Hundreds of billions of locusts are currently ravaging several countries in East Africa and South Asia, causing devastating damage to crops both in the field and in storage. Swarms the size of cities are sweeping over farmland, and the numbers are projected to increase 500-fold by June if left unchecked.

Insect plagues have been documented throughout human history, causing famine and widespread hunger. 24/7 Tempo compiled 20 of the most devastating insect plagues in U.S. history, including not only incidents of ravenous swarms but also the less visible, equally insidious insects that have preyed on woodlands, fruit trees, and even livestock — many of which are classified as invasive species.

We concentrated on native and invasive insects with reported rapid population growth in the United States. All of these insects have caused the destruction of property, agriculture, or native flora and fauna. In some cases, the population surge slowed and the insects are no longer causing serious destruction. In other cases, the damage is ongoing.

Human actions can be traced to many of these plagues, whether by importing invasive species in fruit shipments, being careless about firewood transport, or causing the climate crisis. Climate crisis is also going to permanently change how these 22 crops are grown.

Click here to see the most devastating insect plagues in U.S. history

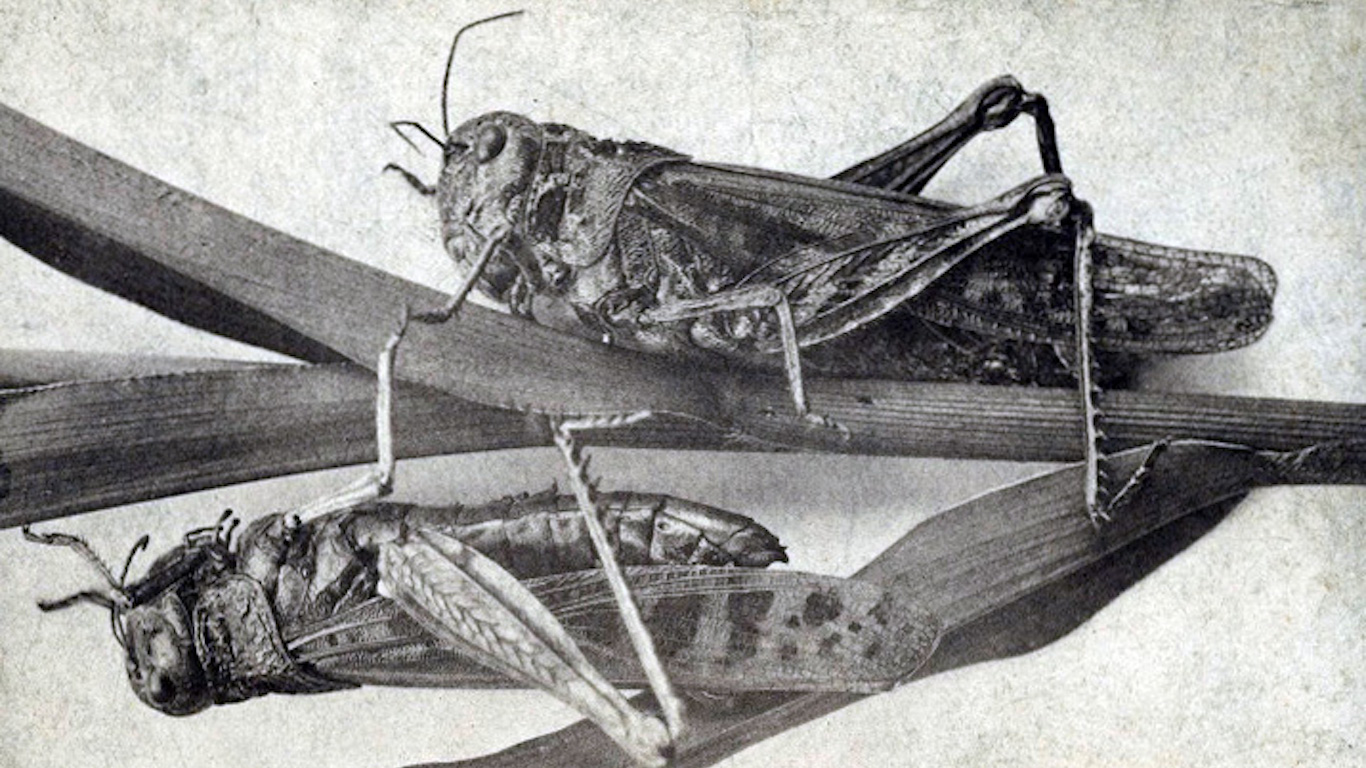

Rocky Mountain locusts

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 1874

Beginning in the summer of 1874 and peaking in 1875, swarms of Rocky Mountain locusts devastated lands across the Great Plains, from Montana to Texas. They ate not only agricultural crops and other vegetation, but also any organic material they could chew through, including clothing and leather.

Formerly declared extinct in 2014, their numbers were estimated to have been in the trillions, with swarms reportedly so big they blocked out the sun.

[in-text-ad]

