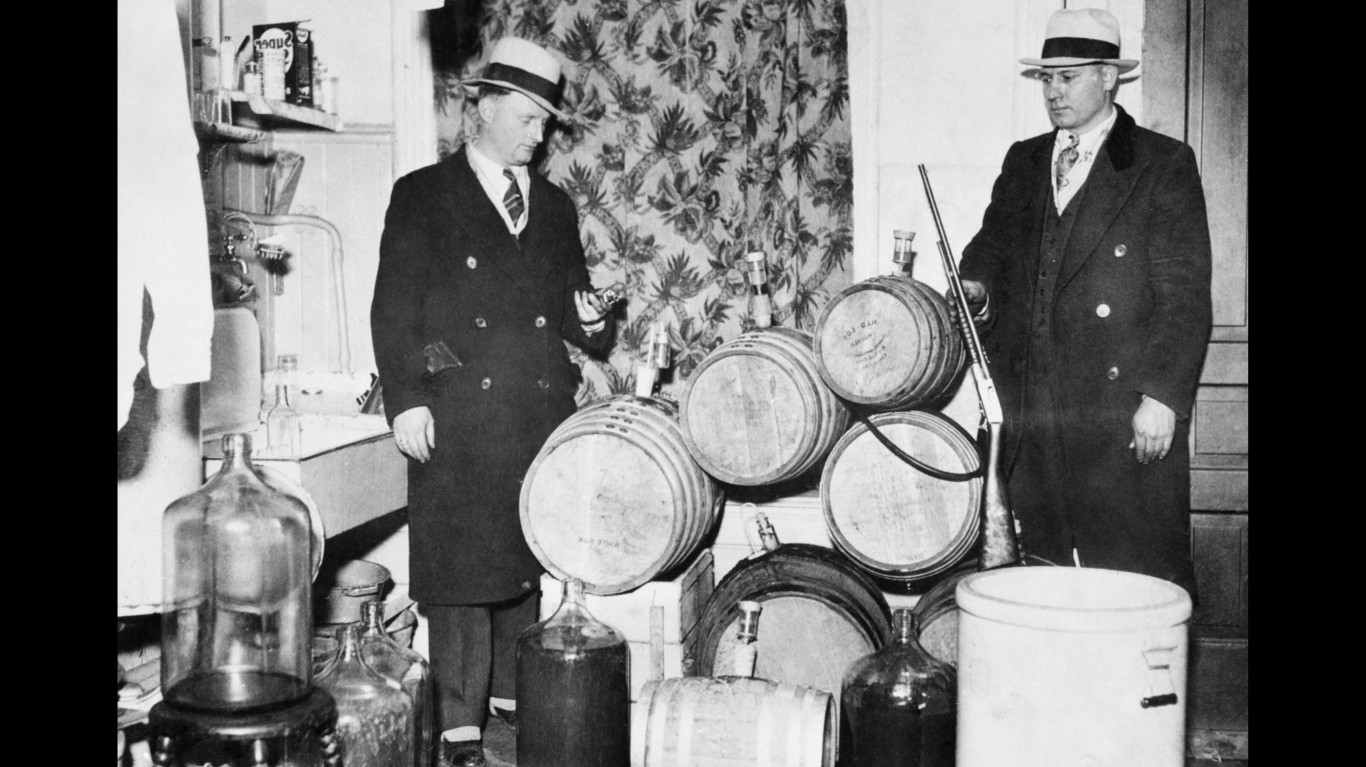

You couldn’t legally buy alcohol

Between Jan. 17, 1920, and Dec. 5, 1933, the manufacture, sale, importation, and exportation of intoxicating liquors was banned in the United States. An exception was made for the home production of wine and cider (though not beer), up to 200 gallons per year, per household — and it was never illegal to actually drink, so many people stocked up on supplies before the law went into effect.

