When the Earth’s atmosphere becomes saturated with smoke and soot generated by nuclear bomb-induced firestorms, resulting in a significant reduction or absence of sunlight reaching the planet’s surface, this period is referred to as a nuclear winter. (These are countries that control the world’s nuclear weapons.)

To describe what would happen in a nuclear winter, 24/7 Wall St. referenced a research article published by Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, Nuclear Winter Responses to Nuclear War Between the United States and Russia in the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model Version 4 and the Goddard Institute for Space Studies ModelE, and an article in the Smithsonian magazine.

The consequences of nuclear war on the climate can vary, depending on how large the conflict is. To date, the concept of a nuclear winter remains a theory, subject to both proponents and critics. (These are 18 of the deadliest weapons of all time.)

This notion first gained prominence in the 1970s, propelled by a group of scientists that included the renowned astronomer Carl Sagan. Their focus lay on dissecting the environmental aftermath of a nuclear exchange. In 1983, Sagan articulated his views in an article for Parade magazine, predicting an immediate death toll of 1 billion from a major nuclear conflict, with potentially graver long-term ramifications.

By leveraging computer models crafted by meteorologists and research conducted by Sagan and his former students, scientists in 1980 deduced that the onset of a nuclear winter wouldn’t necessitate a comprehensive nuclear engagement. They found that global average temperatures could plummet by up to 25 degrees Celsius after a nuclear war. This chilling scenario would usher in an extended epoch of darkness, famine, and worldwide toxic gases.

Sagan’s stance in the nuclear-winter discourse faced opposition from physicist Edward Teller, a key figure in the development of the hydrogen bomb. Teller fervently championed the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), an envisioned satellite system for safeguarding against nuclear missiles. Teller and other defense proponents believed that advocates of nuclear winter could erode support for SDI.

While the notion of nuclear winter is haunting, a parallel from history exists. In 1980, paleontologist Luis Alvarez and his physicist father Walter proposed evidence that an asteroid impact terminated the Cretaceous Period 66 million years ago. Their hypothesis suggested that the resultant injection of dust and debris into the atmosphere darkened Earth for a prolonged duration, leading to the extinction of non-bird dinosaurs. This hypothesis underscores the potential for a localized catastrophe to wield far-reaching, lasting impacts on the entire planet.

Click here to see what would happen in a nuclear winter

23. Urban fires

Urban fires from the first nuclear strike would cause sooty smoke, or black carbon, arising from a city’s ruins. Though smaller in magnitude, when black carbon was injected into the atmosphere 66 million years ago – when an asteroid impact caused much of the Earth’s surface to burn – it resulted in a mass extinction event.

[in-text-ad]

22. Forest wildfires

Wildfires ignited from a firestorm after a nuclear weapons exchange would contribute to a nuclear winter.

21. Smoke from fallout

Smoke from fallout would block out sunlight for years, causing below-freezing temperatures.

20. Soot in stratosphere

Black carbon would absorb radiation and heat up from sunlight. As a result, the surrounding air would become buoyant, lifting soot into the stratosphere.

[in-text-ad-2]

19. Winds carry soot

The buoyant aerosols would reach the higher levels of the stratosphere, encountering winds that would distribute the smoke over the Earth.

18. Black carbon and precipitation

If black carbon stays in the troposphere it can trigger precipitation. When it is in the stratosphere, black carbon stays there for years, leading to global climate response. Without precipitation as a removal mechanism, aerosols can remain in the stratosphere for months to years depending on particle size.

[in-text-ad]

17. Northern Hemisphere soot

After a nuclear exchange, almost the entire Northern Hemisphere would be engulfed in stratospheric soot within the first week.

16. Southern Hemisphere soot

Two weeks after a nuclear conflict, soot would have traveled to the Southern Hemisphere.

15. Reduced sunlight

Sunlight would be reduced by as much as 90% in some areas after a nuclear war.

[in-text-ad-2]

14. Acid rain

According to some studies, up to 25% of smoky soot would fall back to Earth in a heavy black and acidic rain.

