Fifty years after President Richard Nixon’s historic flight to China that heralded closer and warmer ties between the U.S. and the communist country, relations between the world’s top economies have chilled considerably.

Tensions remain high since former U.S. President Donald Trump escalated confrontation with the People’s Republic of China over long-simmering concerns about the country’s authoritative, state-controlled capitalism, rising militarization, and approach to human rights. The Americans had hoped that opening trade relations would instill a more liberal Chinese government system but now seem fed up with China’s state capitalist system.

For their part, the ruling Chinese Communist Party under President Xi Jinping accuses the U.S. of attempting to suppress the country’s development as China attempts to shift away from its heavy reliance on factory work to an economy focused on domestic consumption. Chinese officials also view the U.S. as a superpower in decline, wreaked domestically with ongoing racial injustices, growing income inequalities, cultural polarizations, and political gridlock. (Also see, comparing America’s 20 richest cities to China’s.)

With the many issues between the two countries, it is worth looking back at the history of U.S.-China relations, particularly the decades leading up to the communist takeover of the country in 1949.

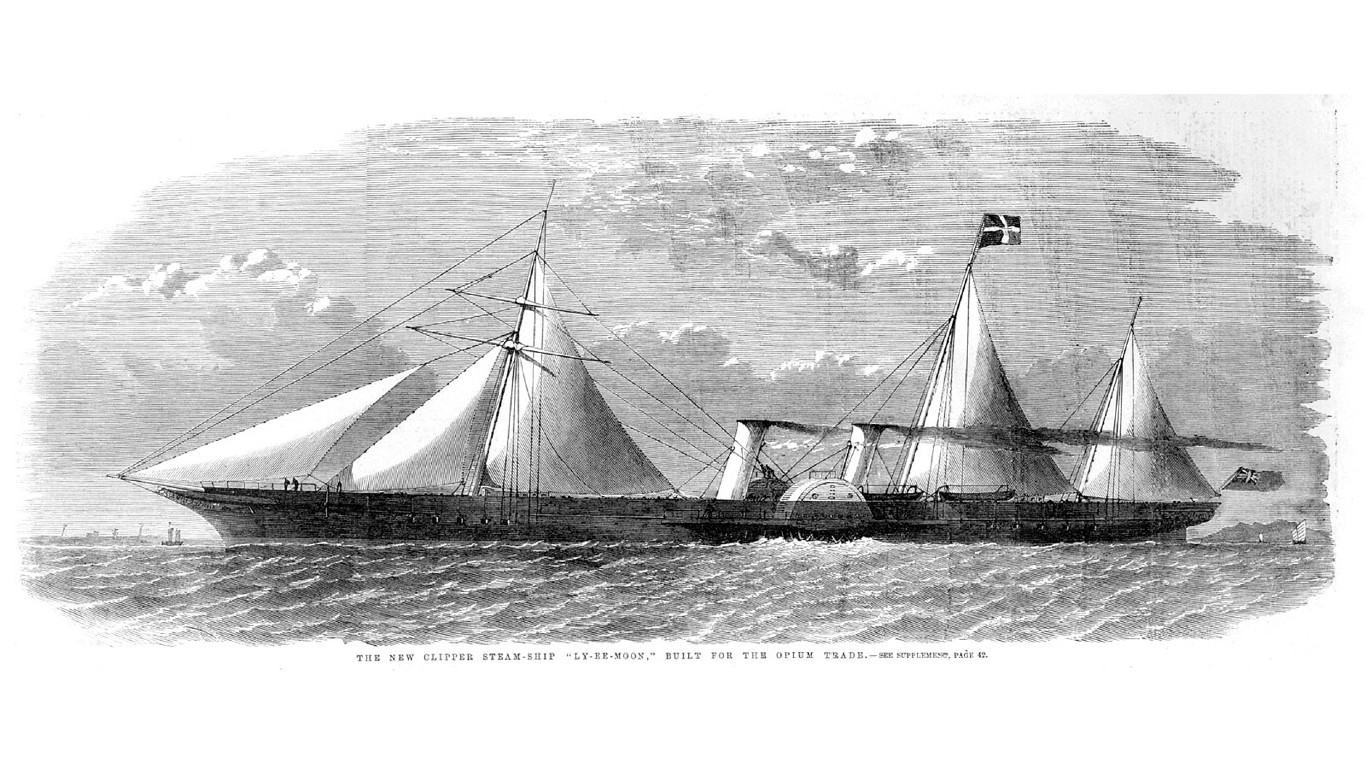

These actions date back to 1843, when the U.S. first deployed forces on Chinese soil in the wake of Britain’s victory in the First Opium War — actions that underscore just how turbulent China’s history was prior to the emergence of communism under Mao Zedong and his “Great Leap Forward” that led to the death of tens of millions of Chinese during the Cold War.

To identify the 25 times the United States has sent armed forces to China, 24/7 Wall St. reviewed “Instances of Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad, 1798-2023,” a report updated June 7, 2023 by the Congressional Research Service.

U.S. military interventions in China can be divided into three categories: the latter half of the 19th century as Western powers (namely Britain and the United States) pried open trade concessions through violence and coercion; the tumultuous period in the early years of the 20th century that led to the end of China’s imperial dynasties and eruption of civil war; and the years leading up to and through World War II and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. (See China’s 8 biggest weapons manufacturers and what they build.)

