The first historical reference to the Russian state was in 862, when it was known as Kievan Rus and ruled by Oleg of Novgorod. Since then, the country has fended off Mongol invaders, fought world wars, and seen its borders – and its sphere of influence – expand as Russia became the Soviet Union. After the breakup of the USSR in 1991, the country freed its satellite states and became the Russian Federation. (These were the republics of the Soviet Union.)

During most of its history, autocratic strongmen, whether emperors, empresses, or Communist Party leaders, controlled Russia and then the Soviet Union. Although some undertook reforms, they still continued to rule with an iron fist, not wanting to give up an inch of their power. Even if one leader made progress toward freedom, the succeeding ruler overturned many of those reforms. Alexander II freed the serfs, but was assassinated and replaced by his son, Alexander III, who quickly reversed many of his father’s enlightened policies. (These are the most ruthless leaders of all time.)

Eventually, the monarchs’ authoritarian domination led to a revolution and the rise of the Bolsheviks (Communists) into power. The Communists proved just as autocratic as the emperors in many ways. Although Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin sought a freer Russia, their successor – Vladimir Putin, in particular – returned the country to a virtual dictatorship. In February, Putin invaded Ukraine in an attempt to bring the independent country into Russia’s orbit once again as a step towards re-establishing the old Soviet Union.

To assemble a list of every Russian (and Soviet) head of state – and de facto ruler – since Peter I (known as Peter the Great) first took office as tsar 340 years ago, 24/7 Wall St. consulted lists of Russian and Soviet leaders on Britannica, History, Russia Beyond, and Wikipedia.

Click here to see every Russian (and Soviet) head of state since Peter the Great

During the Soviet era, the dates of several well-known leaders overlapped during their time in office. For example, Lenin and Stalin ran the country in turn in their capacity as chairman or first secretary of the Communist Party, even though they weren’t technically the titular heads of state. Other lesser-known figures held the official title of head of state, but were often relatively powerless.

Looking at Russia’s long history, perhaps it’s understandable why dictators like Putin remain firmly in power. Despite some brief forays in Western-style democracy, Russia’s roots are in authoritarian rule. Without a long-standing tradition of a free, democratic society, authoritarianism may continue to be Russia’s default government philosophy.

Peter I (the Great)

> Title: Tsar / Emperor

> In office: 1682-1696 (co-ruler with Ivan V), 1689-1721 / 1721-1725

Born in 1672 in Moscow, Peter I (Pyotr Alekseyevich in Russian) also known as Peter the Great, was the offspring of Tsar Alexis and his second wife, Natalay Kirillovna Naryshkina. In 1689, Peter won a fierce power battle with his half sister, Sofia, and took the throne. With an education that spanned both Russian and European history, Peter the Great is noted today for his military prowess and his integration of Russia into the modern European world.He preferred the title of Emperor, which he considered more European than Tsar. This led to some odd royal titles in the subsequent years. Male sovereigns continued to be called Tsar and their consorts, Tsarina or Tsaritsa, while female sovereigns took the title of Empress or its Russian form, Imperatritsa.

[in-text-ad]

Catherine I

> Title: Empress

> In office: 1725-1727

Catherine I, or Catherine the Great, was Peter the Great’s lover and later wife. Born Marta Skowronska, she later took the name Yekaterina (Catherine) Alekseyevna. Orphaned at age three, Catherine was raised by a Lutheran minister in what is now Latvia. When the Russians invaded Latvia in 1702, she was taken prisoner and subsequently met Peter I, whom she eventually married. The couple had 11 children, most of whom died in childhood. When Peter died in 1725 without naming an heir, Catherine assumed power. She had the support of several powerful individuals, who elevated her to the Empress of Russia. Not well educated, Catherine eschewed politics and let many of Peter’s domestic reforms slide.

Peter II

> Title: Emperor (Tsar)

> In office: 1727-1730

Before her death in 1727, Catherine appointed Peter’s grandson, Pyotr Alekseyevich, as her heir. Crowned at age 11, Peter II was placed under the tutelage of Aleksandr Menshikov, a close advisor to Peter I and Catherine I. Peter II didn’t like Menshikov’s overbearing nature, and soon teamed up with an aristocratic family, the Dolgorukys, who had Menshikov sent to Siberia. Yet for all the political maneuvering, Peter II’s reign was short, as he died at age 14 of smallpox.

Anna

> Title: Empress

> In office: 1730-1740

When Peter II died, the Supreme Privy Council offered the throne to Anna, the daughter of Tsar Ivan V and niece of Peter the Great. Made up of powerful nobles, the Council thought Anna would be easy to control as a figurehead. Although interested less in policy and more in courtly pleasures, Anna reigned as an autocratic empress, establishing a Secret Chancellery to investigate her perceived enemies. During her tenure, foreigners took many positions in the government, which was resented by Russians.

[in-text-ad-2]

Ivan VI

> Title: Emperor (Tsar)

> In office: 1740-1741

The son of Prince Anton Ulrich of Braunschweig-Bevern-Lüneburg and Anna Leopoldovna, the niece of Empress Anna, Ivan VI was named heir to the throne by his aunt, Empress Anna. The Duke of Courland, Ernst Johann Biron, a favorite of Empress Anna, became his regent. However, the Duke was soon overthrone and Ivan continued to reign with his mother as regent. Elizabeth, the daughter of Peter the Great, opposed Anna and deposed her. Ivan VI remained in solitary confinement for 20 years. A lieutenant named Vasily Yakovlevich Mirovich tried to wrestle the throne from Catherine II in 1762 and free Ivan VI. In the struggle to restore Ivan to the throne, he was assassinated by his jailers.

Elizabeth

> Title: Empress

> In office: 1741-1762

Said to have been beautiful and vivacious, Elizabeth was the daughter of Peter the Great and Catherine I. After staging a coup d’etat against Ivan VI and his mother, Elizabeth assumed the throne as Empress of Russia. During her reign, she restored some of her father’s reforms, but abolished others. Yet she supported education and the arts, founding Russia’s first university (in Moscow) and the Academy of Arts (in St. Petersburg). She also built the extravagant Winter Palace in St. Petersburg.