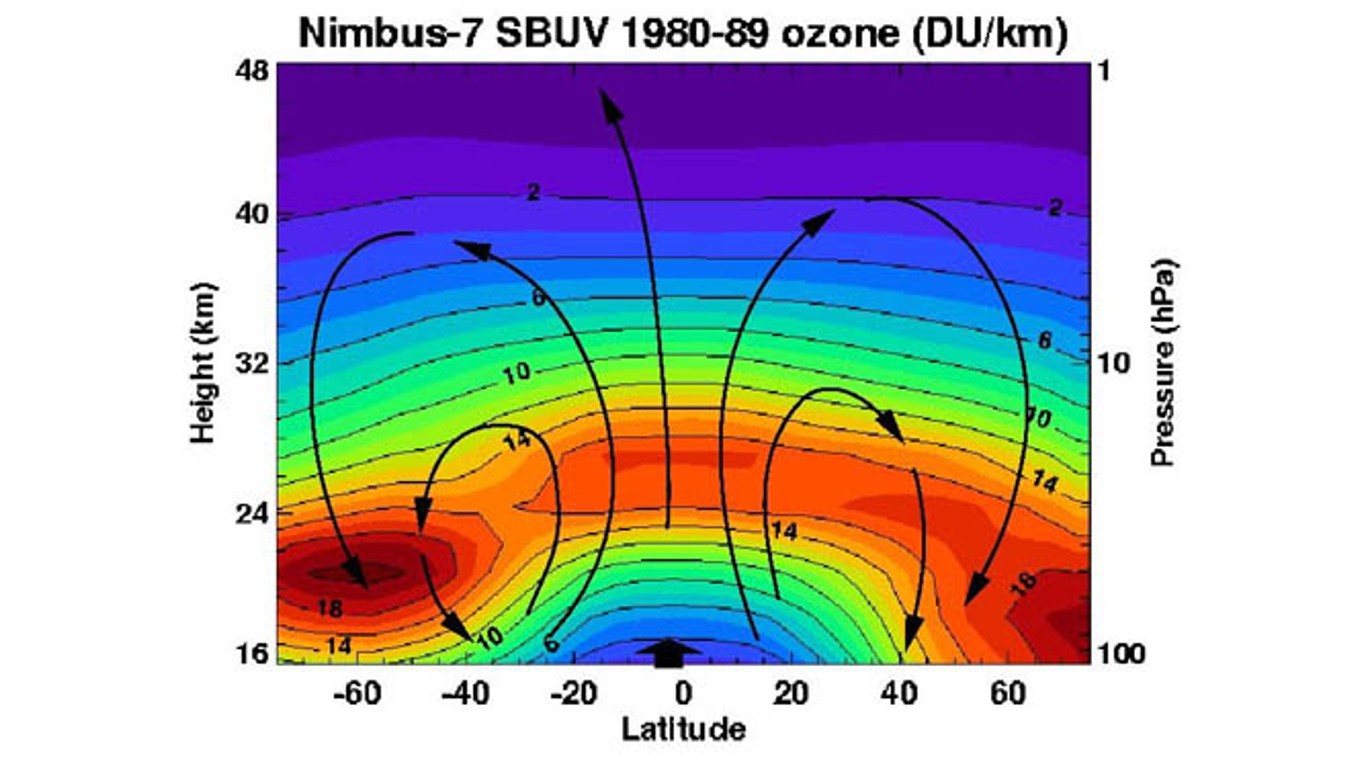

13. Slowing circulation in stratosphere

Once in the stratosphere, soot can remain for a longer time by slowing in the Brewer-Dobson circulation — which is characterized by tropospheric air rising into the stratosphere in the Tropics, moving poleward before descending in the middle and high latitudes. This is because of surface cooling and reduced convection.

[in-text-ad]

12. Reduction in surface temperature

Models show a significant reduction in global mean surface temperature. Sulfate aerosols generated from gasses injected into the stratosphere by volcanic eruptions would cause global cooling because of the reflection of incoming solar radiation into space. This has been observed numerous times in previous volcanic eruptions. Surface temperatures would be cooler than the last ice age 18,000 years ago.

11. Diminished surface light

Surface light levels would remain under 40% of normal for three years. Low-light levels in the summer would be problematic for organisms that depend on photosynthesis to survive.