This period includes British traders flooding China with opium and two wars the Chinese fought against Japanese occupiers — events that fostered anti-foreigner sentiment among the Chinese population that required the U.S. to routinely deploy forces to protect its citizens and trade interests.

Here is every time the U.S. sent military forces to China.

1843

The USS St Louis, the flagship of the U.S. East Indies Squadron, landed Marines at a southern Chinese trading post in Canton (today known as Guangzhou) amid a clash between Americans and Chinese. The incident occurred months after Britain’s victory in the First Opium War that ended the Qing Dynasty’s “Canton system” that restricted all trade with foreign entities to a single port of entry. In 1844, The U.S. signed its first treaty with China in order to obtain similar trade concessions Britain had won with its 1842 treaty.

[in-text-ad]

1854

From 1850 to 1864, China was divided by the Taiping Rebellion that challenged the authority of the country’s imperial Qing government, which barely survived the rebellion that originated in the country’s southeast. The civil strife compelled the Americans and English to deploy forces to protect their interests in and near Shanghai from April to June 1854.

1855

A year before the start of the Second Opium War (1856-1860) waged between Britain and France against China’s Qing dynasty over trading privileges, the U.S. deployed forces to China twice: once to protect American interests in Shanghai in May 1855 and again in August of that year to fight pirates near Hong Kong.

1856

As the Second Opium War erupted, the U.S. deployed forces to protect American interests in the southern Chinese city of Canton (today known as Guangzhou) after an unarmed ship displaying the U.S. flag was attacked.

[in-text-ad-2]

1859

A year before the Beijing Agreement ended the Second Opium War with deep trading concessions to Western powers, including British control of the local opium trade it started as a smuggling operation in the 1810s, the U.S. deployed a naval force from July to August to protect American interest in Shanghai.

1866

A year after the U.S. Civil War ended, American forces were sent in the summer of 1866 to punish an assault on the U.S. consul at the northern coastal Chinese city of Newchwang, known today as Yingkou. Two years later, China sent its first diplomatic mission abroad — to the U.S. and Europe — to renegotiate treaties.

[in-text-ad]