[in-text-ad]

Peter III

> Title: Emperor (Tsar)

> In office: 1762

The son of Anna, one of Peter I the Great’s daughters, and Duke Charles Frederick Herzog von Holstein-Gottorp, Peter III was named heir to the throne by his aunt Elizabeth. In 1745, he married Sophie Frederike Auguste, a German princess, who took the name Catherine. The marriage proved fateful, as Peter III’s pro-Prussian stance alienated many Russians, including his wife. Fearful he would divorce her, Catherine conspired with the guards and her lover to overthrow her husband. Peter III was later arrested and killed while Catherine II ascended to the throne.

Catherine II (the Great)

> Title: Empress

> In office: 1762-1796

The ambitious German-born Catherine II the Great advanced Peter the Great’s integration of Russia into Europe and expanded Russia into the Crimea and much of Poland. She is also famous for having had several lovers during her lifetime. After her husband, Peter III abdicated and was killed, Catherine rose to Empress with the title Catherine II. She reigned for 34 years and was known for dedication to the Russian people. However, her proposal to free the serfs was never enacted due to opposition from landowners.

Paul I

> Title: Emperor (Tsar)

> In office: 1796-1801

Son of Peter III and Catherine the Great, Paul I spent most of his youth away from the palace court. After he succeeded mother to the throne, Paul I solidified the power of the monarch by abolishing Peter the Great’s rule that each emperor could name his or her successor. Instead, he installed the male line of the Romanov family as sovereigns. Paul I so alienated the nobility with his strict autocratic policies that a cadre of civil and military officers conspired with his son, Alexander, to overthrow Paul I, who was assassinated in his bedchamber.

[in-text-ad-2]

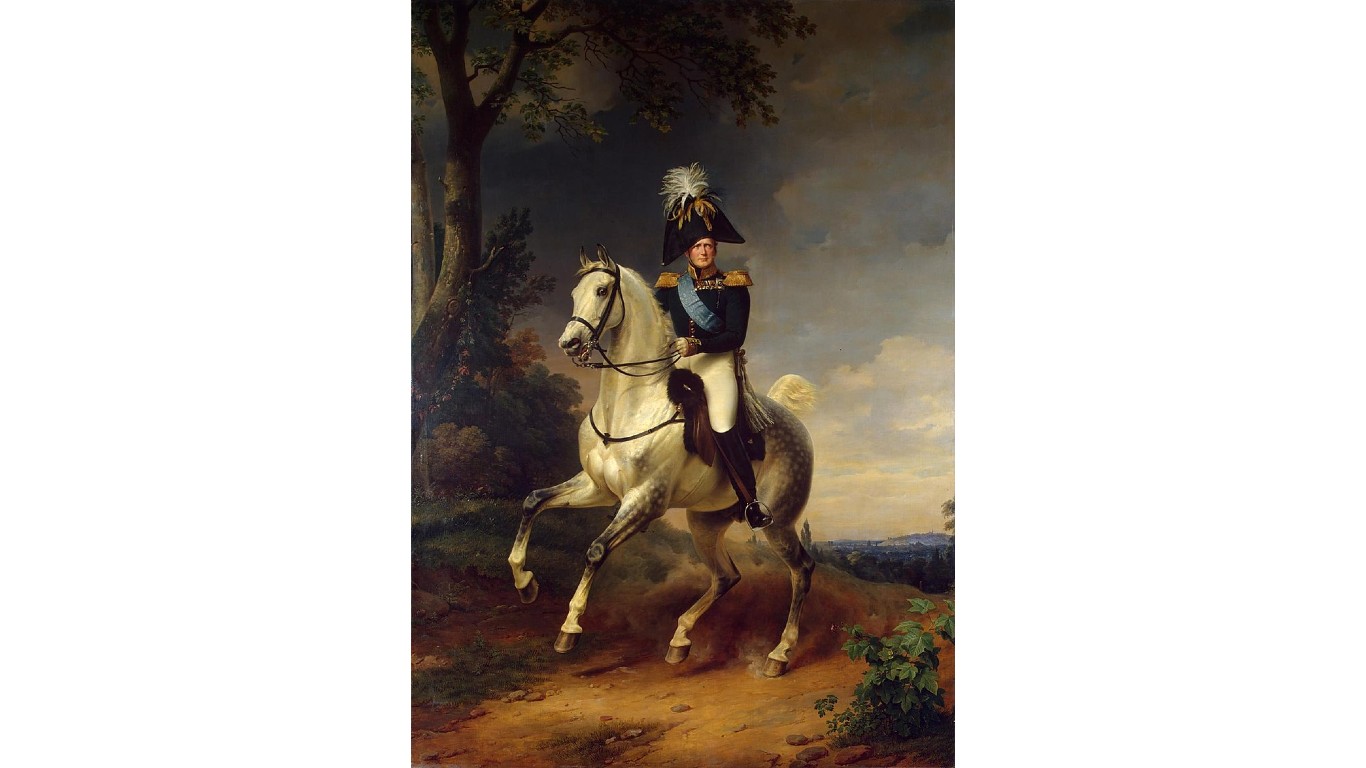

Alexander I (the Blessed)

> Title: Emperor (Tsar)

> In office: 1801-1825

Taking the throne following the death of his father, Paul I, Alexander I reversed some of his father’s harsh dictatorial policies, but did not abolish serfdom. During the Napoleonic Wars, Alexander I both opposed and befriended Napoleon, but eventually formed a coalition that defeated the French emperor. He died suddenly in 1825.

Constantine

> Title: Emperor (Tsar) (renounced the throne and never acceded to office)

> In office: 1825

Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich (Constantine) was the son of the Russian Emperor Paul I, younger brother of Alexander I, and elder brother of Nicholas I. From 1815 to 1830, he ruled the Kingdom of Poland. When Alexander I died in 1825, a fight over who would take the throne broke out between loyalists to Nicholas and a group of revolutionaries known as the Decembrists who supported Constantine. Constantine didn’t participate in the uprising, which was quickly quelled. Constantine and Nicholas disagreed over foreign policy, with Constantine believing the Polish army would be loyal to Russia. But when a revolution broke out in Warsaw in 1830, the army sided with the rebels. Constantine died of cholera in 1831.

