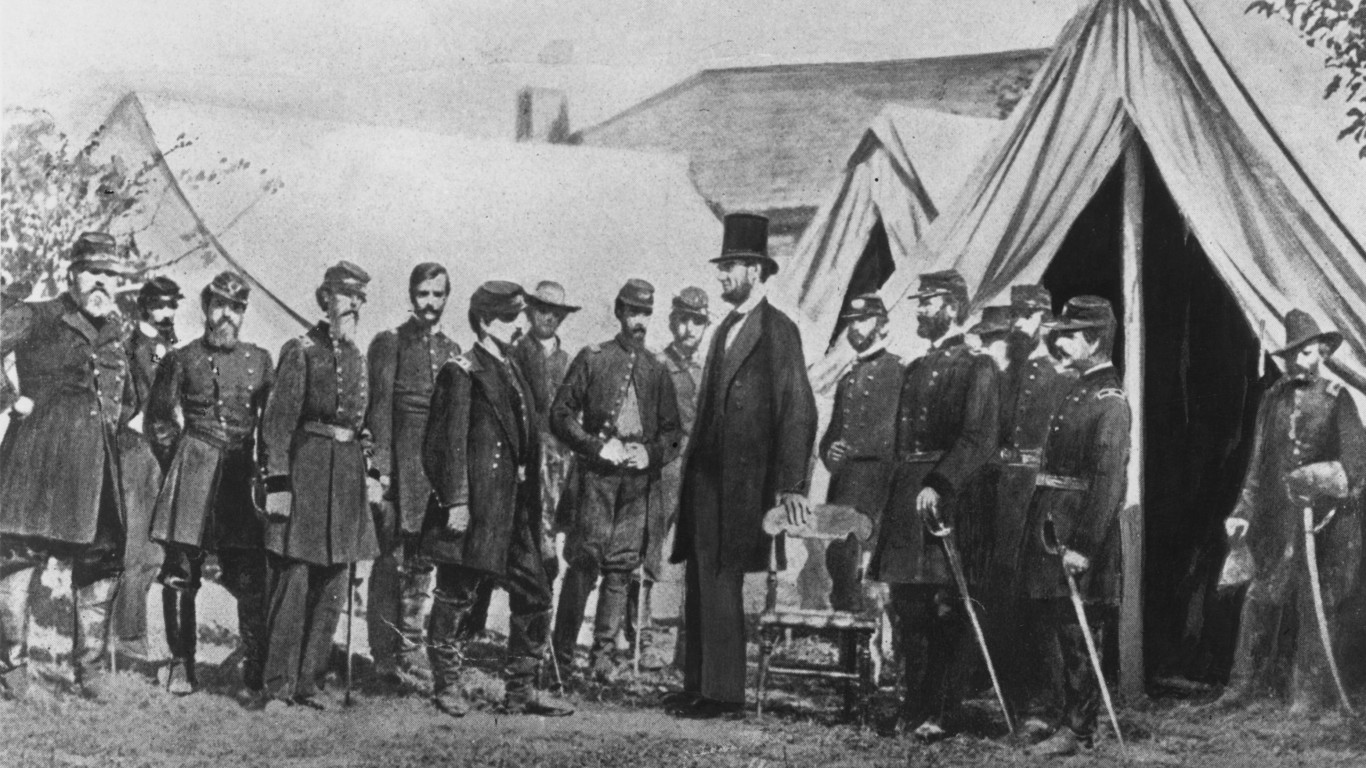

During the years preceding the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, often considered the start of the Civil War, the U.S. military was already busy building defensive fortifications around major cities. Often on seacoasts, these structures were commissioned to better protect the United States from foreign invasion after coastal defense systems proved ill-prepared during the War of 1812. (These are the oldest military forts built before America was a country.)

A budding war between the states hastened the construction of more forts, not only on coasts but also around key cities, supply lines, and transportation routes. Union forces built over 60 forts around Washington, D.C. alone, as neighboring states seceded (like Virginia) or held significant populations sympathetic to the Confederacy (as was the case with Maryland).

Brick or masonry forts were the standard before the war, but the advent of rifled cannons, which had significantly better range and destructive potential than the traditional smoothbore cannons, made masonry forts obsolete. This led to the construction of many earthwork forts, which were inexpensive, quick to build, and could absorb the impact of cannonballs better than masonry.