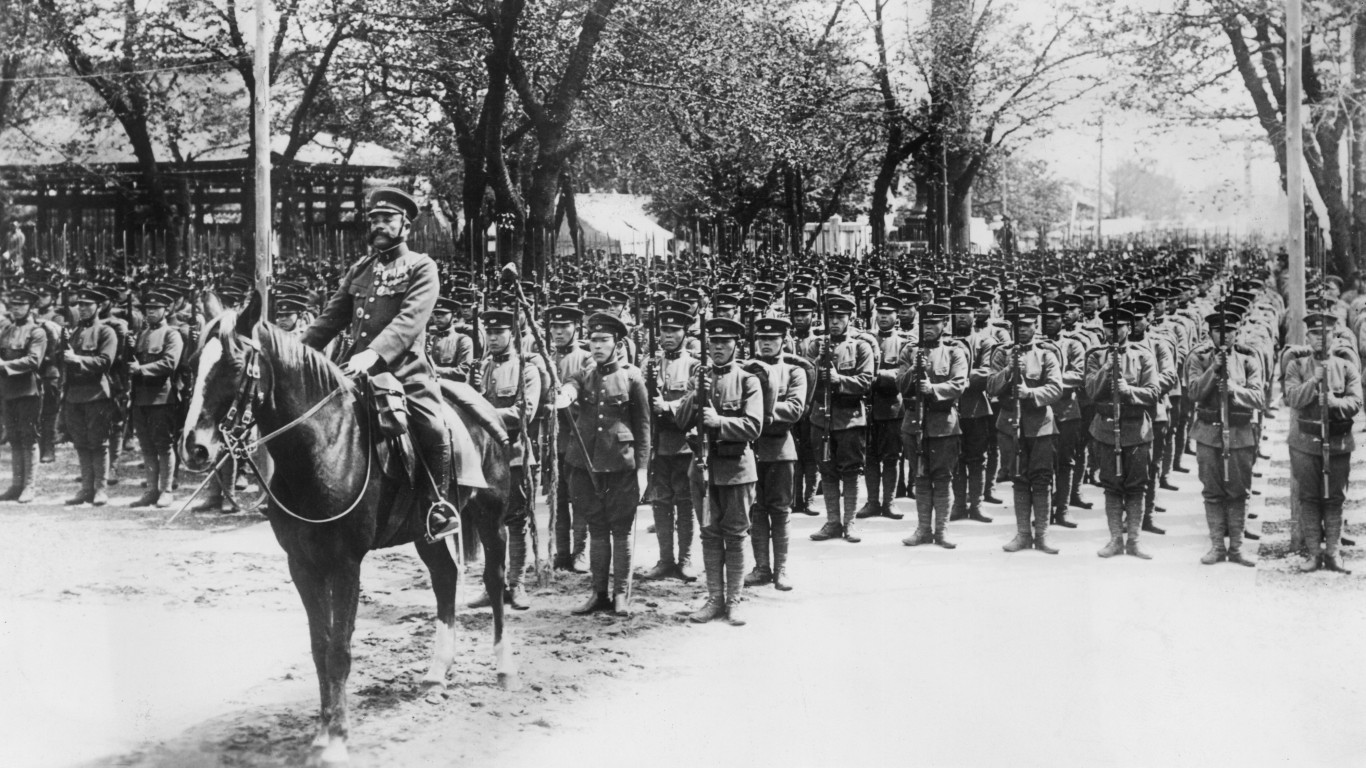

1894-1895

The First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 over influence in Korea led to a stunning victory for Japan, which took control of Taiwan and asserted the right to build factories in China. During the war, U.S. Marines from the USS Monocacy gunboat provided honor guard for a Chinese viceroy during a visit to the U.S. consulate in Tientsin (not known as Tianjin). Later in the war, a U.S. naval vessel was used in the northern port city of Newchwang (Yingkou) to protect American nationals.

