Serendipity refers to accidental discoveries that lead to beneficial outcomes. The word was coined in 1754 by Horace Walpole, inspired by a tale about three princes who made fortunate discoveries by chance rather than design.

Unexpected findings are common in scientific research. For instance, Teflon and Scotchgard were invented when chemists were trying to make something different. The woman who created Scotchgard was one of many female inventors behind key innovations.

According to biochemist Isaac Asimov, the most exciting phrase in science is not “Eureka!” but “That’s funny.” Alexander Fleming uttered the latter when mold contaminated his lab samples, leading to the discovery of penicillin, the first widely used antibiotic.

24/7 Tempo has compiled 31 accidental discoveries that changed the world by reviewing sources including History, Reader’s Digest, and Business Insider. In some cases, an initial accidental discovery by one person led to a later invention by another. Only the initial discovery is recounted.

While a few examples are based on folklore, most come from the work of scientists, engineers, doctors, and inventors who stumbled upon something while pursuing another goal.

Such happy accidents have revolutionized medicine and pharmacology. They have also influenced fashion, cosmetics, appliances, and toys. Some serendipitous discoveries have greatly improved daily life. (Here are also 30 NASA inventions we still use everyday.)

Click here to see the accidental discoveries that changed the world

Quinine

>Year: unknown

Before Jesuit priests introduced the malaria treatment quinine to Europe in the 17th century, they learned of its properties from indigenous Andean peoples. According to Andean legend, a man delirious with malaria was lost in the rainforest and drank bitter-tasting water from a puddle under some quina-quina (cinchona) trees. The tree had been previously considered to be poisonous, but the man’s fever soon abated and his people began using the tree bark to treat fevers. Andean people likely taught it to Jesuit priests.

[in-text-ad]

Brandy

>Year: 16th century

According to folk accounts, brandy was invented when a Dutch ship captain, who wanted to ship higher quantities of wine, decided to concentrate wine by removing the water before transport. Although his intention was to water it down again at his destination port, he liked the concentrated wine so much that he kept it that way, calling it brandewijn, meaning “burnt wine.”

Matches

>Year: 1826

A British pharmacist named John Walker was actually working on a paste that might be used in guns. He stirred chemicals with a wooden stick, and when he tried to scrape off the dried substance on the stick, it caught fire. Walker soon began marketing these fire-starting “friction lights,” which he packaged in a box with a strip of sandpaper for scraping.

Vulcanized rubber

>Year: 1839

Although natural rubber was a popular substance used in bootmaking in the 1830s, it could not handle temperature extremes, either cracking when frozen or melting when heated. Chemist Charles Goodyear was conducting experiments with rubber, which he began mixing with sulfur to make it less sticky, when he accidentally dropped some on a hot stove. Rather than melting, it charred into a sturdy, heat-resistant substance soon to be known as vulcanized rubber.

[in-text-ad-2]

Anesthesia

>Year: 1844

Although the psychoactive properties of nitrous oxide were discovered in the 1770s, the gas was almost exclusively used as a party drug amongst the British elite until the next century. In 1844, a dentist named Horace Wells attended a demonstration on the effects of the gas and noticed something interesting: a man who had bruised his legs while jumping around under the influence of nitrous had no idea that he’d hurt himself, and had felt no pain. Wells began using the drug in his dental practice, only after experimenting on himself by inhaling nitrous and having his own tooth pulled.

Mauve

>Year: 1856

While attempting to synthesize an artificial quinine from coal tar for the treatment of malaria, an 18-year-old chemistry student named William Perkin accidentally invented a purple pigment that could dye silk. Abandoning his pharmaceutical aspirations, Perkin named his color mauve after a French flower and established one of the first synthetic dye factories in the world, using his new aniline (an organic compound) dyes. His discovery revolutionized the fashion world and brought bright colors – which were previously very costly to create – to the middle classes.

[in-text-ad]

Vaseline

>Year: 1859

The chemist Robert Chesebrough got his start clarifying kerosene from whale fat, but his job was rendered obsolete when petroleum was discovered in Titusville, Pennsylvania. Intent on experimenting with the new crude oil, Chesebrough traveled to the oil fields, where he heard workers complaining about “rod wax,” a troublesome, jelly-like buildup that repeatedly clogged their pump equipment. When some of the workers claimed that the jelly healed their cuts, Chesebrough began refining it and eventually patented petroleum jelly, which he named Vaseline.