Although many forts of the era were destroyed during the war or deconstructed afterward, some have survived to this day. To determine 33 Civil War forts that you can visit, 24/7 Tempo compiled military fortifications that were used during the Civil War from sources including the National Park Service as well as state and regional tourism websites.

Click here to see 33 Civil War forts you can still visit

We focused on accessible sites that are open to the public. In many cases, the original forts have not survived intact, but in addition to some surviving structures, the sites may contain ruins, reconstructed facilities, or historically accurate replicas on the original fort grounds, as well as museums and reenactments. The list is not exhaustive.

Both masonry and earthworks forts are on the list. Some were built well before the Civil War, while others were built in haste during the war. Many sites remained in military use during subsequent wars and contain updated fortifications and weaponry; and a few are still in active use. Other sites were abandoned and have only been recovered and reconditioned during the 20th or 21st centuries. Most are parts of state or national parks, including National Historic Parks and National Battlefield Parks. (These were the largest battles of the Civil War.)

Fort Mifflin

> Location: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

> Built: 1771

The site of a Revolutionary War siege and later a Civil War prison, Fort Mifflin (also known as Mud Island) is a National Historic Landmark with educational programming and visiting hours from March 1 through December 15. Part of the fort’s grounds are still in use by the Army Corps of Engineers, making it the oldest military fort in use in the U.S.

[in-text-ad]

Fort Moultrie

> Location: Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina

> Built: 1776

Built on Sullivan’s Island, a defensive position outside of Charleston, Fort Moultrie was abandoned by Federal troops shortly after South Carolina seceded from the Union. It was taken over by the Confederates and, along with the better-known nearby Fort Sumter, heavily bombarded by Union fleets. Many of the fort’s buildings have been restored and are now part of a National Historic Park.

Fort Trumbull

> Location: New London, Connecticut

> Built: 1777

Used as a training center for Union troops, Fort Trumbull has been through multiple upgrades and rebuilds. The current masonry fort was built between 1839 and 1852 and is open to the public as part of a Connecticut State Park that offers tours and interactive exhibits.

Fort Jay

> Location: Governor’s Island, New York

> Built: 1794

Built to defend upper New York Bay, Fort Jay was used to house Confederate officer prisoners of war. Several Rodman guns – Civil War-era cannons – remain on site, and the well-preserved star-shaped fort lies protected within the Governor’s Island National Monument, whose grounds visitors can tour weekends.

[in-text-ad-2]

Fort Washington

> Location: Fort Washington, Maryland

> Built: 1808

Intended to defend Washington, D.C. from river approaches, Fort Washington was garrisoned by U.S. Marines during the Civil War. The current masonry structure, built in 1824, along with concrete artillery batteries built in the 1890s, is contained within the grounds of Fort Washington National Park and is open to the public daily.

Fort Delaware

> Location: Pea Patch Island, Delaware

> Built: 1817

Used as a prison for Confederate prisoners of war, Fort Delaware housed nearly 33,000 men during the conflict. It is now part of a living history museum where staff dressed in period clothing perform demonstrations. The pentagonal fort, surrounded by a moat, is located on an island accessible by a seasonal ferry.

[in-text-ad]

Fort Gaines

> Location: Dauphin Island, Alabama

> Built: 1821

Fort Gaines saw extensive fighting during the Battle of Mobile Bay, in which Union naval forces defeated the Confederate fleet and secured the bay. One of the best preserved Civil War masonry forts, the site features original tunnels, cannons, a blacksmith shop, and pre-Civil War buildings. However, storms and shore erosion threaten the future of the site.