1898-1899

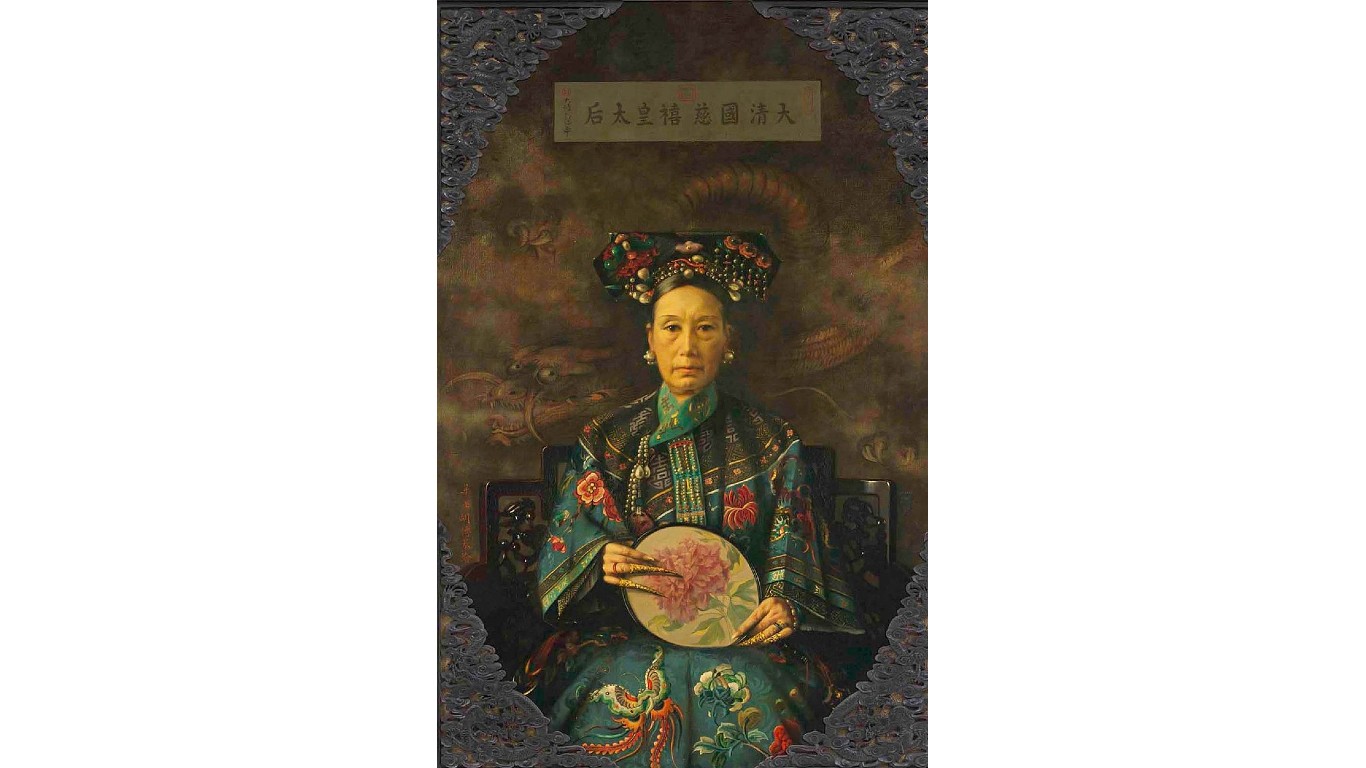

In the last years of the 19th century, reformist literati strived to institute reforms to China’s government and educational system. While imperialist conservatives, including a power struggle between the Empress Dowager Ci Xi, opposed the reforms, her nephew and adopted son, the Guangxu Emperor, supported them. During these tense months, U.S. forces provided guard to the U.S. legation at Peking (Beijing) and the U.S. consulate in Tientsin (Tianjin).