Chewing gum

>Year: 1870

There’s evidence of ancient Greeks and Scandinavians chewing on tree bark. Ancient Mesoamericans chewed a boiled tree sap called chicle, which is what modern-day chewing gum is derived from. In the 1850s, exiled Mexican president Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna approached inventor Thomas Adams in New York City with a cache of chicle and a plan to get rich selling tires. Adams attempted to vulcanize the chicle like rubber, but to no avail, instead using the chicle to create chewing gum, marketed as Chicklets.

Saccharin

>Year: 1879

While working under laboratory professor Ira Remsen at Johns Hopkins University, postdoctoral researcher Constantin Fahlberg was conducting experiments with coal tar. One evening, he noticed his dinner tasted particularly sweet, and then realized he hadn’t washed his hands after work. Fahlberg and Remsen found the sweet substance in the lab and published their chemical discovery of this artificial sweetener in 1880. Fahlberg subsequently patented the substance, which he called “saccharin.”

[in-text-ad-2]

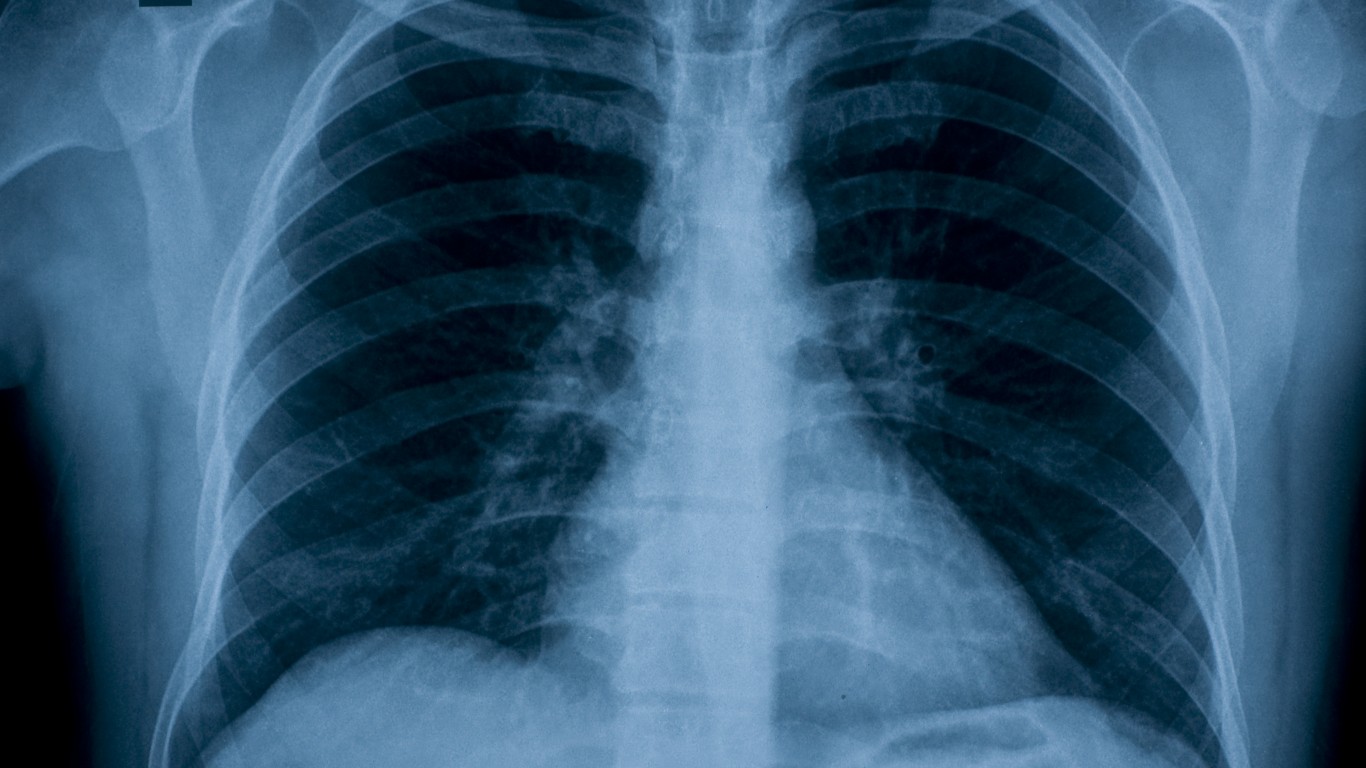

X-Ray

>Year: 1895

While replicating a previously performed experiment with a cathode ray tube covered by an aluminum window and a piece of cardboard, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen noticed a green, glowing light on a piece of paper in the room. Knowing that cathode rays could not travel so far, especially through cardboard, he named the unknown rays X-radiation, and began testing materials that the rays could penetrate. While holding a piece of lead, Röntgen inadvertently saw the first radiographic image: his own skeleton hand. He proceeded to capture images on photographic plates, creating the first X-ray photographs.

Radioactivity

>Year: 1896

French physicist Henri Becquerel frequently experimented with phosphorescence and light absorption by crystals. When X-rays were discovered, he began conducting experiments to find a connection between X-rays and phosphorescence. While working with uranium crystals – which he believed would absorb energy from the sun and then burn an X-ray image onto a photographic plate – Becquerel accidentally discovered radioactivity.

One day as clouds rolled in, he packed up his uranium and plates, deciding to resume when it was sunnier. But the uranium still burned an image onto one of the plates. He concluded that the rays had not come from the sun, but from the uranium itself.

[in-text-ad]

Cornflakes

>Year: 1898

While working on a recipe for healthy, whole grain breakfast biscuits, brothers John and Will Kellogg produced a biscuit so hard that it broke someone’s tooth. They solved this problem by smashing the biscuits into pieces before serving them. One night, they accidentally left a pot of biscuit mixture out. It fermented, creating a pliable dough that rolled out more thinly than ever and baked into delicately crispy pieces. This new fermented recipe would be the precursor to cornflakes.