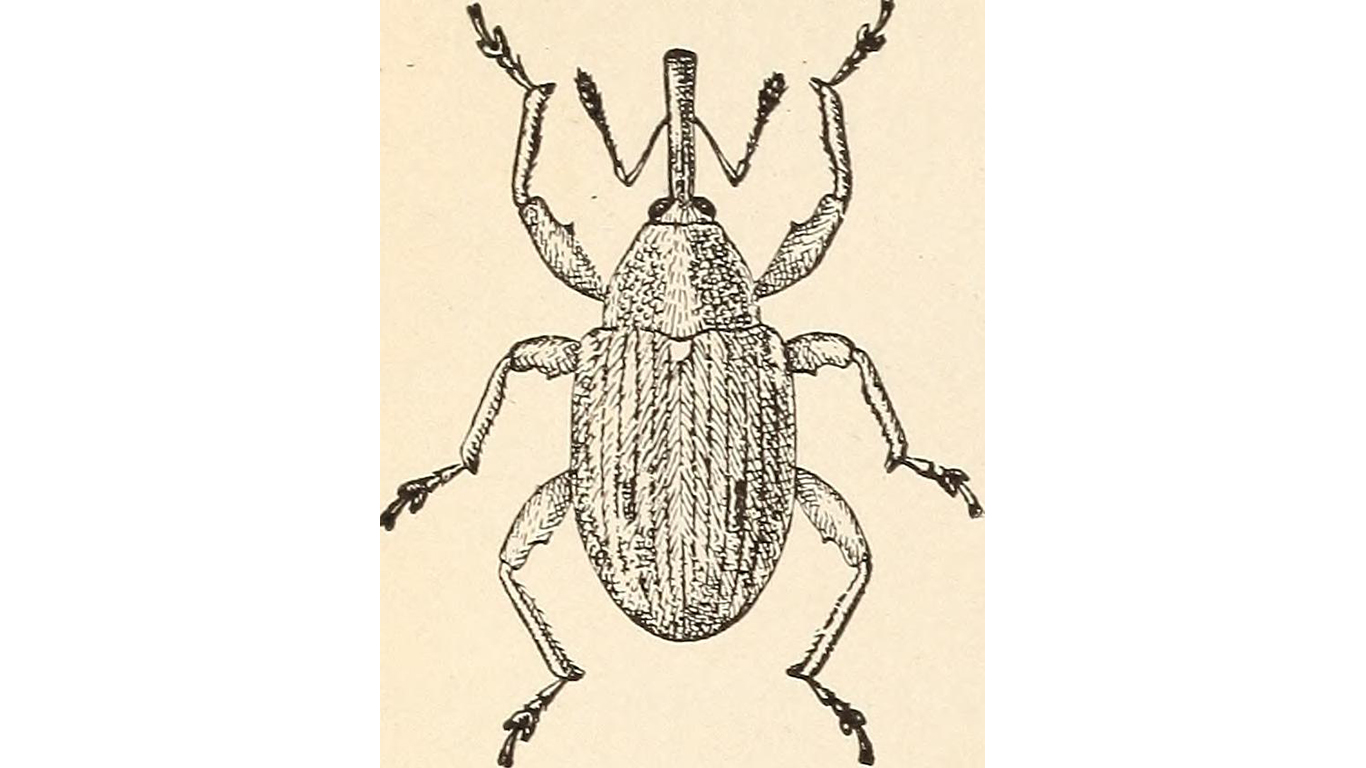

Boll weevil

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 1892

The boll weevil, a type of beetle which feeds almost solely on cotton plants, first appeared in the Southern United States in 1892 and caused devastating losses to the cotton industry throughout the first few decades of the 20th century. Five years after the beetle first appeared in the South, cotton production was already down 50%. The boll weevil is native to southern North America and Central America.

Silverleaf whitefly

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 1897

Possibly imported from India on ornamental plants, the silverleaf whitefly has caused $500 million in agricultural losses in California alone. The flies feed on over 500 agricultural crops, including cotton, melons, and cabbage. Nationwide losses due to whiteflies are estimated to exceed $1 billion.

Hemlock wooly adelgid

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 1920s

Eastern hemlocks are ecologically important trees due to the unique conditions they create for other plant and wildlife species. The hemlock wooly adelgid, an invasive species from Japan, feeds on hemlock trees, usually causing death within four to 10 years.

First discovered in the U.S. on the West Coast in the 1920s, these aphid-like insects have also spread along the East Coast from Georgia to Maine, and inland to western New York state. They kill 90% of the eastern hemlock that they infest.

Grasshoppers

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 1931

In the summer of 1931, swarms of grasshoppers devoured millions of acres of crops in the Midwest, causing significant damage in Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota, which were already experiencing a severe drought. The grasshoppers ate vegetation down to the ground, not even leaving corn stalks in the fields.

[in-text-ad-2]

Oriental fruit fly

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 1940s

Oriental fruit flies are native to many tropical areas in Asia. They were first found in the U.S. in Hawaii in the 1940s, and have since become established there. They are often detected in California and Florida, too, and prompt the establishment of quarantine and eradication programs. They have been found in nearly 500 kinds of fruit, but they often prefer avocados, papayas, and mangos, causing extensive damage to agricultural crops.