[in-text-ad]

Nicholas I

> Title: Emperor (Tsar)

> In office: 1825-1855

The son of Emperor Paul I, Nicholas I (Nikolay Pavlovich) rose to become emperor because his eldest brother, Alexander I and Alexander’s wife, Elizabeth Alexeyevna, had no children. Another brother, Constantine, had renounced any claim to the throne. Nonetheless, revolutionaries supportive of Constantine started a rebellion, but were defeated. Nicholas took the throne after promising a constitution and civil liberties. However, in light of the rebellion, he became more autocratic and domineering. Yet he did support a measure to have landowners voluntarily free the serfs.

Alexander II (the Liberator)

> Title: Emperor (Tsar)

> In office: 1855-1881

Although upholding the authority of the tsars, Alexander II nevertheless freed the serfs and reformed many of the country’s antiquated laws. The son of Nicholas I, Alexander II attempted to move Russia into the industrial age then flourishing in Europe. In response to the country’s repression in 1866, a terrorist group, the People’s Will, rose up and advocated for a constitution. On the day he signed a proclamation supporting the constitution in 1881, Alexander was assassinated by bombs placed by People’s Will.

Alexander III (the Peacemaker)

> Title: Emperor (Tsar)

> In office: 1881-1894

Unlike his reform-minded father, Alexander III, who took the throne after his father’s death, opposed representative government and supported Russian nationalism. His reign was a period of peace for Russia, with Alexander loathing military conflict. It was also a period that saw Russia retreating into more conservative principles, such as censorship and limiting the role of universities. He died after a brief illness in 1894, leaving the throne to his son, Nicholas II.

[in-text-ad-2]

Nicholas II

> Title: Emperor (Tsar)

> In office: 1894-1917

The last tsar of Russia, Nicholas II was known for a reign marred by incompetence and uprisings. Although he agreed to the formation of a Duma, a representative assembly with power to enact laws, Nicholas II nevertheless whittled away at the legislative body’s powers. Russia’s disastrous entry to World War I led to the Russian Revolution that toppled the tsar. In 1918, he and his family were killed by the Bolsheviks.

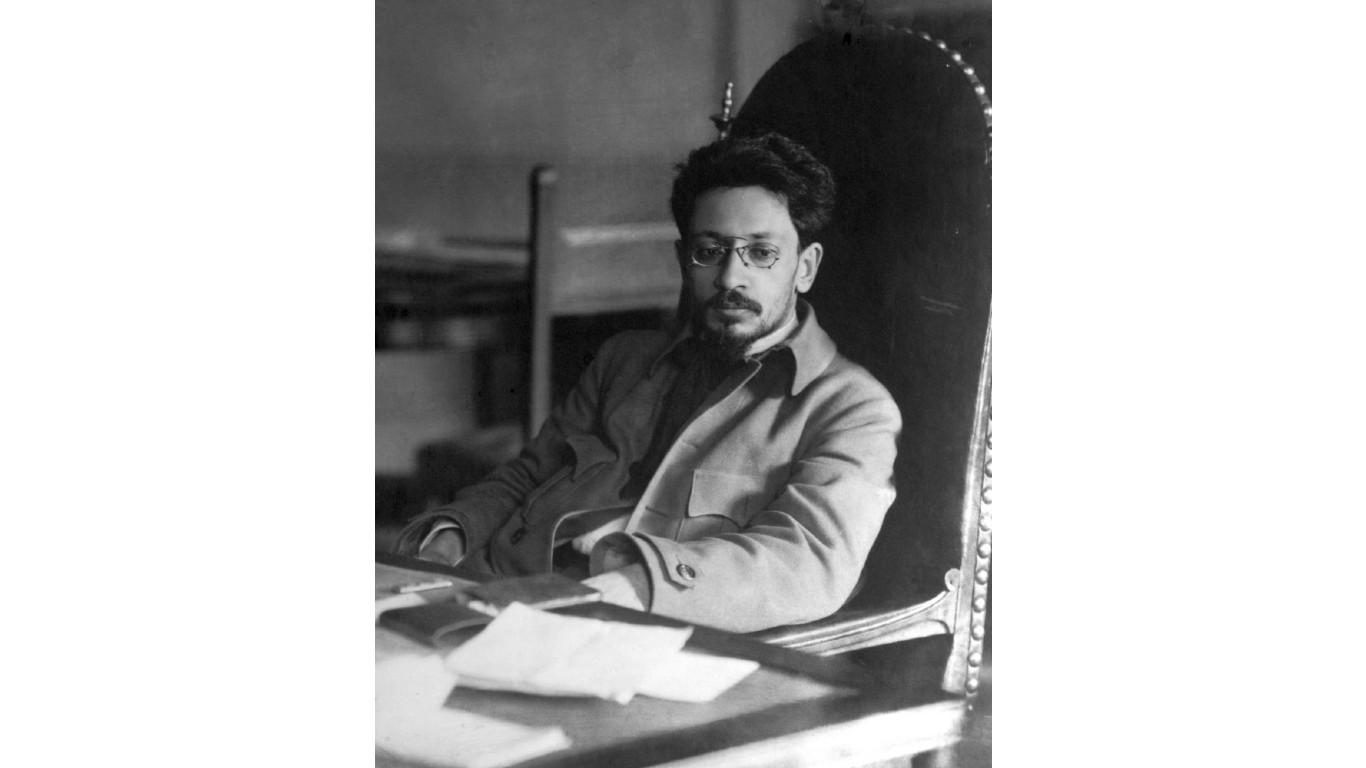

Lev Kamenev

> Title: Chairmen of the Central Executive Committee of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets

> In office: 1917

Lev Kamenev joined the Russian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party in 1901 and its Bolshevik arm in 1903. After the February Revolution in 1917, Kamenev served as the first chairman of the Central Executive Committee of All Russian Congress of Soviets and headed the Bolsheviks first Politburo. A one-time ally of Josef Stalin, Kamenev fell out of favor with Stalin and was later falsely accused of being a part in an assassination plot against him. In the hopes of saving his family, Kamenev confessed to the charges but was shot. The Soviet Supreme Court cleared him of charges in1988.