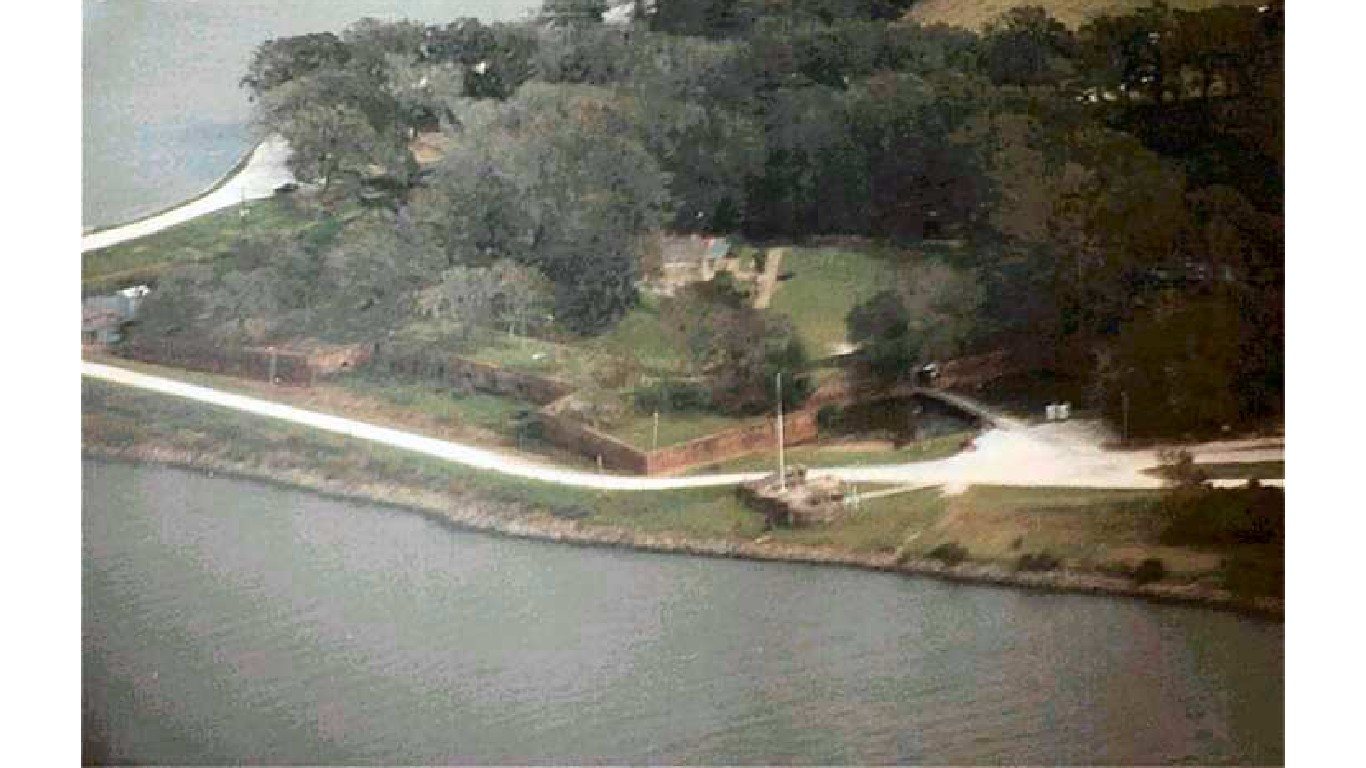

Fort Jackson

> Location: Buras, Louisiana

> Built: 1822

This star-shaped masonry fort was built to defend New Orleans. In 1862, it was besieged for 12 days and hit with several thousand cannon shots until Union forces were able to advance past it and capture New Orleans. Afterward, it served as a Union prison. The current fort’s interior is closed to the public due to hurricane damage but the grounds and exterior are accessible and the nearby Fort Jackson Museum contains historical artifacts and exhibits.

Fort Pulaski

> Location: Cockspur Island, Georgia

> Built: 1829

Built between 1829 and 1847 for the defense of Savannah, Fort Pulaski was seized by Confederate troops in 1860. In 1862, Union forces utilized new artillery technology to bombard the fort, causing massive damage and leading the Confederate colonel in charge to surrender. The pentagonal fort is now a national monument revealing some of the original artillery damage.

[in-text-ad-2]

Fort Sumter

> Location: Charleston, South Carolina

> Built: 1829

The construction of Fort Sumter was initiated in 1829 but was incomplete when the South Carolina militia began bombarding it in 1861, initiating the Civil War. It was heavily damaged by Union artillery during the Siege of Charleston Harbor and reduced to a heap of rubble. After the war, the walls were partially rebuilt and now the fort is part of the Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historic Park, accessible by ferry.

Fort Independence

> Location: Castle Island, Massachusetts

> Built: 1833

Formerly known as Castle William, this fort sits in a defensive position in Boston Harbor. Although the site has been fortified since 1634, the current buildings date to 1833-1851, and were used to train Union soldiers. Fort Independence is now a popular State Park, offering visitors free tours during the summer.

[in-text-ad]

Fort Warren

> Location: Georges Island, Massachusetts

> Built: 1833

Located near the mouth of Boston Harbor, Fort Warren is a star-shaped stone and granite fort built between 1833 and 1861. It served as a prison for Confederate officers and other political prisoners, and was in active military use until 1947. The impressive military base and a conjoined museum are accessible by ferry or private boat as a part of the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area.