Formosan subterranean termite

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 1960s

One of the most destructive pests in the United States, Formosan subterranean termites cause over $1 billion in damage every year. Believed to be native to East Asia, they were first detected in the continental U.S. in the 1960s and are now established in at least nine Southern states and Hawaii. Colonies can contain several million termites and to date have been impossible to eradicate.

[in-text-ad]

Mosquitos

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 1980

With the floodwaters of Hurricane Allen creating perfect mosquito breeding grounds in August of 1980, Texas was overrun with billions of mosquitos. Swarms targeted local cattle and horse ranches, sucking so much blood of livestock that they killed 15 cattle in one night.

Gypsy moth

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 1981

In 1981, European gypsy moth caterpillars defoliated over 9 million acres of trees in the Northeastern United States, from Maryland to Maine. The larvae — not to be confused with tent caterpillars, which build large webs in trees — are known to eat over 300 different species of trees and shrubs.

Africanized bees

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 1990

In the 1950s, a Brazilian apiary began crossbreeding African honey bees with local honey bees. Multiple swarms escaped and began moving northward, eventually reaching Texas in 1990. These Africanized bees attack intruders much more rapidly and in larger numbers than domestic honey bees, and they have even been known to chase humans for a quarter mile. Hordes of these bees have killed about 1,000 humans, earning them the name “killer bees.”

[in-text-ad-2]

Asian longhorned beetle

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 1996

Native to China and Korea, the Asian longhorned beetle was first detected in 1996. The beetle is a threat to eastern hardwood forests as it can infest and feed on a dozen different species of hardwood trees, including maple, ash, and birch. These beetles are currently a threat in Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio, and have the potential to destroy millions of acres of hardwoods.