[in-text-ad]

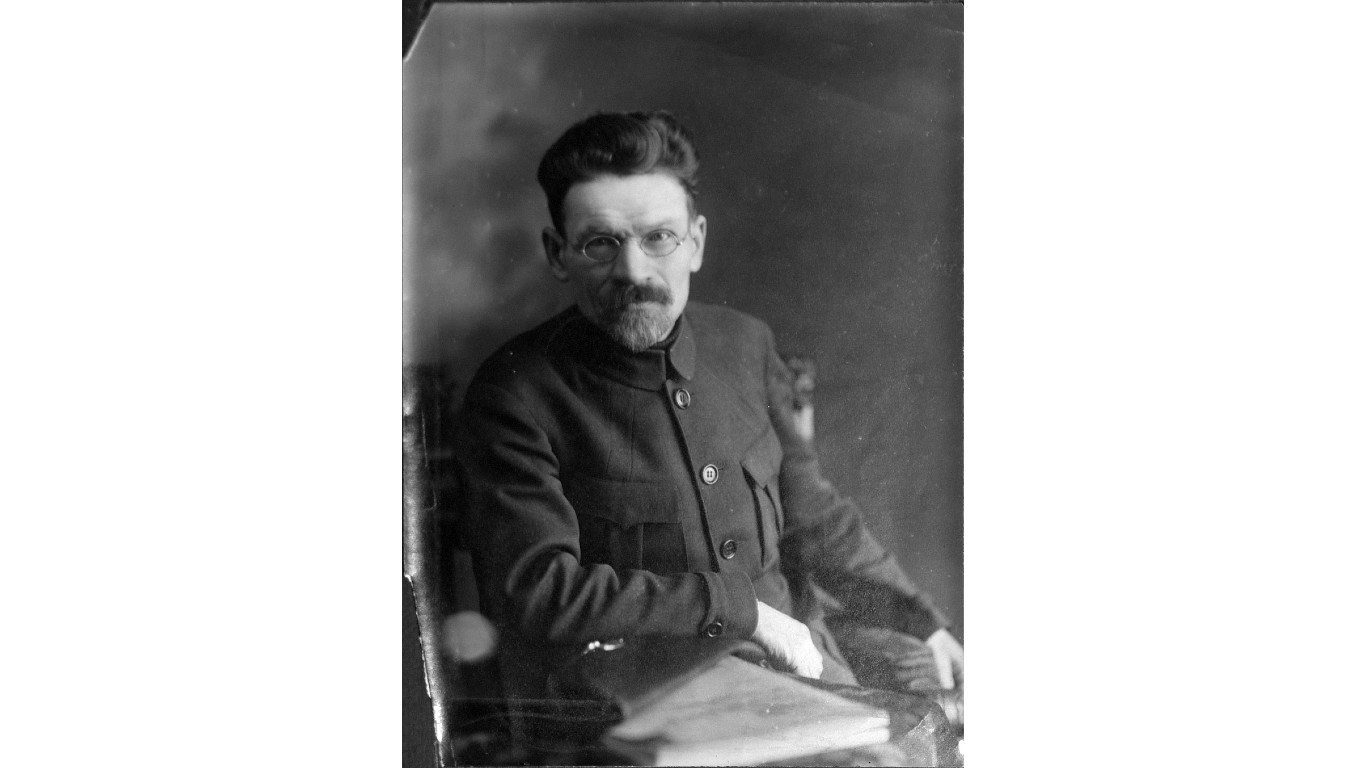

Yakov Sverdlov

> Title: Chairmen of the Central Executive Committee of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets

> In office: 1917-1919

Son of a Jewish engraver, Yakov Svedlov was active in the Bolshevik revolution from an early age. His organizational skills led to his election as chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the All Russian Congress, which elevated him to the titular head of the Bolshevik state. A close ally of Lenin, Svedlov believed in a centralized party hierarchy, with all decision-making concentrated in the Central Committee.

Michail Vladimirsky

> Title: Chairmen of the Central Executive Committee of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets

> In office: 1919

As a student at the Imperial Moscow University, Michail Vladimirsky agitated for Maxist reforms. He briefly left Russia for Switzerland, but returned to become Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the All-Russian Congress following the death of Yakov Sverdlow in 1919. He also served as chairman of the Gosplan (the State Committee for Planning) of the USSR from 1926 to 1927 and People’s Commissar of Public Healthcare of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic from 1930 to 1934. He supported Stalin against dissidents Leon Trotsky and Nikolai Bukharim.