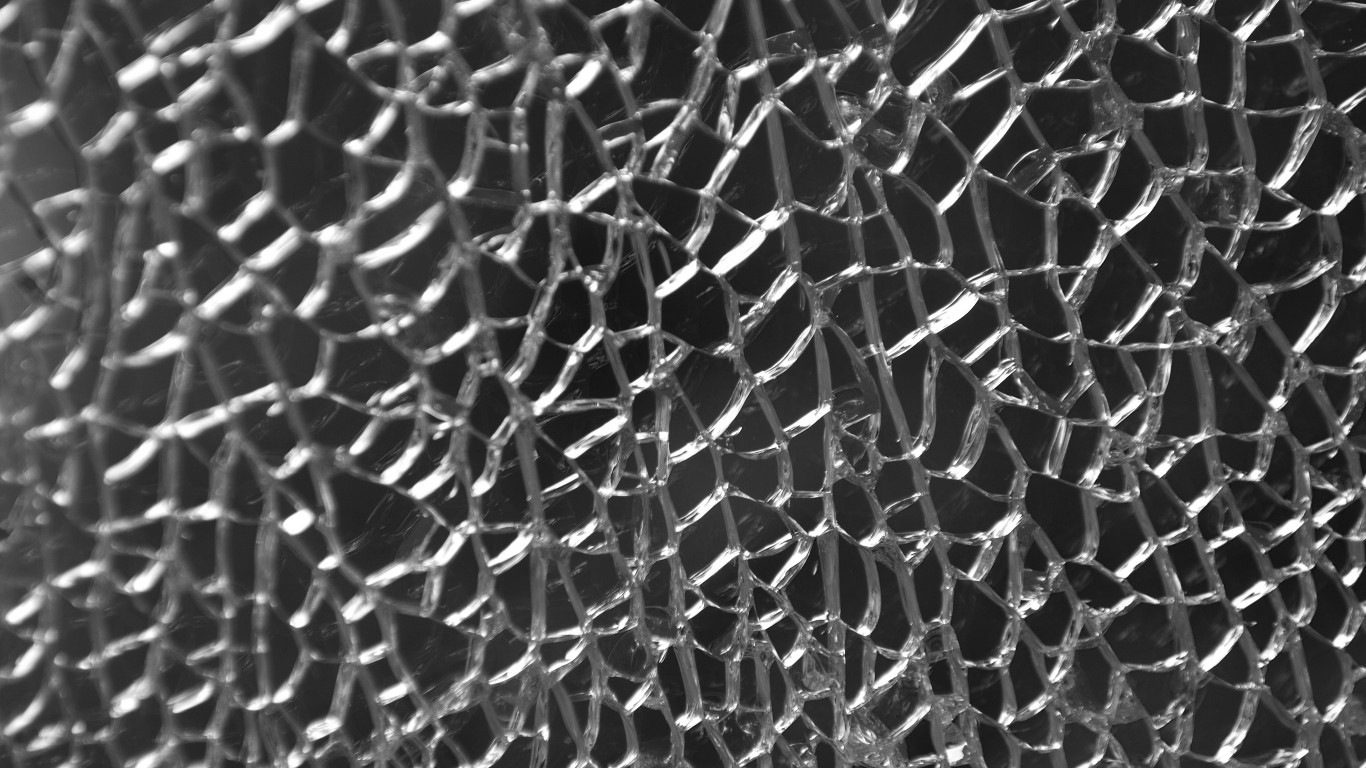

Shatterproof Glass

>Year: 1903

French artist and inventor Edouard Benedictus was tinkering in his lab when he dropped a flask that had previously contained cellulose nitrate. Although the flask broke, he noticed that the glass shards remained glued together by remnants of the cellulose compound. Benedictus recalled recent news reports of car accident victims receiving severe injuries from shattered windshields, so he began to perfect a method of laminating glass to prevent it from shattering.

Plastic

>Year: 1907

Leo Hendrik Baekeland was a Belgian-American chemist who accidentally created the recipe for the world’s first fully synthetic plastic. While attempting to create a cheaper alternative to shellac – an expensive resin harvested from lac bug secretions in South Asia – Baekeland instead created a hard, moldable polymer. Called Bakelite, his invention became indispensable for its applications in electronics, jewelry, and everyday household items like phones and clocks.

[in-text-ad-2]

Insulin

>Year: 1889

Although insulin was first extracted and isolated by University of Toronto scientists in 1921, it was an 1889 experiment that first correlated pancreatic function with diabetes. Two German physicians, Oskar Minkowski and Josef von Mering, were attempting to uncover the role of the pancreas in digestion when they surgically removed a dog’s pancreas. They later noticed flies swarming around the dog’s urine, and upon testing it discovered a high sugar content. The doctors realized that by removing the organ, they had given the dog diabetes.