Signs of the beetle appear after 3 to 4 years after infestation. Trees are destroyed over the course of 10 to 15 years and do not recover or regenerate.

Bedbugs

> Year of swarm / US introduction: Early 2000s

A New York City bedbug infestation in the early 2000s struck fear into residents and travellers alike. The bugs spread from private apartments to movie theaters to workplaces and popular clothing stores. Extermination efforts and legislation enforcing inspection of rental properties finally curbed the infestation.

[in-text-ad]

Mormon cricket

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 2001, 2003

In 2001 and 2003, Mormon cricket swarms caused up to $25 million in damages to Utah crops. Technically a katydid, the Mormon cricket can cause not only crop damage, but also automobile accidents. As thick swarms cover roadways, they create a traffic hazard similar to ice.

Rasberry crazy ants

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 2002

Named after an exterminator who discovered these ants in Houston, Texas, Rasberry crazy ants (or tawny crazy ants), for reasons not known, are attracted to electrical equipment. They travel in swarms and chew through computers, televisions, water pumps, and electrical wiring. Crazy ants are thought to be of either Asian or African origin.

Emerald ash borer

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 2002

Native to Asia, the emerald ash borer was discovered in Michigan in 2002. The beetle has since spread to 34 more states and killed tens of millions of ash trees in North America. Ash trees are one of the more abundant and valuable trees on the continent, and this beetle has cost hundreds of millions of dollars as it destroyed trees in public, private, and industrial land.

[in-text-ad-2]