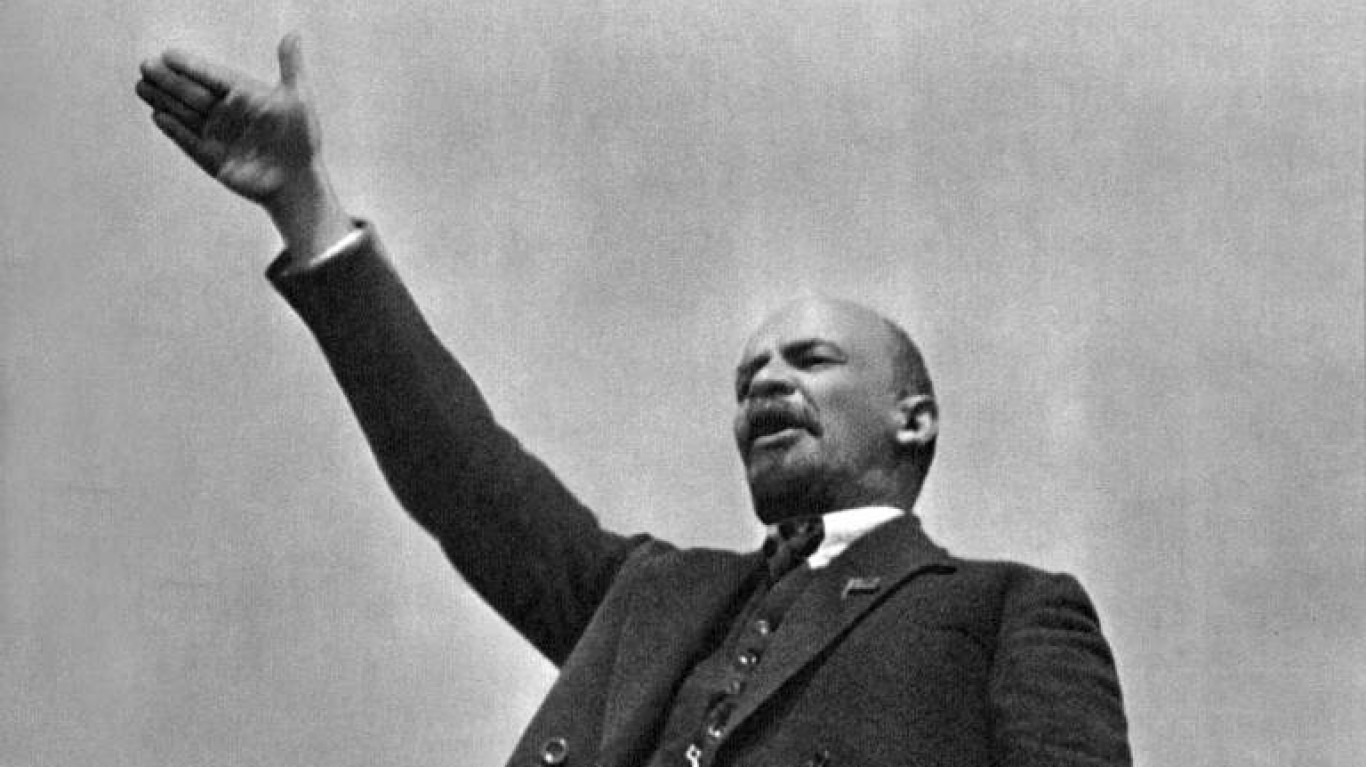

Vladimir Lenin

> Title: Chairman of the Council of the People’s Commissars of the Russian SFSR / Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Soviet Union

> In office: 1917-1923 / 1923-1924

Perhaps no leader has shaped Russia’s modern history more than Vladimir Lenin. He founded the Russian Communist Party (the Bolsehviks) and became the first head of the Soviet State. His inspiration for revolutionary politics was said to be the hanging of his brother, Alexandr, for allegedly trying to assassinate Tsar Alexander II. A strict follower of Marxism, Lenin started the revolution that deposed Nicholas II. After the revolution of 1917, Lenin oversaw a three-year civil war, during which he prohibited political opposition and nationalized all manufacturing and industry. Following an assassination attempt, Lenin began a campaign to execute his oppoents and followers of the former tsar. His death paved the way for Joseph Stalin, a man Lenin distrusted, to ascend to power.

[in-text-ad-2]

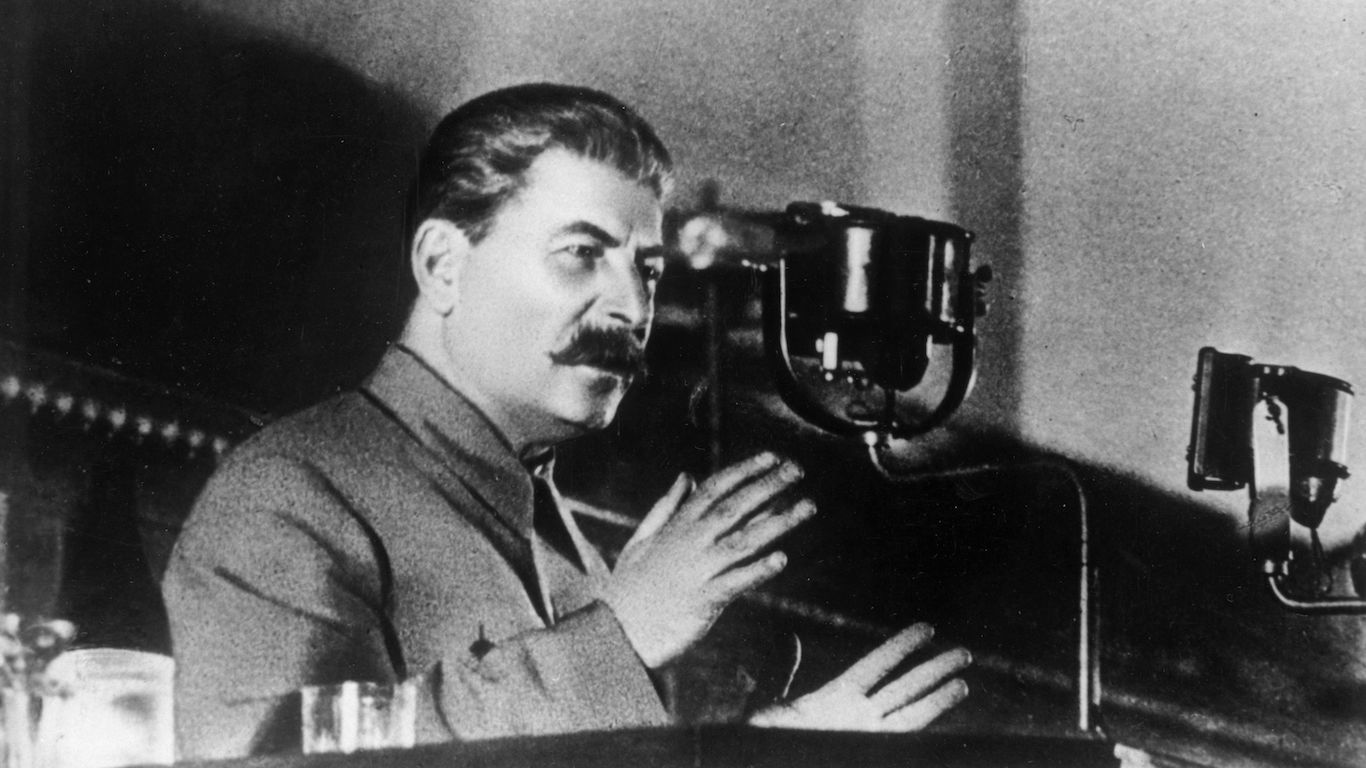

Joseph Stalin

> Title: General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union / Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union

> In office: 1922-1952 / 1946-1953

Although Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili, who rebranded himself as Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (inventing his last name based on “stal,” the Russian word for “steel”), led his country to victory in World War II, he is remembered today for a brutal totalitarian reign that reportedly killed 20 million citizen and silenced individual liberties. With an iron fist , he industrialized the nation, but also established a system of Gulag work camps where millions perished. He made the Soviet Union a nuclear power in 1949, and died of a stroke (though some scholars think he may have been poisoned) in 1953.

Nikita Khrushchev

> Title: General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union / Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union

> In office: 1953-1964 / 1958-1964

As Soviet premier from 1958 to 1964, Nikita Khrushchev led his country during the Cold War. Although he sought more peaceful relations with the West, Khruschev kicked off an international crisis when he attempted to place nuclear weapons in Cuba. Domestically, he instituted a “de-Stalinization” process to lighten the country’s previous restrictive policies. But he could be a brutal dictator, as well. He crushed a revolt in Hungary and approved the construction of the Berlin Wall. Party leaders withdrew their support for the premier after a war of words with China and food shortages at home, and he was forced to resign.

