A report published in Science in May forecast dire futures for the many of the largest and most famous lakes on our planet, more than half of which have lost vast amounts of water over the previous three decades.

The lead author of the report was Fangfang Yao, a University of Virginia surface hydrologist and a visiting scholar at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder. Yao and his colleagues utilized satellite observations from 1992 to 2020 to get estimates of area and water levels of nearly 2,000 freshwater bodies across the globe. They found that about 53% of the world’s lakes, regardless of hemisphere, have visibly shrunk, losing a total of about 22 billion metric tons of water a year over the 28-year time span. About one-fourth of the Earth’s population lives in areas with significant lake water losses.

Desiccation of lakes has been part of the natural order of things since the planet was formed. Lake water levels fluctuate due to natural climate variations in rain and melt from snowfall. But lakes have been drying up faster than usual in recent years for many reasons – among them climate change, which accelerates evaporation; prolonged drought; excessive water use; government mismanagement; and sedimentation. (These are the countries facing the worst climate emergencies.)

The results are many: a decrease not just in water quantity but also its quality, including more toxic algal blooms; dust storms throwing toxins into the air from exposed lake beds and a surge in wildfires in newly arid areas surrounding the lakes; a decline in aquatic life, depriving migratory birds of food; and the curtailment of water-dependent activities like fishing and recreation, which may in turn affect livelihoods.

To compile a list of rapidly drying lakes, 24/7 Tempo used numerous sources, including Earth Observatory, a NASA website sharing images and discoveries about the environment; the United States Geological Survey; and various news and scientific sites. We considered water level changes and hydrological trends to identify lakes most immediately in danger of running dry.

Click here to read about 20 famous lakes that are going dry

In addition to those bodies of water that are drying up, many lakes once vital to their environments, for both human and non-human purposes – among them Lake Poopó in Bolivia and Lake Sawa in Iraq – have already completely disappeared, drying entirely into dust bowls or salt flats, with sometimes devastating effects on their surroundings. In fact, another dry lake, Lake Owens in California was once the largest source of toxic dust in America, until mitigation efforts by the Department of Water & Power significantly reduced emissions. (These are the largest lakes in America.)

Lake Mead, Nevada & Arizona

Although the water level of Lake Mead – a reservoir on the Colorado River east of Las Vegas, formed by Hoover Dam – reached 1,045.91 feet above sea level in early April, almost three feet higher than the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation had predicted a month earlier, it is still an endangered body of water. Between the 1970s and 1990s, the lake neared full capacity on numerous occasions, attaining a record high of 1,225 feet in 1983. A year ago, in contrast, it was filled to just 27% of capacity. Lake Mead is shrinking because of prolonged drought as well as increased water demand from the Southwestern states and California.

[in-text-ad]

Caspian Sea, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Azerbaijan, & Russia

The Caspian – the world’s largest inland water body as measured by surface area – is often considered a lake, though it might better be described as an inland sea. Radar altimetry data collected by satellites and compiled by NASA’s Global Water Monitor shows that the Caspian’s water level has been dropping since the mid-1990s. (The Iranian Space Agency tracked a decline of more than 10 inches between March 2022 and March 2023 alone.) Scientists using models to estimate future water loss have projected that by 2100, water levels could drop by as much as 98 feet more. The diversion of water from rivers that feed the Caspian has been a factor in the decline.

Aral Sea, Kazakhstan & Uzbekistan

The Aral Sea, formed by the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya rivers, was once the fourth largest lake in the world. In the 1960s, the Soviet Union began a water diversion project that drained the Aral by more than 90%. As it dried up, fisheries and the communities that depended on them collapsed and the Aral became saltier, and polluted with fertilizer and pesticides. Because of human intervention, the decline of the Aral Sea has been called one of the planet’s worst environmental disasters.

Salton Sea, California

The Salton Sea was created in the early 20th century by accident – an irrigation canal off the Colorado River burst and flooded the Salton Basin. It became a popular residential and vacation spot. But over the last few decades, climate change and drought have led to receding waters – over the last 25 years, the Sea has lost a third of its volume – and it has become California’s most polluted inland lake. Its future depends on the levels of the Colorado River, which has itself been lowered by drought.

[in-text-ad-2]

Great Salt Lake, Utah

The Great Salt Lake is one of the largest saline lakes in the Western Hemisphere, but also one of the most endangered. A report published in early January by scientists at Brigham Young University revealed that the lake was at only 37% of its former volume, and predicted that it would go completely dry within five years barring substantial cuts in water consumption. The decline in water has been exacerbated by persistent drought – and though runoff from a record snowpack in the Uinta Mountains brought water levels up as much as five feet this spring, some 50% of the lakebed is still dry, and authorities describe the inflow as “a drop in the bucket.”