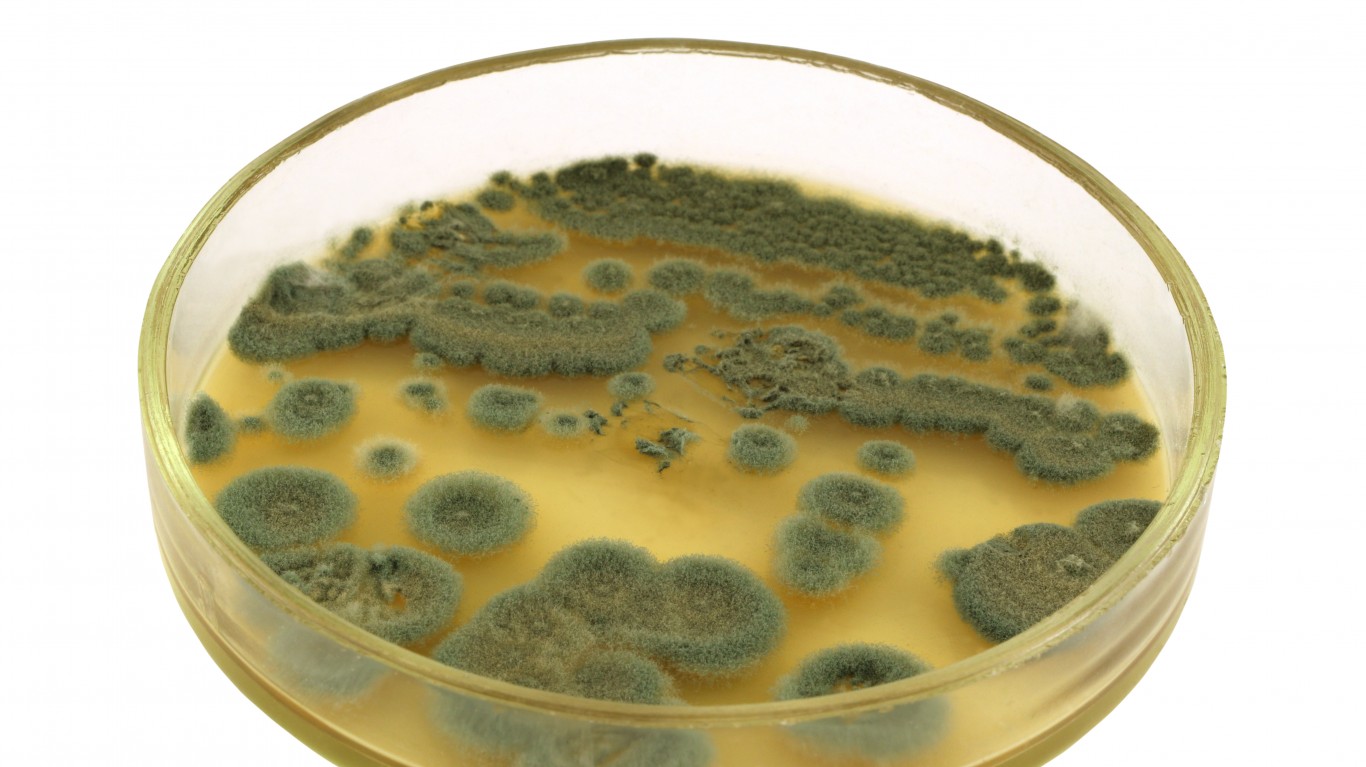

Penicillin

>Year: 1928

In September of 1928, Scottish microbiologist Alexander Fleming returned home from a vacation to find that a petri dish he’d inoculated with Staphylococcus aureus bacteria was contaminated with a fungus. Upon closer inspection, he saw that the bacteria around the fungus were dead. He later identified the fungus as belonging to the Penicillium genus and determined that it emitted an antibacterial substance that could affect the pathogens that cause scarlet fever, diphtheria, meningitis, and gonorrhea.

[in-text-ad]

LSD

>Year: 1938

While working to isolate and synthesize active constituents from plants and fungi for use in pharmaceuticals, Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman synthesized LSD. Although the initial goal of his project was to create a respiratory stimulant, Hoffman accidentally absorbed a small amount of LSD into his fingertip and experienced its powerful effects as a psychedelic drug. The substance was subsequently used to assist psychotherapy patients for a few decades before being made illegal.

Teflon

>Year: 1938

While attempting to create a new refrigerant, DuPont chemist Roy Plunkett noticed that a bottle of experimental gas had gone empty but had something solid inside it. He sawed open the bottle and found a white, waxy substance coating the glass. Plunkett subsequently patented the material, which was resistant to extreme heat and corrosive acids. It was used extensively by the Manhattan Project before being utilized as a non-stick coating for cookware.

Silly Putty

>Year: 1943

During World War II, the U.S. military was in dire need of rubber for the production of gas masks, boots, and vehicle components. General Electric engineer James Wright was attempting to create a synthetic rubber compound from silicone but instead created a bouncy, stretchy substance that his colleagues loved to play with. The substance was otherwise useless until a toy store owner named Ruth Fallgatter started selling it. It sold well and eventually her marketing consultant began packaging it in clear plastic eggs and named it Silly Putty.