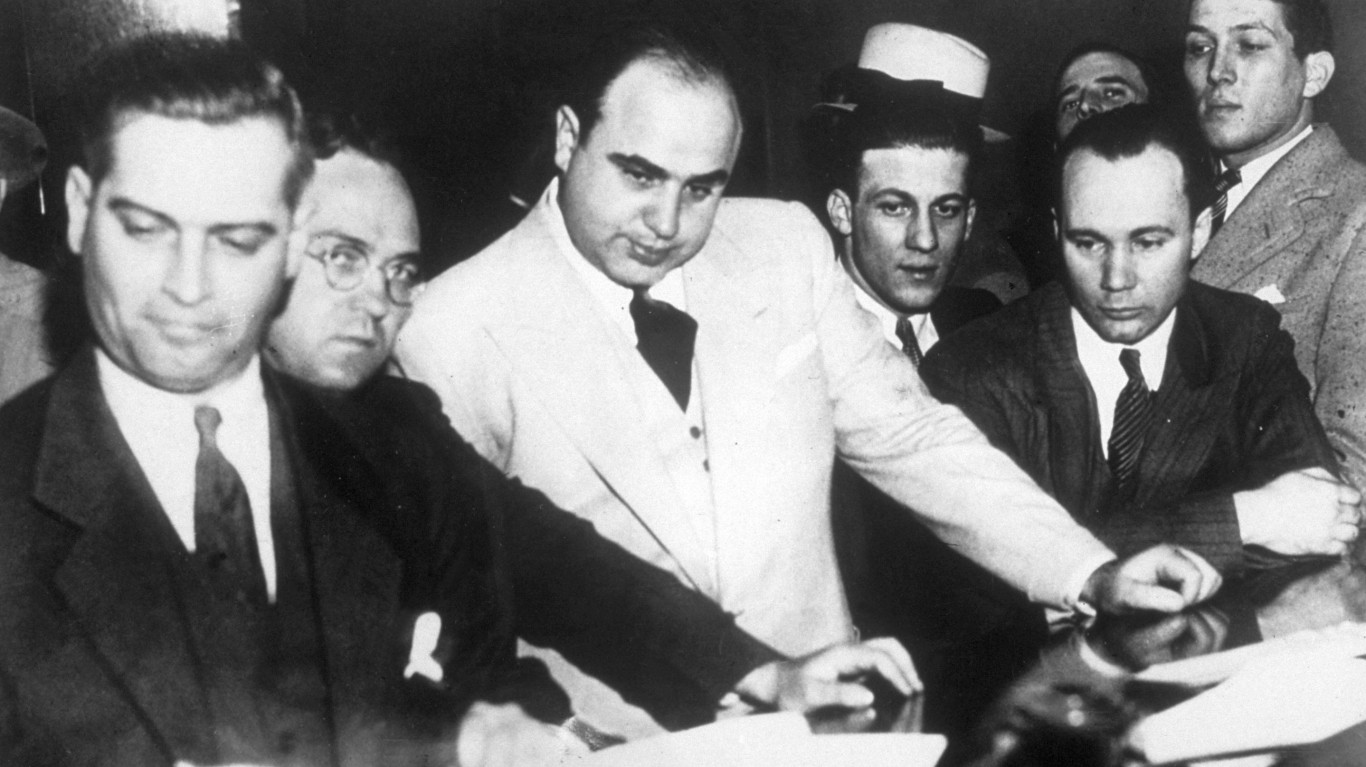

Bootleggers were getting rich

The profits to be had from bootlegging, the illegal importation of alcohol, were enormous. One famous gangster, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, was a 23-year-old mob flunky recently arrived from Sicily in 1920; by the late ’20s, bootlegging had made him a multimillionaire. Al Capone’s organization is said to have generated the modern-day equivalent of about $1.4 billion from bootlegging and related rackets.

[in-text-ad]