[in-text-ad]

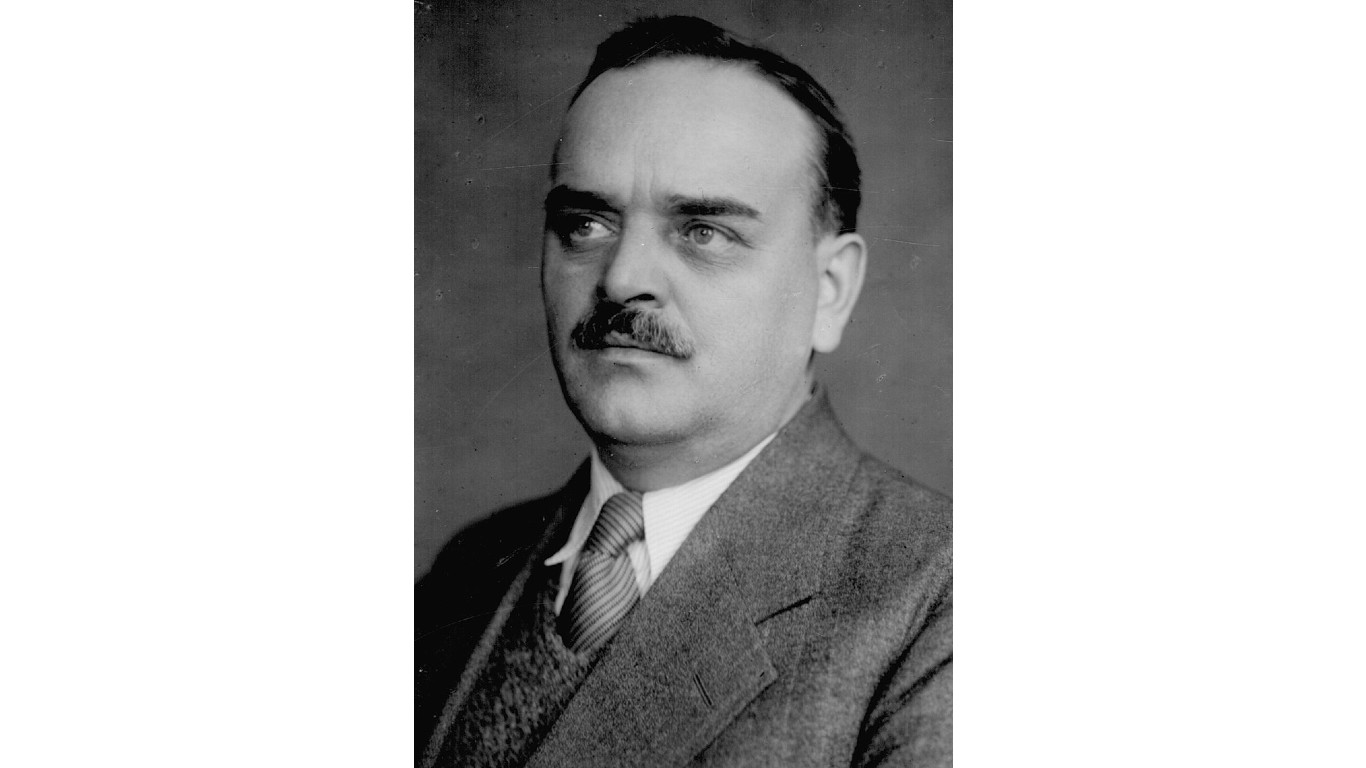

Georgy Malenkov

> Title: Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union

> In office: 1953

A close ally of Stalin, Georgy Malenkov assumed the post of chairman of the Ministers of the Soviet Union, or prime minister, after Stalin’s death. He was soon pushed aside by Nikita Khrushchev. In 1957, Malenkov was expelled from the Presidium (formerly the Politburo) and the Central Committee after he attempted to depose Khrushchev. During his time in politics, he tried to reduce arms appropriations, increase consumer goods production, and boost incentives for collective farm workers. In 1961, he was expelled from the Communist Party and went to work as a manager at a remote hydroelectric plant.

Mikhail Kalinin

> Title: Chairmen of the Central Executive Committee of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets / Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

> In office: 1919-1938 / 1938-1946

Mikhail Kalinin served as mayor of Petrograd (St. Petersburg) after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. Two years later, he rose to become head of the Soviet State as chairman of the central executive committee of the All-Russian Congress of the Soviets. From 1938 to 1946, he was named chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. A staunch follower of Stalin, Kalinin survived the dictator’s many purges during the 1930s.

Nikolay Shvernik

> Title: Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

> In office: 1946-1953

Nikolay Shvernik succeeded Mikhail Kalinin as chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. When Stalin died, he was removed as chairman and replaced by Kliment Voroshilov. His work with the Pospelov Commission in 1956 led Nikita Khrushchev to denounce Stalin and rehabilitate the victims of Stalin’s purges through the Shvernik Commission.

[in-text-ad-2]

Kliment Voroshilov

> Title: Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

> In office: 1953-1960

Kliment Voroshilov joined the Bolsheviks in 1903 and distinguished himself during the country’s civil war in 1917. During World War II, he held several military posts, but was unsuccessful in stopping the German advance. After the war, Voroshilov oversaw the communist party’s regime in Hungary. He became head of the Soviet state in 1953 following the death of Stalin.