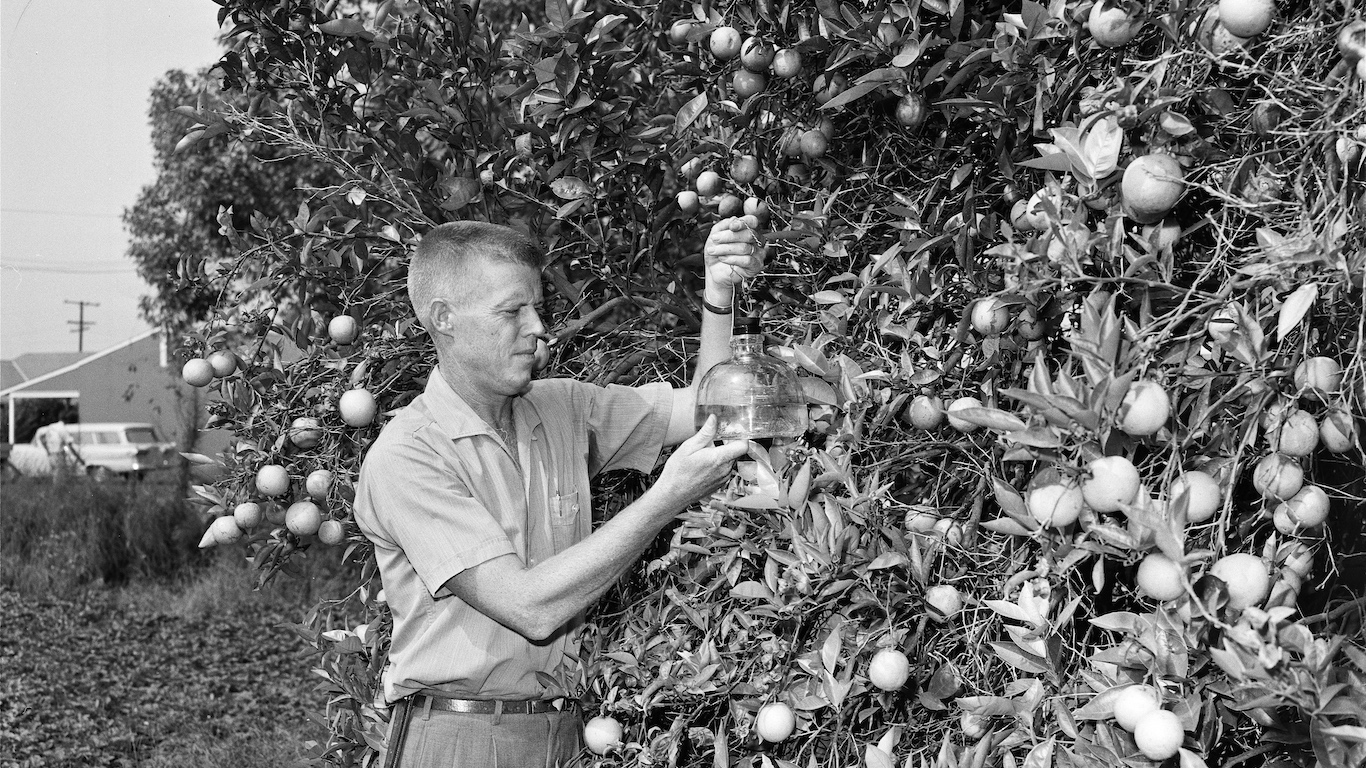

Citrus psyllid

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 2005

In a menacing partnership, a small insect and a bacterium have been ravaging Florida citrus groves since 2005. The citrus psyllid, a tiny invasive species originating in Asia, feeds on citrus leaves and spreads HLB, a disease that causes citrus greening. Once a tree is infected, it cannot be cured. The psyllids have evaded scientists by rapidly adapting to insecticides.

Spotted wing drosophila

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 2009

Drosophila, or fruit flies, are notoriously fast breeders that can proliferate 13 generations in a single growing season. While most fruit flies are attracted to overripe fruit, the spotted wing drosophila lays its eggs in underripe fruit, leading to maggot-infested crops.

The spotted wing fruit fly is believed to be native to eastern and southeastern Asia. First seen in the U.S. in 2009 on berries in California, these fruit flies have spread up the West Coast to Canada and can cause hundreds of millions of dollars worth of damage.

[in-text-ad]

Brown marmorated stink bug

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 2010

Also native to Asia but now present throughout much of the United States, brown marmorated stink bugs have been causing significant damage to fruit orchards and vegetable crops in the mid-Atlantic states and Pennsylvania since 2010. They have no natural predators in the area, and few approved pesticides are effective at controlling them.

Spotted lanternfly

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 2014

Native to northern China, the spotted lanternfly first appeared in Pennsylvania in 2014 and has spread to other mid-Atlantic states, triggering eradication efforts and quarantine zones. The flies can lay almost 200 eggs on a single host plant, and their sheer numbers overwhelm the vegetation. They are known to occupy over 70 host plant species, preferring grape and fruit trees. This infestation has affected specialty crop producers in the invaded area.

Grasshopper

> Year of swarm / US introduction: 2014

In 2014, the area around Albuquerque, New Mexico, became so densely infested with grasshoppers that the swarms were visible on radar. As the area was in drought and vegetation sparse, the grasshoppers moved to urban and suburban centers and damaged home lawns and gardens, also becoming a nuisance on roads and sidewalks.

Are You Still Paying With a Debit Card?

The average American spends $17,274 on debit cards a year, and it’s a HUGE mistake. First, debit cards don’t have the same fraud protections as credit cards. Once your money is gone, it’s gone. But more importantly you can actually get something back from this spending every time you swipe.

Issuers are handing out wild bonuses right now. With some you can earn up to 5% back on every purchase. That’s like getting a 5% discount on everything you buy!

Our top pick is kind of hard to imagine. Not only does it pay up to 5% back, it also includes a $200 cash back reward in the first six months, a 0% intro APR, and…. $0 annual fee. It’s quite literally free money for any one that uses a card regularly. Click here to learn more!

Flywheel Publishing has partnered with CardRatings to provide coverage of credit card products. Flywheel Publishing and CardRatings may receive a commission from card issuers.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.