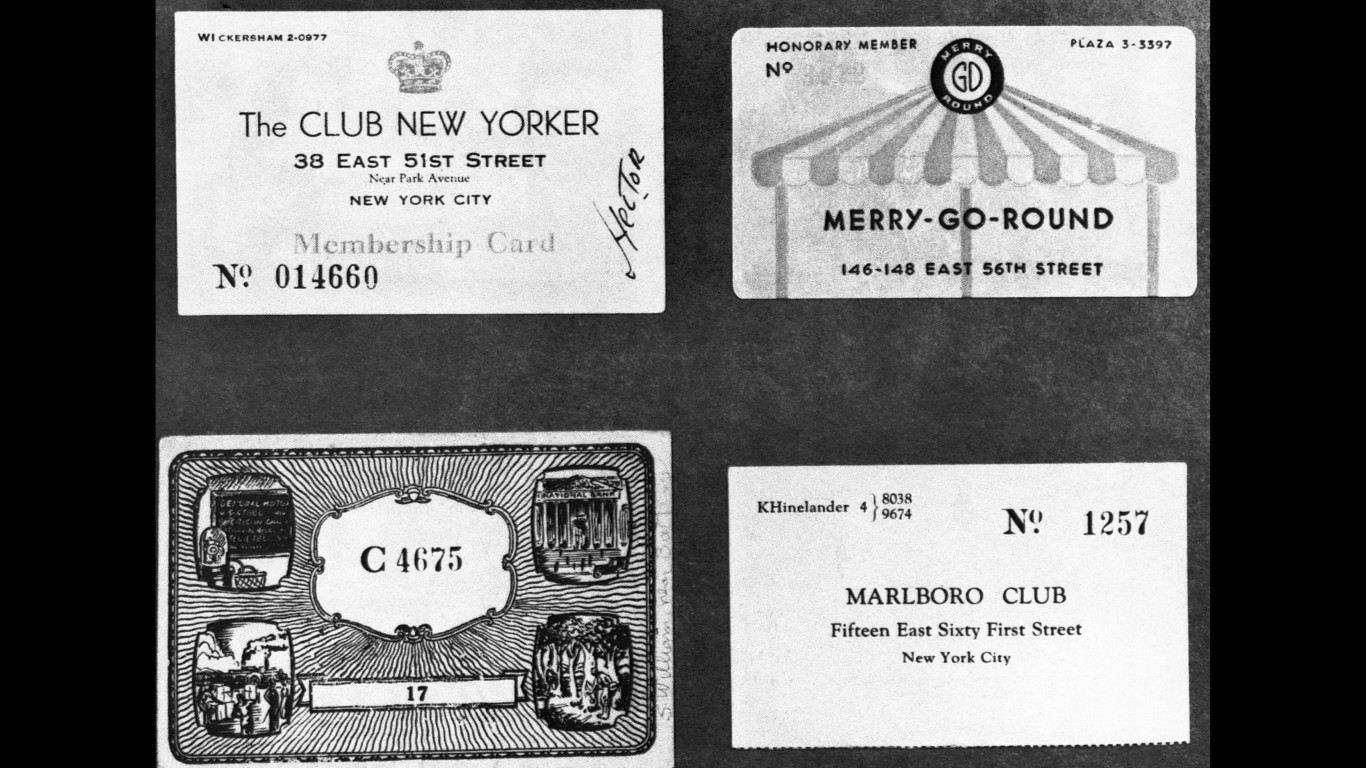

There were speakeasies everywhere

Speakeasies were illegal bars — sometimes formerly legal ones that adapted to the times but often hidden back rooms or even private apartments converted to the purpose. Serving illegally imported booze or moonshine of dubious provenance, they thrived in every corner of the country. At one time, according to some estimates, there were as many as 100,000 speakeasies in New York City alone.

Mobsters killed each other in the streets

Bootlegging is said to have put the “organized” in “organized crime,” as mobsters developed vast networks of suppliers, distributors, enforcers, accountants, and attorneys. It also engendered deadly competition. By 1926, it was said that there were more than 12,000 murders a year associated with bootlegging and related crimes across the country.

Federal agents were seen as heroes fighting gangsters

The FBI was an inefficient and politicized organization at the beginning of the decade, but J. Edgar Hoover, named director in 1924, reformed it and the Bureau began targeting the increasingly dangerous gangs that thrived as a result of Prohibition. Even better known and more appreciated by the law-abiding public than the FBI were the agents of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Bureau of Prohibition — the most famous of whom was the legendary Eliot Ness.

[in-text-ad-2]