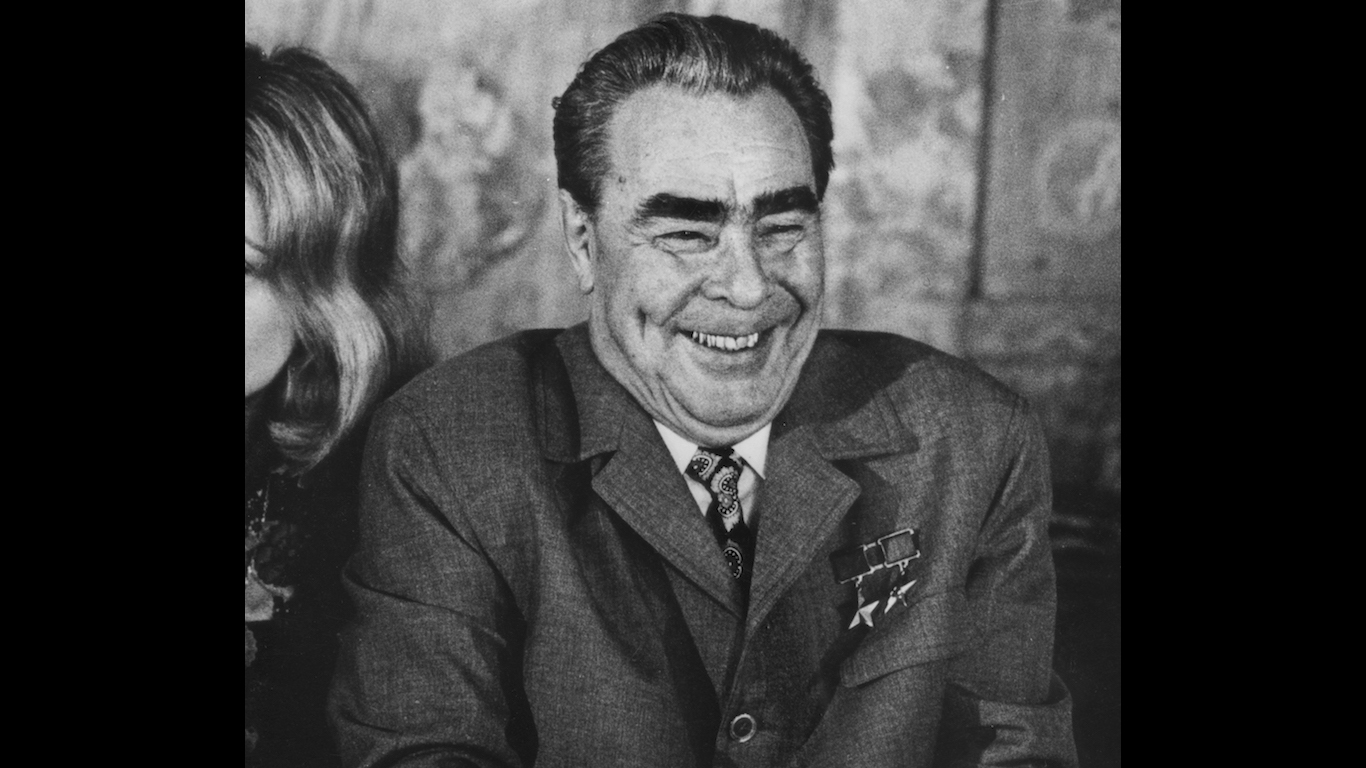

Leonid Brezhnev

> Title: Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

> In office: 1960-1964 / 1977-1982

A protege of Nikita Khrushchev, Leonid Brezhnev was first named president in 1960. The position wielded little political power, but gave Brezhnev the opportunity to meet with foreign officials. After Khrushchev was removed from office in 1964, Brezhnev took power, becoming the first person to lead both the Communist party and the state. In an effort to ease tensions with the U.S, Brezhnev established the policy of “detente.” Yet his regime was marked by brutal repression – he invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968 – and living standards at home stagnated as he favored building up the country’s military complex to the detriment of the rest of the economy.

[in-text-ad]

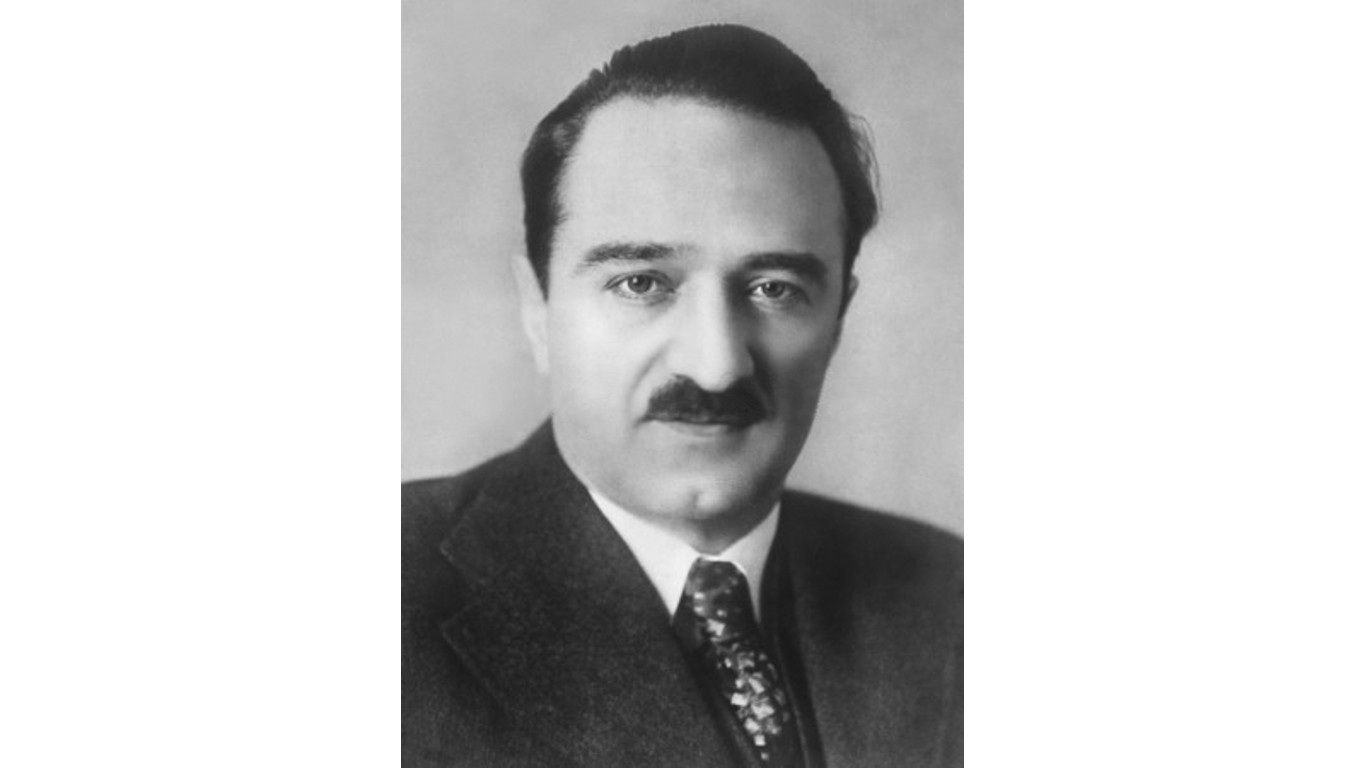

Anastas Mikoyan

> Title: Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

> In office: 1964-1965

An ally of Nikita Khrushchev, Anastas Mikoyan rose to the rank of first deputy premier of the Soviet Union. When Khrushchev was deposed, Mikoyan held the largely ceremonial title of chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from 1964 to 1965. Although he continued as a member of the Central Committee,after his death, he was buried in a cemetery in Moscow, not in the Kremlin wall reserved for high-ranking Soviet leaders.