Fort Schuyler

> Location: Bronx, New York

> Built: 1833

Constructed to protect New York City’s eastern waterways, Fort Schulyer was garrisoned in 1861 and was used as a prison, hospital, and training center during the war. Abandoned in the 1920s, the fort later became the site of the New York State Merchant Marine Academy. The restored fort remains a school to this day, and also contains a maritime museum.

Fort Morgan

> Location: Gulf Shores, Alabama

> Built: 1834

This pentagonal bastion fort was captured by Confederates days before Alabama seceded from the Union, and was used extensively during the war to protect merchant ships evading a blockade at Mobile Bay, before it fell into Union hands. The fort has sustained hurricane damage in recent years, but is open daily for tours.

[in-text-ad-2]

Fort Pickens

> Location: Santa Rosa Island, Florida

> Built: 1834

One of very few Southern fortifications that was occupied by the Union during the entirety of the Civil War, Fort Pickens faced multiple battles and bombardments. It was updated during both world wars and, along with a military museum, is now a part of the Gulf Islands National Seashore, open to visitors.

Fort Barrancas

> Location: Pensacola, Florida

> Built: 1839

Months before the start of the Civil War, U.S. troops stationed at Fort Barrancas abandoned the post and moved just across the water to the more easily defendable Fort Pickens. Fort Barrancas was then briefly garrisoned by Confederate forces before it was again abandoned in May of 1862. The well-preserved buildings and visitors center are located on the Naval Air Station Pensacola.

[in-text-ad]

Fort Zachary Taylor

> Location: Key West, Florida

> Built: 1845

At the southwest tip of Key West, Fort Zachary Taylor was held by the Union during the Civil War and used to launch offensives on blockade-running merchant ships. The fort was used extensively in subsequent wars and is now a state park and National Historic Monument that features a large cache of weapons and hosts Civil War reenactments.

Fort Jefferson

> Location: Garden Key, Florida

> Built: 1846

Although it was never finished, this fort in the lower Florida Keys is a massive structure covering 16 acres. It was garrisoned by Federal forces during the Civil War and used as a prison, largely for Union deserters. The impressive remains are a part of Dry Tortugas National Park, which is accessible by ferry, boat (personal or chartered), or seaplane.

Fort Clinch

> Location: Amelia Island, Florida

> Built: 1847

Seized by Confederates in 1861, this fort northeast of Jacksonville was used as a base for blockade-running ships before it was abandoned and re-taken by Federal troops. During the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps restored the fort to its Civil War-era condition and Fort Clinch State Park opened in 1938. Currently, living history demonstrations and reenactments draw visitors to the park.

[in-text-ad-2]

Fort Tompkins

> Location: Staten Island, New York

> Built: 1847

Built to guard New York City against land approaches from the west, this fort on Staten Island was used to house and train soldiers during the Civil War, but never saw battle. It remains very much intact, and is currently part of the Fort Wadsworth National Recreation Area. Visitors can no longer enter the fort, but the grounds offer views of the historic structures and many batteries remain open.

Fort Massachusetts

> Location: Ship Island, Mississippi

> Built: 1859

Located on a Gulf Coast island, this fort was seized by Mississippi militia members in January 1861, but eventually abandoned. Union forces then took over the island and stationed troops there who would go on to capture New Orleans. Due to the harsh environment, many soldiers died while stationed at Fort Massachusetts. Now maintained as part of the Gulf Islands National Seashore, the fort is accessible by ferry and tours run from spring to fall.

[in-text-ad]

Fort Popham

> Location: Phippsburg, Maine

> Built: 1861

This granite fort at the mouth of the Kennebeck river was constructed to protect Augusta from a possible Confederate invasion. The fort was never completed, as new weapons technology, namely the rifled cannon, propelled masonry forts into obsolescence. Now a State Historic Site, Fort Popham is a popular area with tourists and photographers.

Fort Ward

> Location: Alexandria, Virginia

> Built: 1861

One of many forts built to defend Washington, D.C., Fort Ward never saw battle and was eventually abandoned and deconstructed; however its earthworks remained intact for over a century. In 1962, the city of Alexandria began an archaeological restoration that rebuilt the northwest bastion. The fort grounds now feature replicated cannons, reenactments, and a Civil War museum.