10. Stratospheric ozone losses

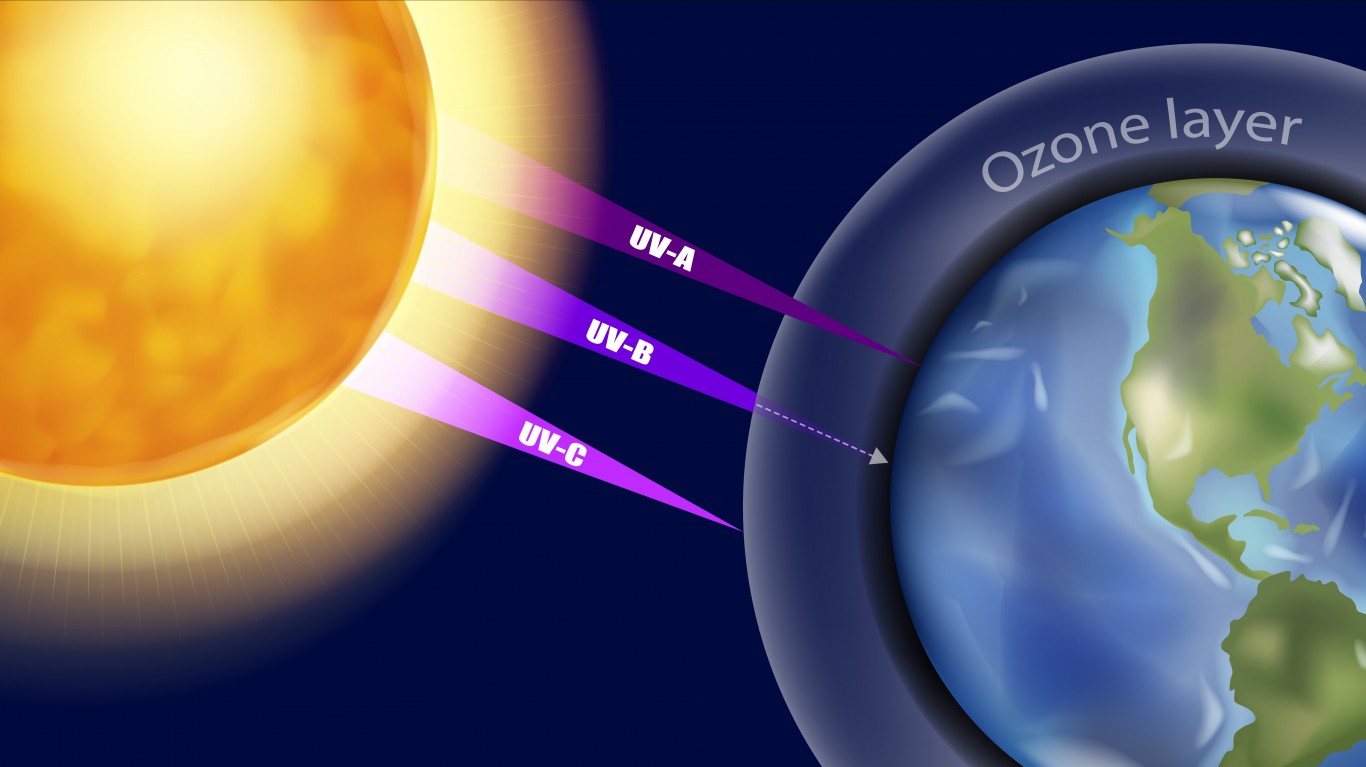

Absorption of solar radiation by soot would boost extreme stratospheric temperature changes. The increases in temperature of this magnitude would result in large losses of stratospheric ozone, allowing more unfiltered ultraviolet radiation to reach the surface.

[in-text-ad-2]

9. Water vapor

The photolysis of water vapor – the breakdown of water molecules into protons, electrons, and oxygen in the presence of light – would exacerbate ozone destruction, which would already be at higher levels because of stratospheric heating.

8. Precipitation declines

Global precipitation averages would drop by about 58% after soot injection into the stratosphere. The global hydrologic cycle would become much less active, with a reduction in summer monsoon precipitation.

[in-text-ad]

7. Rainfall pattern changes

There would be changes in rainfall patterns during a nuclear winter. The monsoon rains would weaken, and more rainfall would occur over desert areas. The weakening of the summer monsoon has been observed following volcanic eruptions.

6. Growing season reduced

Following a nuclear war, during a nuclear winter, the growing season would be 90% reduced across many parts of the midlatitudes.

5. Crop failures

Not only would the growing season be reduced, but agricultural modelings of a regional nuclear war show an increased likelihood of crop failures.

[in-text-ad-2]

4. Famine

Global famine would follow widespread crop failures.

3. Photosynthesis disrupted

Solar radiation, important not only for surface temperatures but also for photosynthesis, would drop by 60% to 70% in the first few years of a nuclear winter.

[in-text-ad]

2. Nuclear winter

The varying scenarios for the theoretical nuclear winter depend on the severity of nuclear weapons exchange. Still, dark skies, widespread drought, fallout, and global temperature drops to those last seen in the previous ice age would occur in the Northern Hemisphere.

1. Mass extinction

In the worst-case scenario of a nuclear winter, a mass extinction event would take place.

100 Million Americans Are Missing This Crucial Retirement Tool

The thought of burdening your family with a financial disaster is most Americans’ nightmare. However, recent studies show that over 100 million Americans still don’t have proper life insurance in the event they pass away.

Life insurance can bring peace of mind – ensuring your loved ones are safeguarded against unforeseen expenses and debts. With premiums often lower than expected and a variety of plans tailored to different life stages and health conditions, securing a policy is more accessible than ever.

A quick, no-obligation quote can provide valuable insight into what’s available and what might best suit your family’s needs. Life insurance is a simple step you can take today to help secure peace of mind for your loved ones tomorrow.

Click here to learn how to get a quote in just a few minutes.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.