Lake Mar Chiquita, Argentina

Mar Chiquita is an endorheic, or closed-basin, shallow salt lake in central Argentina. When its water level is high, the lake covers as much as 2,300 square miles. When low, it shrinks to 770 square miles, exposing large tracts of salt and mud flats. The lake, once a tourist spot, is slowly losing water volume because of increased evaporation and the elevation of its bottom, and scientists believe it will eventually turn into a salt flat.

[in-text-ad]

Lake Powell, Utah & Arizona

In February, water levels in Lake Powell, formed by the Colorado River flowing into Glen Canyon, dropped to 3,522.16 feet above sea level, below the prior record set in April 2022. The nation’s second-largest reservoir, on the border of Utah and Arizona, it suffers from the effects of climate change, including sustained drought conditions, and from increased demand for its water, which is used by seven states.

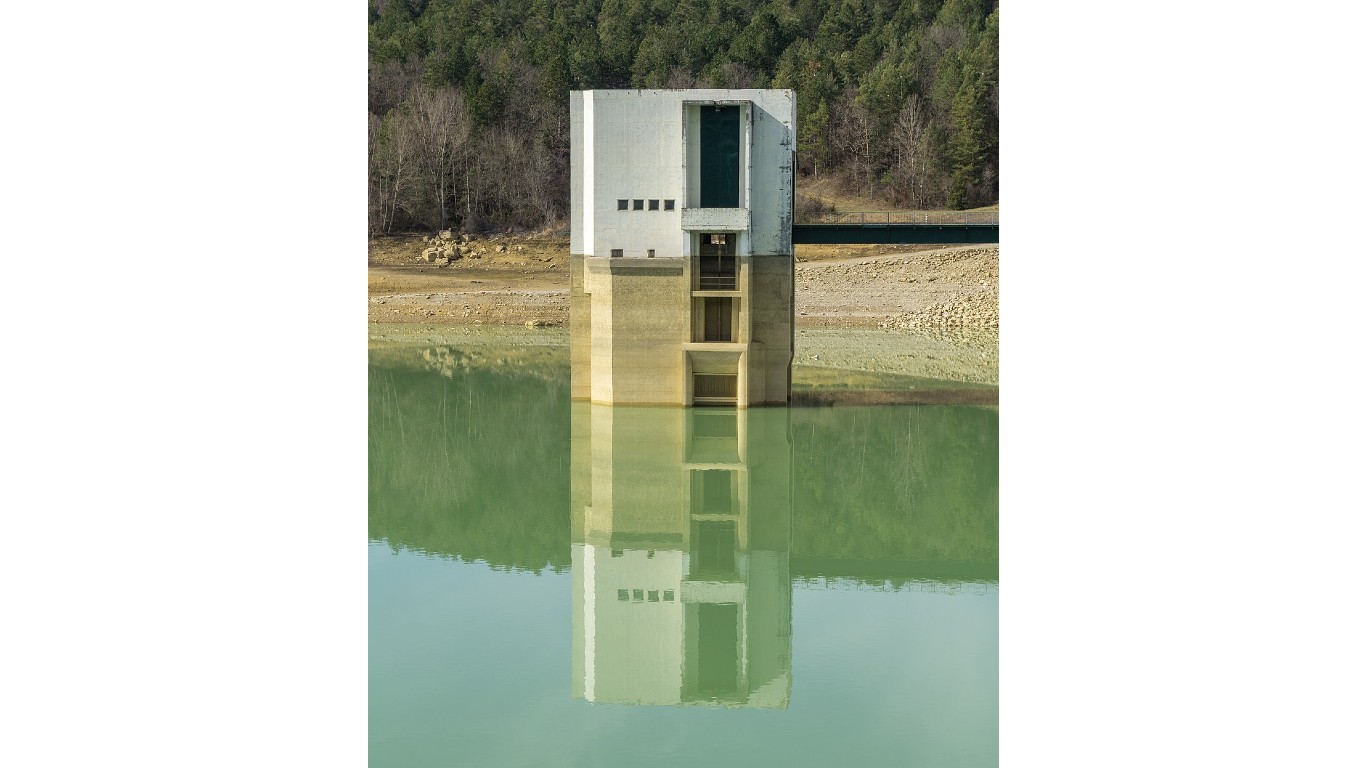

Lake Montbel, France

Lake Montbel, or Lac de Montbel, at the foot of the Pyrenees Mountains in southern France, was at 28% capacity as of March. The lake began receding in the summer of 2022 and the region’s driest winter in more than six decades has exacerbated the dire situation. France had more than 30 straight days with no measurable rainfall between January and February. That’s the longest period since record-keeping began in 1959. In addition, snowfall has been very low, meaning a decrease in snowmelt that replenishes the rivers that feed the lake.