Nikolai Podgorny

> Title: Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

> In office: 1965-1977

Ukrainian-born Nikolai Podgorny lost a power struggle with Leonid Brezhnev, then first secretary of the Communist Party, and was pushed into the less influential post of chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from 1965 to 1977. Because he opposed Brezhnev’s move to be named both party secretary and Presidium chairmanship, Podgorny was removed from the Politburo and relieved of his duties as chairman, with Brezhnev taking that position. He lived in retirement in Moscow following his ouster.

Vasili Kuznetsov

> Title: Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

> In office: 1982-1983 / 1984 / 1985

Before assuming the chairmanship of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, Vasili Kuznetsov served as ambassador to China for two years beginning in 1953. From 1955 to 1977, he was the first deputy minister of foreign affairs. After Leonid Brezhnev died in 1982, he ascended to the post of acting president of the Soviet Union until Yuri Andropov assumed that position in 1983.

[in-text-ad-2]

Yuri Andropov

> Title: Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

> In office: 1983-1984

As head of the Soviet Union’s KGB from 1967 to 1982, Yuri Andropov instituted a policy of suppression against the regime’s critics. A mere two days after Leonid Brezhnev’s death, he became president. Due to ill health, Andropov was rarely seen in public and didn’t accomplish anything of note during his time in office. He died after serving for 15 months.

Konstantin Chernenko

> Title: Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

> In office: 1984-1985

A hard-line conservative, Konstantin Chernenko was a close confidant of Leonid Brezhnev. After Brezhnev’s death, Chernenko was expected to take office, but lost out to his rival, Yuri Andropov. In 1964, following Andropov’s death, Chernenko assumed the post of general secretary of the Communist Party. Much as was the case with his predecessor, Chernenko’s tenure was brief due to failing health. He was succeeded by Mikhail Gorbachev.

[in-text-ad]

Andrei Gromyko

> Title: Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

> In office: 1985-1988

As Soviet foreign minister from 1957 to 1985, Andrei Gromyko was known to be a skilled negotiator with deep knowledge of international affairs. However, his impact on the country’s foreign policy is less clear. When Mikhail Gorbachev rose to the head of the Communist Party in 1985, Gromyko was removed as foreign minister and replaced by Eduard Shevardnadze. Gromyko then assumed the largely ceremonial position of president. In 1988, Gromyko resigned from his seat in the Politburo and the presidency of the Supreme Soviet as Gorbachev sought to reshape the Politburo.

Mikhail Gorbachev

> Title: Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet / Chairman of the Supreme Soviet / President of the Soviet Union

> In office: 1988-1989 / 1989-1990 / 1990-1991

Under Mikhail Gorbachev’s leadership, the Soviet Union began a new era of “glasnost” (openness) that led to a more open society with increased freedom of expression. His attempt to decentralize the country’s economy ultimately resulted in the downfall of the Soviet Union’s domination of Eastern Europe in 1991. He fought off a coup by hardliners, but his power was irrevocably weakened. In 1991, Gorbachev resigned as president of the Soviet Union and was replaced by Boris Yelstin.

Boris Yeltsin

> Title: President of the Russian Federation

> In office: 1991-1999

A dedicated reformer, Boris Yelstin won the first popular election for president in the country’s history in 1991. Although he moved the country’s economy toward free markets and private enterprise, he could nevertheless be a hardliner. When Chechnya declared its independence, he sent in troops to stop the rebellion. The latter days of his presidency were marked by the Chechnya crisis and economic troubles. He won election in 1996, but after suffering a heart attack he resigned his position in 1999, leading to the ascendency of Vladimir Putin.

[in-text-ad-2]

Vladimir Putin

> Title: President of the Russian Federation

> In office: 1999-2008 / 2012-

A former KGB agent, Vladimir Putin was named director of the Federal Security Service (the KGB’s successor) by Boris Yeltsin in 1998. The next year, Yeltsin tapped Putin as prime minister. That same year, he became president following Yeltsin’s resignation. Soon afterwards, Putin won the electoral vote due mostly to his successful efforts to keep Chechnya under Russian control. After his chosen successor, Dmitry Medvedev, was elected president in 2008, Putin was appointed prime minister. The two men agreed to trade positions after the 2012 election. During his time in office, Putin annexed the Ukrainian province of Crimea in 2014, and this year invaded Ukraine in a battle that still rages. Putin was reportedly enraged by the breakup of the old Soviet Union and seeks to reestablish the former country’s global dominance.

Dimitry Medvedev

> Title: President of the Russian Federation

> In office: 2008-2012

A close associate of Vladimir Putin, Dimitry Medvedev was elected president of the Russian Federation in 2008. He and Putin ruled the country virtually in tandem. After not running for president in 2012, Medvedev conceded the position to Putin, who named him prime minister that same year. During his time in office, he successfully integrated Russia into the World Trade Organization.

100 Million Americans Are Missing This Crucial Retirement Tool

The thought of burdening your family with a financial disaster is most Americans’ nightmare. However, recent studies show that over 100 million Americans still don’t have proper life insurance in the event they pass away.

Life insurance can bring peace of mind – ensuring your loved ones are safeguarded against unforeseen expenses and debts. With premiums often lower than expected and a variety of plans tailored to different life stages and health conditions, securing a policy is more accessible than ever.

A quick, no-obligation quote can provide valuable insight into what’s available and what might best suit your family’s needs. Life insurance is a simple step you can take today to help secure peace of mind for your loved ones tomorrow.

Click here to learn how to get a quote in just a few minutes.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.