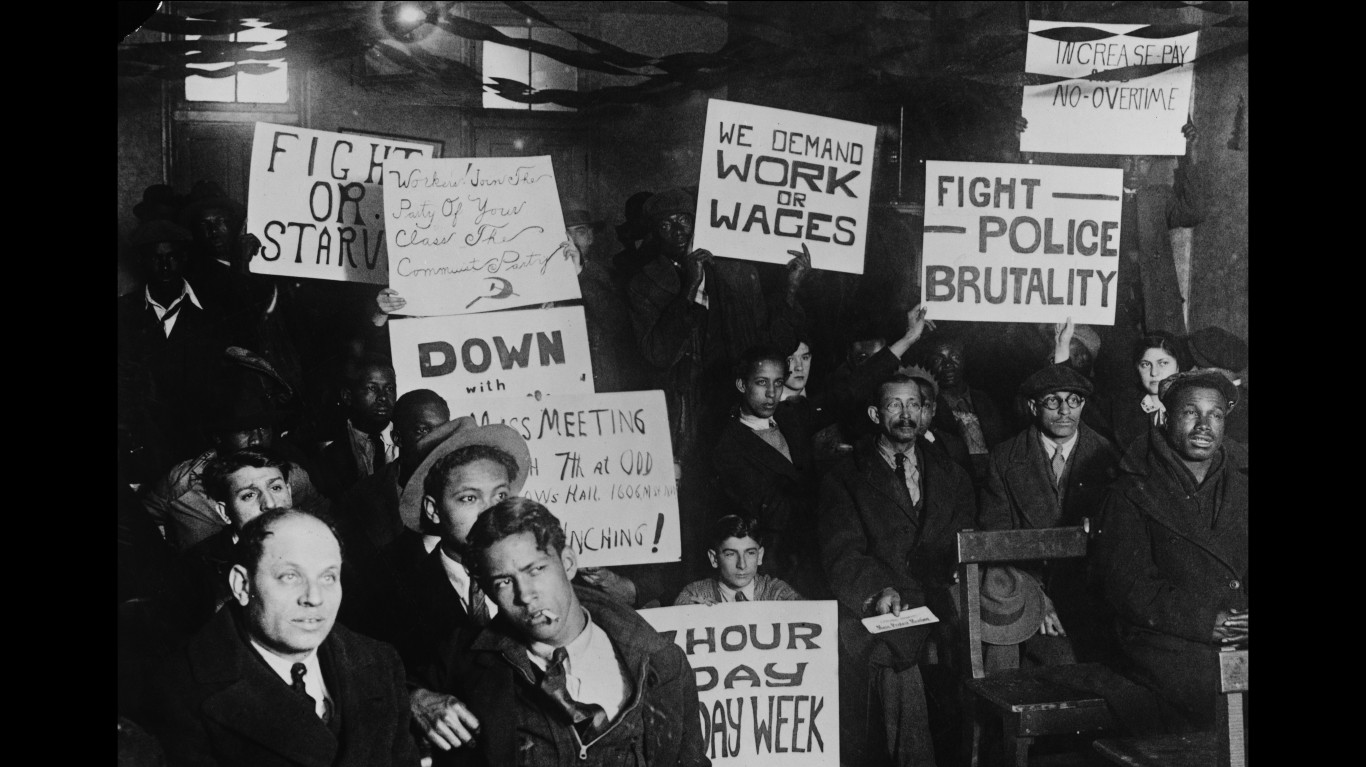

Suspected communists were arrested and deported

The first nation’s “Red Scare” was at its height from late 1919 to early 1921, and the so-called Palmer Raids, directed by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, saw about 3,000 “reds” (mostly Italians and Jews from Eastern European) arrested. Somewhere between 500 and 1,000 of them were deported. Suspected or self-avowed communists were also expelled from various labor unions and legislative bodies throughout the decade.

The latest entertainment fad was…radio

The radio, or “wireless,” came into its own in the 1920s. The first radio news broadcast aired in 1920, the first sports program (a college football game) in 1921. Hundreds of stations appeared in the following years, and Americans coast to coast gathered around radios to listen to concerts, dramatic serials and comedy shows, political speeches, and much more. Networks of stations covering almost the whole country influenced consumer tastes in music and brand-name products and reduced (though didn’t eliminate) differences in language and pronunciation from place to place.

[in-text-ad]

The prevailing music gave its name to the era: the Jazz Age

Another name for the Roaring Twenties (and one that extended into the 1930s) was the Jazz Age. Big bands gained national prominence through radio broadcasts and the proliferation of 78 rpm records. Jazz combos were often featured at speakeasies. Duke Ellington and other musical giants of the Harlem Renaissance (see below) gained increasing popularity, as did such bandleaders as Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Glenn Miller, and Fletcher Henderson.

People were dance-crazy

Unlike the bebop jazz that developed in the 1940s and the music that grew out of it, the jazz of the 1920s was meant for dancing, and the era saw an upswing in dancehalls and dance styles. The iconic dance of the time was the Charleston, but the Fox Trot, the Shimmy, the Black Bottom, the Tango, and others were popular as well. The ’20s also saw the birth of a fad for dance marathons — endurance contests at which couples competed by dancing continuously for hundreds of hours at a time.