1900

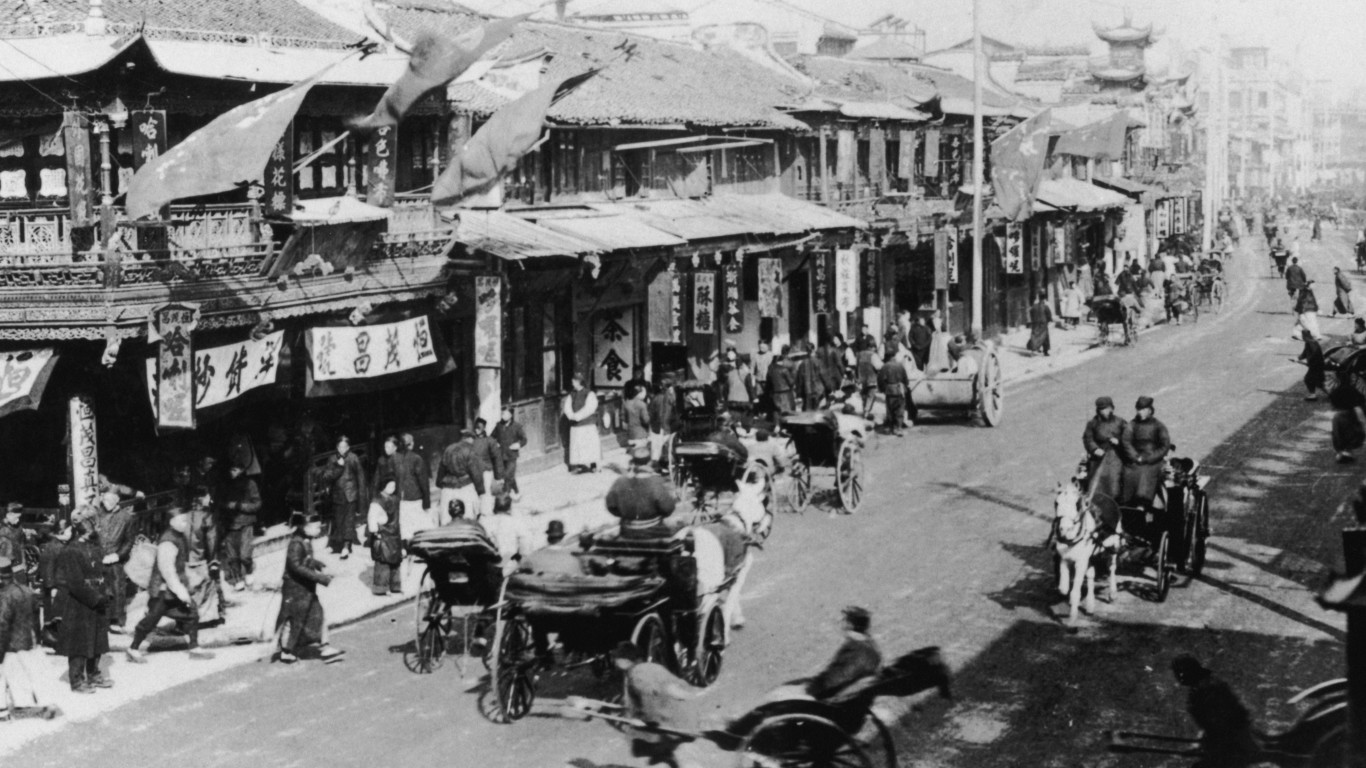

China’s Boxer Uprising (1900-1901) was marked by a rise in rural unrest, mystical cults centered around martial arts, and anti-foreign sentiment that violently targeted expatriates and Chinese Christian converts. From May to September 1900, American troops participated in operations to protect foreigners, patricianly those living in Peking (Beijing). The rebellion ended with a punishing settlement in which China’s ruling Qing government was forced to pay a penalty that essentially bankrupted the government.

[in-text-ad-2]

1911

China’s last dynasty, Qing, fell in 1911 amid a nationalist uprising that had been simmering for years. Unrest included anti-American boycotts as a result of the crackdown in the U.S. against Chinese immigrants and the failure to sign an immigration treaty. The U.S. crackdown led to mass deportations and the ghettoization of Chinese-Americans, creating Chinatowns across the country. As the Qing dynasty collapsed, the U.S. sent numerous landing forces to guard American property and to protect cable stations.