Lake Tahoe, Nevada & California

Lake Tahoe, on the border of Nevada and California, is one of the highest lakes in the world, at 6,225 feet above sea level. The largest alpine lake in North America, Tahoe has suffered in recent years because of drought, wildfires, toxic runoff, and litter. So far, the water level has receded by only a few feet, with last fall marking its lowest point in recent years, but the melting snowpack this year has helped refill it almost to its maximum capacity. Nonetheless, drought will be an ongoing problem at least until the end of this decade – and whenever the lake falls below its natural rim of 6,223 feet, as it did in 2012, it stops flowing into the Truckee River, of which it is an important source.

[in-text-ad-2]

Lake Chad, Nigeria/Niger/Chad/Cameroon

Once the size of the Caspian Sea, Lake Chad has shrunk by around 90% since the 1960s. Water is receding due to reduction in precipitation due to climate change, development of modern irrigation systems for agriculture, and the increasing demand for freshwater as local populations grow. The four nations that share its shoreline, along with Libya and the Central African Republic, have joined together to form the Lake Chad Basin Commission, one of whose projects is the construction of a 1,490-mile canal to transport water to the lake from the Congo River.

Penuelas Lake, Chile

The water of Penuelas Lake could once fill 38,000 Olympic swimming pools; now it has almost entirely dried up. This has led to water shortages in Valparaiso and other Chilean towns in the region. Experts blame the drought that is starving the lake – the longest-lasting in at least 400 years – on greenhouse gasses that are thinning the ozone layer over Antarctica. This reduces the number of storms along the coast of Chile. Elevated temperatures mean snow in the Andes, key for creating meltwater, melts faster, or turns to vapor before it reaches the lake.

[in-text-ad]

Walker Lake, Nevada

Walker Lake is a natural lake fed by the Walker River, though it has no outlet. Since the middle 1800s, water from the Walker River and its tributaries has been diverted for agriculture, causing the level of the lake to plummet by 180 feet since 1882, when such measurements began. The Walker Basin Conservancy, a nonprofit organization trying to restore the lake to healthy levels, calls the lake’s decline “an ecological tragedy more than a century in the making.” Increasing salinity in the lake is why wildlife such as loons no longer visit it.

Lake Victoria, Kenya/Tanzania/Uganda

A study published by Earth and Planetary Science Letters in 2019 said Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa, could dry up more quickly than researchers previously realized, and that the White Nile tributary – the only outlet for Lake Victoria – could vanish within a decade. The water level of Lake Victoria has fallen almost five feet since 1998, due to reduced rainfall and the effects of evaporation, exposing a narrow strip of land along the shore. The study determined that the recent drop in the water level has created additional breeding grounds for malaria vectors.