[in-text-ad-2]

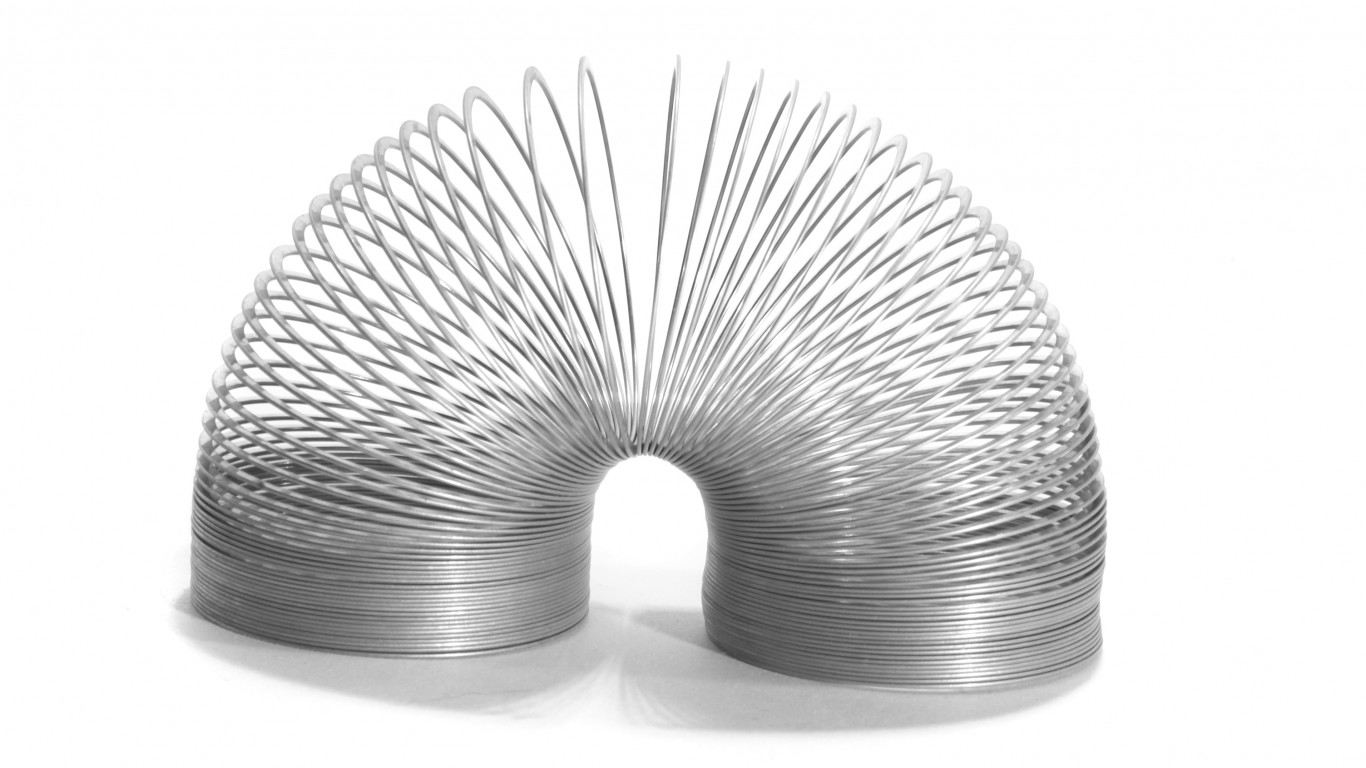

Slinky

>Year: 1943

While attempting to develop a spring mechanism that could absorb the shock of rough seas and stabilize sensitive instruments aboard ships, naval engineer Richard James accidentally knocked a spring off of a shelf. To his surprise, the spring seemed to walk itself down from a stack of books, to a tabletop, to the floor. Realizing the potential for the spring to interest children, James tweaked the steel composition until he’d developed the Slinky.

Microwave oven

>Year: 1945

During World War II, defense company Raytheon produced magnetron tubes, which were used in radar systems. While working with an active radar, Raytheon engineer Percy Spencer noticed that a chocolate bar in his pocket had rapidly melted. He began experimenting with placing the magnetron tubes in metal boxes where their waves couldn’t escape, cooking popcorn and eggs with his new contraption. Raytheon soon patented the microwave oven.

[in-text-ad]

Play-Doh

>Year: 1950s

While working for a soap company called Kutol Products, Noah McVicker invented a putty that could remove coal residue from wallpaper. Unfortunately, as in-home coal burning decreased and washable vinyl wallpapers were invented, his product became obsolete. After a tip from his nephew’s sister-in-law (a nursery school teacher), McVicker and his nephew Joe began marketing the putty as a children’s modeling clay. The two established the Rainbow Crafts Company in 1956 to sell their new Play-Doh.