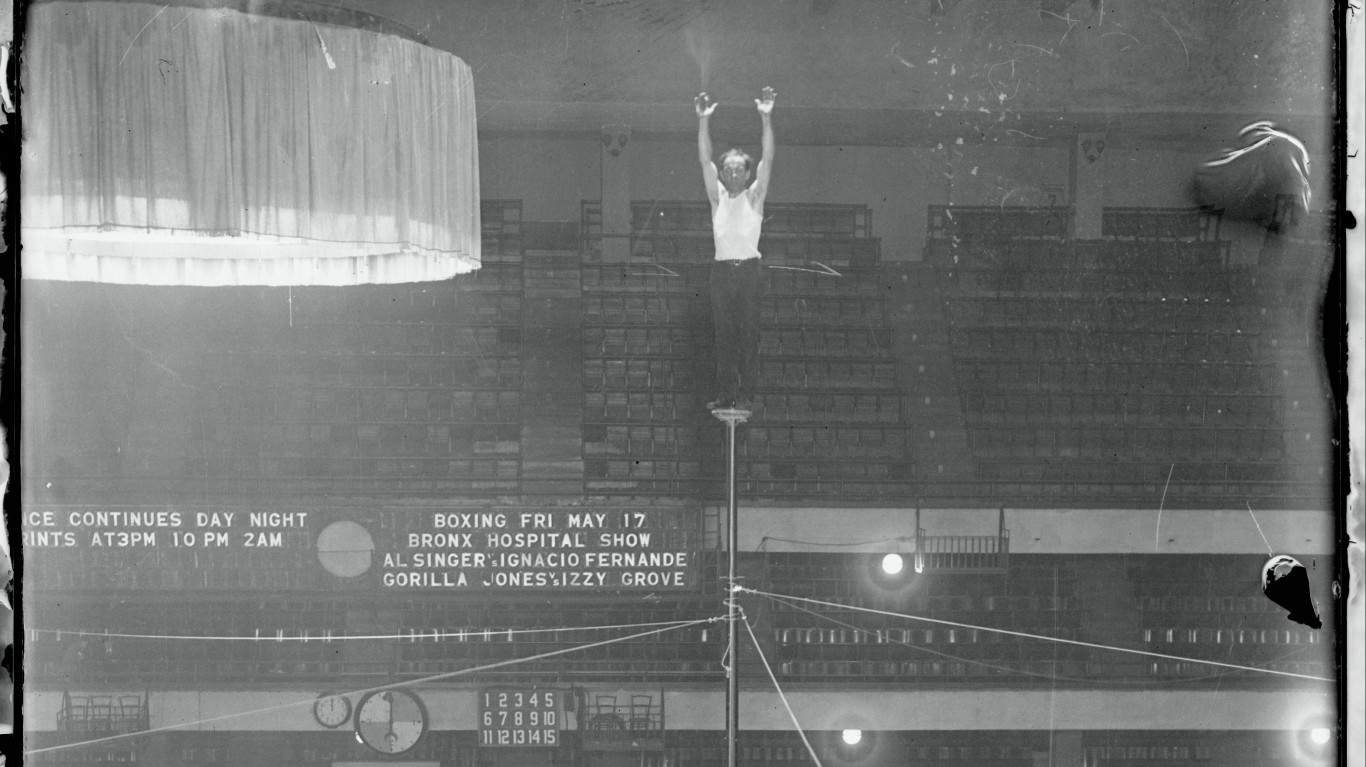

Audiences gathered to watch people sitting atop flagpoles

In 1924, an ex- sailor and movie stuntman named Alvin “Shipwreck” Kelly, on a bet or a dare, climbed up a flagpole in Philadelphia and sat on a platform that had been mounted there for 13 hours and 13 minutes. This launched one of the more curious crazes of the latter 1920s, in which men and women all over the country perched atop flagpoles and other columns, exposed to the elements, for ever-increasing amounts of time, sometimes many weeks. Though there were a few minor later revivals, the practice died out with the advent of the Depression in the summer of 1929.

[in-text-ad-2]

Vaudeville still drew massive audiences

Though vaudeville — theatrical variety shows that typically included some combination of music, dance, comedy, magic, circus acts, lectures, and/or other forms of entertainment — had been around for decades and was beginning to lose ground to motion pictures, it continued to thrive in the ’20s. By the end of the decade, it is estimated that as many as two million people a day attended vaudeville shows.