Fort Rodman

> Location: New Bedford, Massachusetts

> Built: 1861

Construction of Fort Rodman began in 1857, but by the time of the Civil War, it was nowhere near completion, and a nearby earthwork fort (Fort Taber) was built in the meantime. The fort complex never saw battle. The area is currently open to the public as Fort Taber Park, but the structure at Fort Rodman is awaiting renovation before the interior is open to the public. A military museum on site offers exhibits and reenactments.

[in-text-ad-2]

Fort Totten

> Location: Queens, New York

> Built: 1862

Located at the head of Little Neck Bay, this fort was designed in part by Robert E. Lee. The original plans were never completed, but subsequent wars saw many additions to the fortifications. Fort Totten is currently a park maintained by the city, where visitors can tour the fortress and other historic buildings.

Fort Negley

> Location: Nashville, Tennessee

> Built: 1862

Constructed largely by runaway slaves who flocked to Nashville after Union forces took over the city, Fort Negley never ended up seeing battle, and was abandoned after the war. Significant ruins of the fort have been restored and a visitors center offers educational programming. During archaeological analysis, unmarked graves thought to be those of buried slave laborers were uncovered on the grounds, halting planned redevelopment of a vacant on-site stadium.

[in-text-ad]

Fort Donelson

> Location: Dover, Tennessee

> Built: 1862

Soon after it was built by Confederate forces in 1862, Fort Donelson was captured by the Union Army under General Ulysses S. Grant, and remained in their power for the remainder of the war. It is now a part of Fort Donelson National Battlefield Park, which contains both ruins and rebuilt areas, and includes the nearby Fort Heiman.

Fort Pocahontas

> Location: Charles City, Virginia

> Built: 1864

The site of the Battle of Wilson’s Wharf, a skirmish between the Army of Northern Virginia and the 1st and 10th U.S Colored Troops (USCT) – regiments of mainly African-American soldiers – this fort site contains intact earthworks built by the USCT. Fort Pocahontas became a refuge for runaway slaves until its abandonment in 1865. The site is now on the National Register of Historic Places and offers occasional historical reenactments.

Fort Monroe

> Location: Hampton, Virginia

> Built: 1819

The largest fort by area ever built in the United States, Fort Monroe was constructed to protect the Chesapeake Bay after the War of 1812. Confederate president Jefferson Davis was imprisoned there for two years beginning in May 1865. The fort remained in active use until 2011, when portions of the grounds were declared a national monument.

[in-text-ad-2]

Fort McHenry

> Location: Baltimore, Maryland

> Built: 1798

Built to protect Baltimore Harbor, Fort McHenry saw continuous use until World War I. During the Civil War, it housed Confederate soldier prisoners of war, as well as Confederate sympathizers. The grounds were made a National Park in 1925, and the fort is now a National Historic Monument open to the public daily.

Fort McAllister

> Location: Richmond Hill, Georgia

> Built: 1861

One of three forts defending Savannah, Fort McAllister was the site of numerous Civil War battles. It was finally overtaken by Union infantry under General William B. Hazen, allowing General William T. Sherman to capture the city. The fort has been restored to its 1864 appearance and is now part of the Fort McAllister State Historic Park.

[in-text-ad]

Fort Lytle

> Location: Bowling Green, Kentucky

> Built: 1861

Named Fort Vinegar when the Confederate Army built it in 1861, this fort is one of eight constructed around Bowling Green to protect supply lines from Nashville to Louisville. It was abandoned and subsequently taken over by Union troops in February 1861. The stone ruins and trenches are currently visible on the campus of Western Kentucky University.

Fort Pillow

> Location: Henning, Tennessee

> Built: 1861

Currently a State Historic Park, Fort Pillow was the site of the Fort Pillow Massacre, in which Confederate troops under the command of General Nathan Bedford Forrest killed 300 African-American soldiers after they surrendered, rather than taking them as prisoners of war. Parts of the inner fort have been reconstructed and a museum on site is open daily.

Travel Cards Are Getting Too Good To Ignore

Credit card companies are pulling out all the stops, with the issuers are offering insane travel rewards and perks.

We’re talking huge sign-up bonuses, points on every purchase, and benefits like lounge access, travel credits, and free hotel nights. For travelers, these rewards can add up to thousands of dollars in flights, upgrades, and luxury experiences every year.

It’s like getting paid to travel — and it’s available to qualified borrowers who know where to look.

We’ve rounded up some of the best travel credit cards on the market. Click here to see the list. Don’t miss these offers — they won’t be this good forever.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.