Velcro

>Year: 1941

After going on a hunting trip in the Alps, Swiss engineer George de Mestral returned with burdock burrs stuck to his clothing and his dog. Intrigued by their tenacity, he looked at their hooked structure under a microscope and noticed how the hooks attached to anything with loops. After years of trial and error, De Mestral eventually patented a synthetic version of the hook and loop system as a fastener for textiles.

Super glue

>Year: 1951

While working for the Eastman Kodak company, chemist Harry Coover oversaw a team of scientists who were experimenting with materials to use in manufacturing gun sights. They accidentally created a substance so sticky that it glued together an expensive refractometer. The company eventually began marketing the substance as Eastman 910, later calling it Super Glue.

[in-text-ad-2]

Scotchgard

>Year: 1953

While attempting to develop a new kind of rubber for jet fuel lines, 3M chemists Patsy Sherman and Sam Smith were working with a substance that accidentally spilled on a lab assistant’s shoe. In trying to remove the chemical, the team realized they had discovered a waterproof, stain proof, insoluble polymer that eventually became Scotchgard.

Pacemaker

>Year: 1956

While attempting to design a piece of equipment that could record heart rhythms, engineer Wilson Greatbatch used the wrong resistor and the machine instead sent out electrical impulses at regular intervals. He presented his mechanism to surgeon William Chardack, and the two began refining and shrinking the device until it became an implantable pacemaker.

[in-text-ad]

Bubble Wrap

>Year: 1961

In 1957, engineers Alfred Fielding and Marc Chavannes were attempting to make a textured wallpaper when they sealed two shower curtains together, creating numerous air pockets in the space between. Their creation failed as a wallpaper, and instead they began marketing it as greenhouse insulation. It wasn’t until 1961 that its use as a packaging material was discovered, when IBM needed a protective material for shipping the company’s new computing unit.

The Big Bang echo

>Year: 1964

When two astronomers at Bell Labs in New Jersey were adjusting their radio telescope, they noticed some background static and thought there may have been pigeon droppings on the microwave antenna. After cleaning the instrument, however, the noise persisted. Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson had actually heard cosmic background radiation – the thermal echo of the universe’s initial expansion. Their discovery was the first substantial proof of the Big Bang theory.

Post-it notes

>Year: 1968

Attempting to develop a strong adhesive, 3M scientist Spencer Silver instead developed a reusable, low-tack, pressure sensitive adhesive that didn’t damage or leave marks on surfaces. The invention went unused for years until Silver’s colleague, Art Fry, needed a way to stick bookmarks into his hymn book at choir practice. Fry eventually developed the Post-it note as a sticky bookmark.

[in-text-ad-2]

Botox

>Year: 1987

Canadian doctor Jean Carruthers was one of the first doctors to use botulinum toxin – which can paralyze facial muscles – for medical purposes in Canada. After treating multiple eyelid spasm patients with injections that stopped their spasms, the doctor saw that the patients’ faces were also serene and free of wrinkles. Together with her husband, dermatologist Alastair Carruthers, she pioneered the concept of using botox for cosmetic purposes.

Viagra

>Year: 1992

During a Pfizer trial of a new drug intended to treat heart-related chest pain, many test subjects reported that although the drug did little to relieve their pain, it did give rise to a fortuitous side-effect. Pfizer quickly switched gears and patented Viagra in 1996 for the treatment of erectile dysfunction.

In 20 Years, I Haven’t Seen A Cash Back Card This Good

After two decades of reviewing financial products I haven’t seen anything like this. Credit card companies are at war, handing out free rewards and benefits to win the best customers.

A good cash back card can be worth thousands of dollars a year in free money, not to mention other perks like travel, insurance, and access to fancy lounges.

Our top pick today pays up to 5% cash back, a $200 bonus on top, and $0 annual fee. Click here to apply before they stop offering rewards this generous.

Flywheel Publishing has partnered with CardRatings for our coverage of credit card products. Flywheel Publishing and CardRatings may receive a commission from card issuers.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.