Movies were silent for most of the ’20s

Many movies now considered timeless classics were made in the 1920s, by such famed directors as D.W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Fritz Lang, and Sergei Eisenstein, but they were silent. Essential dialogue was written on cards that flashed on the screen, and the film music, if it existed, was played by a live organist or even a full orchestra in the theatre. In 1926, Warner Bros. introduced new technology that eventually allowed music and sound effects to be synchronized with on-screen images. The studio’s Al Jolson starrer “The Jazz Singer,” which premiered in 1927, was the first film to offer spoken dialogue on the soundtrack — the first so-called “talkie.” By 1930, silent movies were virtually extinct.

[in-text-ad]

Movie theatres were ornate “picture palaces”

The functional multiplexes of today, in which half a dozen or more movies screen simultaneously in adjacent small theatres, have little in common with the grand movie palaces of the past. Capacious, ornately furnished structures, full of intricate architectural details, these theatres made movie-going seem like a special event. Though they were built between the 1910s and the 1940s, the 1920s saw the peak of their popularity. It is said that hundreds of such places opened annually between 1925 and 1930.

Barnstormers — daredevil pilots — were a big deal

Traveling the country performing aerial stunts and offering plane rides to the public, barnstormers were ace pilots (Charles Lindbergh, whose solo flight from New York to Paris in 1927 was one of the decade’s signal events, was one early in his career). Though the phenomenon had begun earlier in the century, the 1920s were the heyday or barnstorming. A spate of accidents and increased government regulation in the late ’20s led to the demise of the practice.