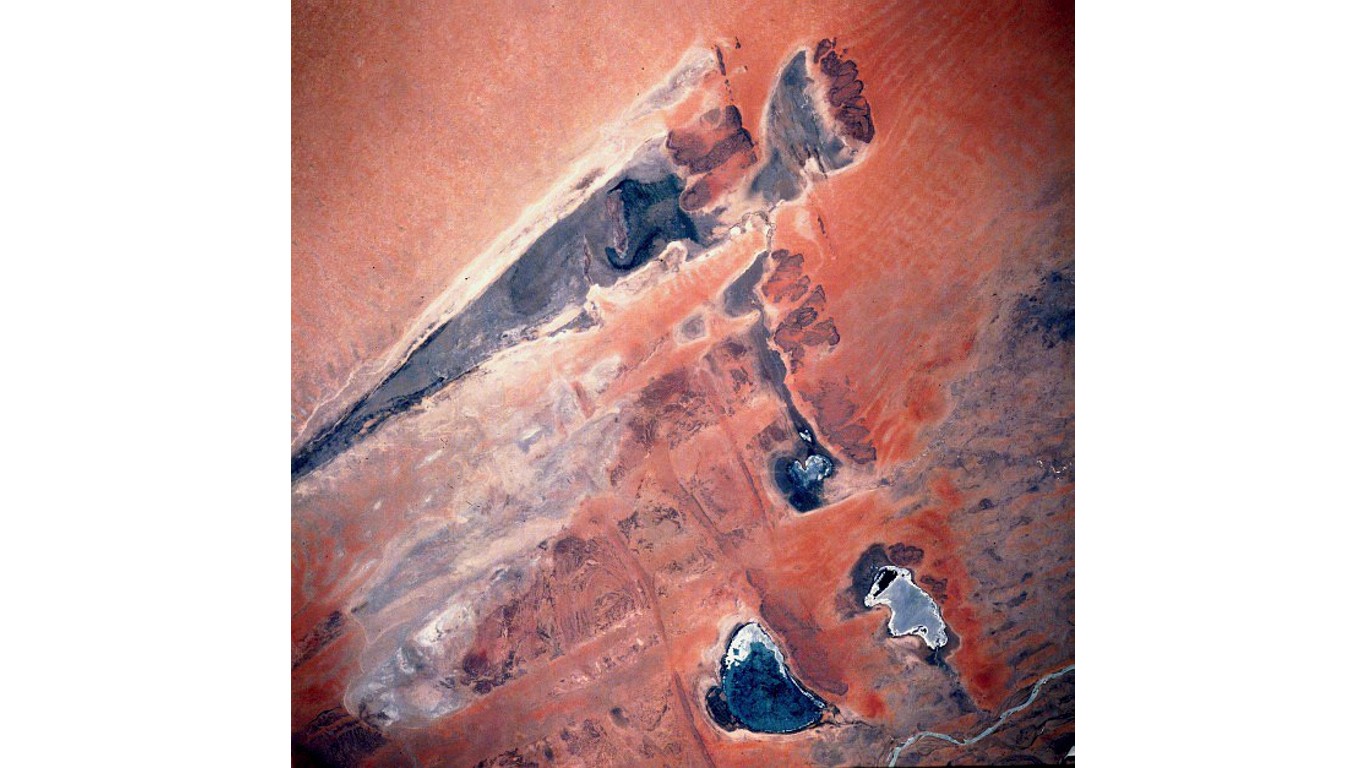

Lake Faguibine, Mali

Lake Faguibine, lying at the end of a series of basins replenished by the Niger River when it floods, has experienced widely fluctuating water levels for decades. At its fullest, the lake was among the largest in West Africa; in 1974, it covered about 230 square miles. Since the Sahel drought of the 1970s and ’80s, though the lake has been dry most of the time, only occasionally filling partially with water.

[in-text-ad-2]

Lake Titicaca, Peru/Bolivia

Lake Titicaca, a freshwater lake between Peru and Bolivia, is perched atop the Andean Altiplano at over 12,000 feet in elevation. It is the largest lake in South America, with a surface area of over 3,200 square miles. Its water level has decreased since 2000 due to shortened rainy seasons and shrinking glaciers, reducing snowmelt water flows into the lake. It is also vulnerable to the evaporative effects of solar radiation, and is currently approaching all-time lows.

Lake Puzhal, India

Lake Puzhal, a rain-fed reservoir near Chennai, India’s sixth largest city, is losing water at a rapid rate. The monsoon rains that feed the lake have been unreliable since 2017. A satellite image showed a dramatic drop in water from 2018 to 2019. This has led to tension in Chennai, a city of 10 million people. Tarun Gopalakrishnan, a climate change expert at the New Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment, said the crisis in Chennai is the result of “a toxic mix of bad governance and climate change.”

[in-text-ad]

Poyang Lake, China

Poyang Lake is the largest freshwater lake in China. Drought, sand quarrying, and the impact of the massive Three Gorges Dam are responsible for the shrinking of the lake’s surface area. In 2022, a heat wave and drought across much of the Yangtze River Basin pushed water levels to their lowest in decades. This February, the water level dropped to about 23 feet, one of the lowest levels ever recorded. The impact of the diminished lake has disrupted irrigation, shipping, and drinking water systems.

Lake Chapala, Mexico

The level of Lake Chapala, Mexico’s largest freshwater lake, has dropped to record lows since 1979, to the point that it is now only half full, with an average depth of about nine feet. A surge in sedimentation from the Lerma River, Lake Chapala’s major source, has raised water temperature, increasing evaporation. The depth of the lake – which plays a key role in the economy and ecosystem of the region – has also been decreasing because of greater water for irrigation and industrial needs (about 20 million people live in the vicinity).

Lake Abert, Oregon

Lake Abert, a shallow, salty lake in southern Oregon, has long been a stopover for birds migrating from Alaska and Canada to California, Mexico, and South America who fed on its alkali flies and brine shrimp. But the lake nearly dried up four times since 2014 because of water withdrawals and dry weather. That caused the salinity level in the already saline lake to spike to levels that were too high even for the flies and shrimp.

[in-text-ad-2]

Mono Lake, California

Beginning in 1941, water from the streams emptying into the lake was diverted by the city of Los Angeles. Over the next 40 years, Mono Lake’s level dropped by 45 vertical feet, it lost half its volume, and it doubled in salinity. This impact has threatened the survival of the California gull population and damaged air quality with toxic dust storms. As of Aug. 1, Mono Lake was 9.1 feet below the management level.

Get Ready To Retire (Sponsored)

Start by taking a quick retirement quiz from SmartAsset that will match you with up to 3 financial advisors that serve your area and beyond in 5 minutes, or less.

Each advisor has been vetted by SmartAsset and is held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests.

Here’s how it works:

1. Answer SmartAsset advisor match quiz

2. Review your pre-screened matches at your leisure. Check out the advisors’ profiles.

3. Speak with advisors at no cost to you. Have an introductory call on the phone or introduction in person and choose whom to work with in the future

Get started right here.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.