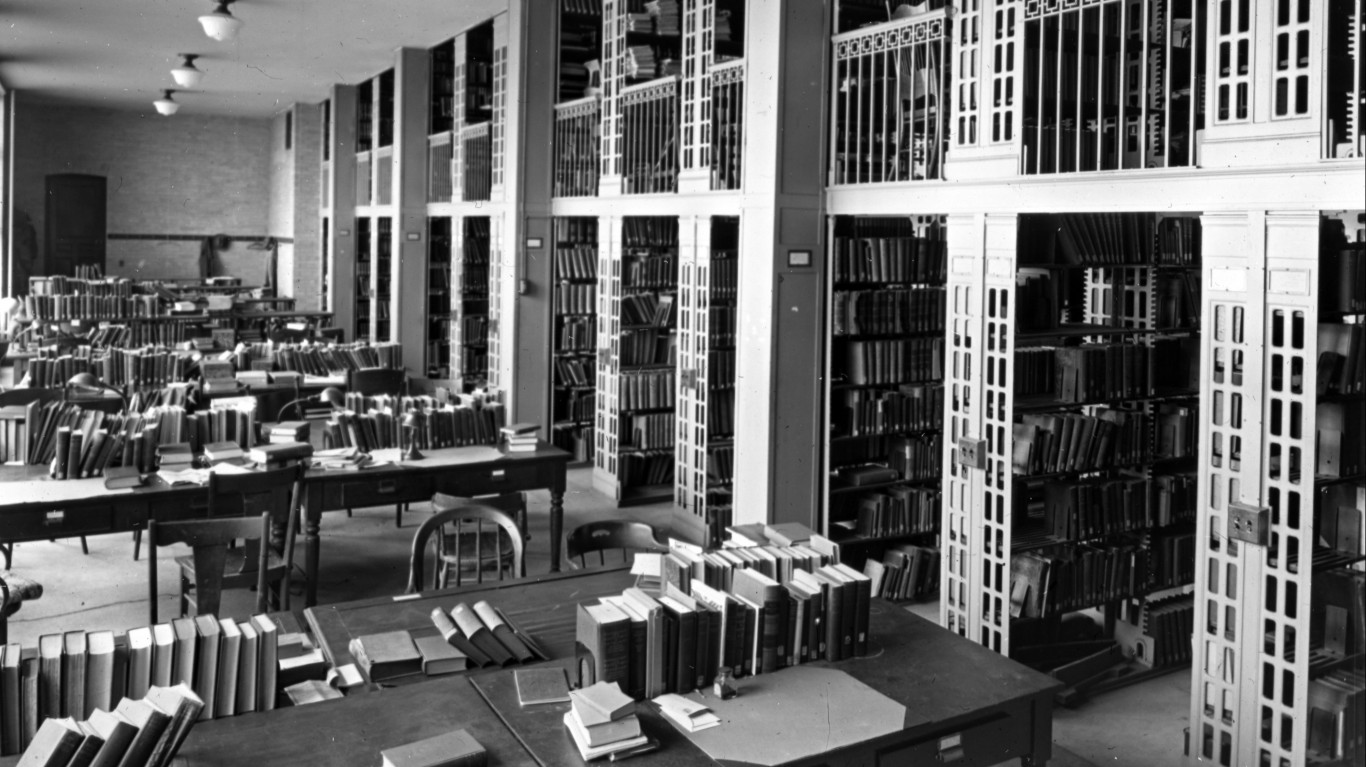

Writers like Hemingway and Fitzgerald were penning masterpieces

The 1920s were a golden age for American literature, seeing the publication of such classics as “The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald, “The Sun Also Rises” and “A Farewell to Arms” by Ernest Hemingway, “The Sound and the Fury” by William Faulkner, and “The Age of Innocence” by Edith Wharton, as well as important works by Theodore Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis, Gertrude Stein, and many more.

[in-text-ad-2]

African-American art and literature flourished in Harlem

The so-called Harlem Renaissance, a flowering of African-American literature, art, music, and theatre, is considered to have ranged from 1918 through the mid-1930s, but the ’20s were its heart. Among its key figures were authors Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, and Jean Toomer, and the poet Langston Hughes; painter Jacob Lawrence; and a host of musical figures including Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Bessie Smith, and the composer William Grant Still.

Long hair for women went out of fashion

Many women kept their hair long in the 1920s, but the hairstyle most emblematic of the era, indelibly identified with Flappers, was the bob — a short cut, typically extending to the chin line and often involving bangs. Getting the haircut made a statement. The soprano Mary Garden announced in 1927 that she considered “getting rid of our long hair one of the many little shackles that women have cast aside in their passage to freedom.”

[in-text-ad]

Girl Scout cookies were invented and sold door-to-door

Though Girl Scouts started selling cookies to raise money as early as 1917, it was in 1922 that the organization’s magazine, The American Girl, published a sugar cookie recipe and officially recommended sales of the confections as a fund-raising device. The magazine estimated that six or seven dozen cookies could be made with 26 to 36 cents worth of ingredients, and then sold for 25 to 30 cents a dozen. Using both the magazine’s recipe and family recipes of their own, troops across the country started baking, then knocking on doors to hawk the results.

People started buying new products like Wheaties, Wonder Bread, and Kool-Aid

As food production techniques and distribution methods improved in the 1920s, new processed foods, many bearing now-famous brand names, were introduced. These include Wheaties, Wonder Bread, Kool-Aid, Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, Velveeta, Popsicles, Hostess cupcakes, and Baby Ruth candy bars.

The working class could afford to buy cars for the first time

In the early years of the American automobile industry, only the wealthy had cars. The original Model T Ford, introduced in 1908, cost a then-healthy $850, but Henry Ford saw a vast potential market among ordinary folk, and successively decreased the price until it reached its lowest point — $260 — in 1925. This put it within reach of many workers, at least on credit, which is how most people bought cars even then. (Between 1919 and 1925, General Motors alone extended $810 million in credit — over $12 billion today’s dollars — to U.S. consumers.)

[in-text-ad-2]

Most drugstores had soda fountains

Soda fountains, a few of which still exist in some parts of the country, originally served just carbonated drinks and ice cream (including sundaes), but by the 1920s had evolved into lunch counters also offering sandwiches and other light fare. Commonly found in drugstores and some other retail outlets (like dime stores), they became popular places to socialize after Prohibition shut down bars.

The Average American Has No Idea How Much Money You Can Make Today (Sponsor)

The last few years made people forget how much banks and CD’s can pay. Meanwhile, interest rates have spiked and many can afford to pay you much more, but most are keeping yields low and hoping you won’t notice.

But there is good news. To win qualified customers, some accounts are paying almost 10x the national average! That’s an incredible way to keep your money safe and earn more at the same time. Our top pick for high yield savings accounts includes other benefits as well. You can earn up to 3.80% with a Checking & Savings Account today Sign up and get up to $300 with direct deposit. No account fees. FDIC Insured.

Click here to see how much more you could be earning on your savings today. It takes just a few minutes to open an account to make your money work for you.

Our top pick for high yield savings accounts includes other benefits as well. You can earn up to 4.00% with a Checking & Savings Account from Sofi. Sign up and get up to $300 with direct deposit. No account fees. FDIC Insured.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.