1912

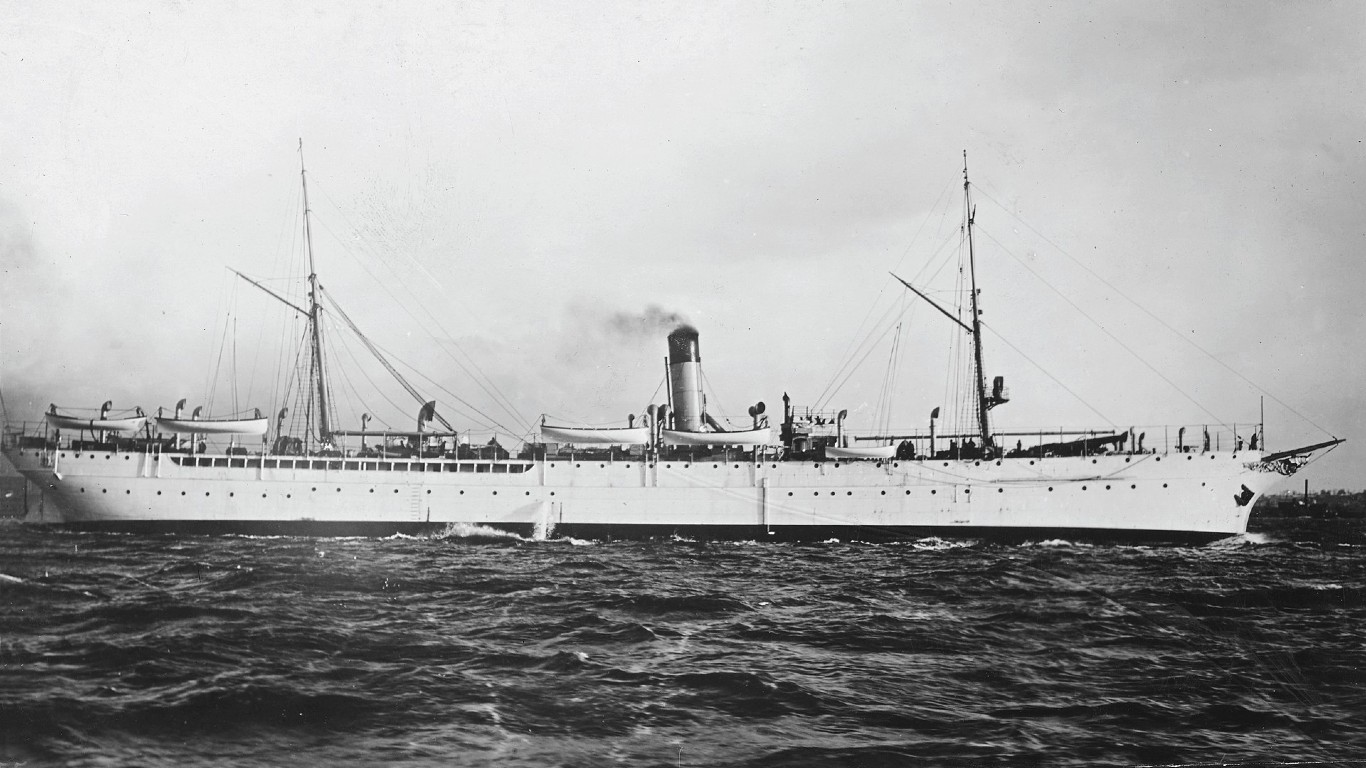

China’s revolutionary fervor continued with the creation of the Republic of China in 1912 into the country’s civil war that erupted in 1927. This unrest included the Kuomintang rebellion in 1912 that targeted outsiders. During this tumultuous period, the U.S. deployed troops numerous times to protect U.S. interests. In August 1912, U.S. Marines from the USS Rainbow, the flagship of the U.S. Philippine Squadron, were deployed twice, once to Camp Nicholson and a second time to Kentucky Island, near Shanghai.

[in-text-ad]

1912-1941

U.S. military deployments to protect American interests in China occurred routinely until World War II. The U.S. maintained a guard at Peking (Beijing) and along important nearby sea routes up to the eruption of the war, actions based on treaties signed between the two countries in the latter half of the 19th century. By the time China’s civil war erupted in 1927, the U.S. had 5,670 troops on Chinese soil and 44 naval vessels in Chinese waters.

1916

During World War I, Japan seized German territories in eastern coastal Shandong Province, and in 1915, it issued demands to the Chinese government to expand Japanese trade and territorial privileges, demands opposed by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. A year after Japan’s efforts to compromise Chinese sovereignty, American forces landed in Nanking (Nanjing) to quell a riot on U.S. property.

1917

In 1916, Chinese military and government official Yuan Shikai attempted to keep China together by declaring himself emperor, but he died quickly after his proclamation. China then collapsed into its so-called Warlord Period of regional fiefdoms barely united under a national regime in Peking (Beijing). The U.S. maintained relations with this weakened government. In the year following Shikai’s death, the U.S. deployed forces to Chungking (Chongqing) to protect American lives during this political crisis.

[in-text-ad-2]

1920

Despite siding with the Allies in WWI, China’s efforts in 1919 to reclaim territories held by the Japanese — who were also on the Allied side against the Germans — failed thanks to a secret agreement between Japan, Britain, and France to give these territories to Japan. This sparked a nationalist backlash. In the following year, a U.S. landing force was sent ashore to protect the lives of foreigners during a disturbance in the south-central city of Kiukiang (Jiujiang).

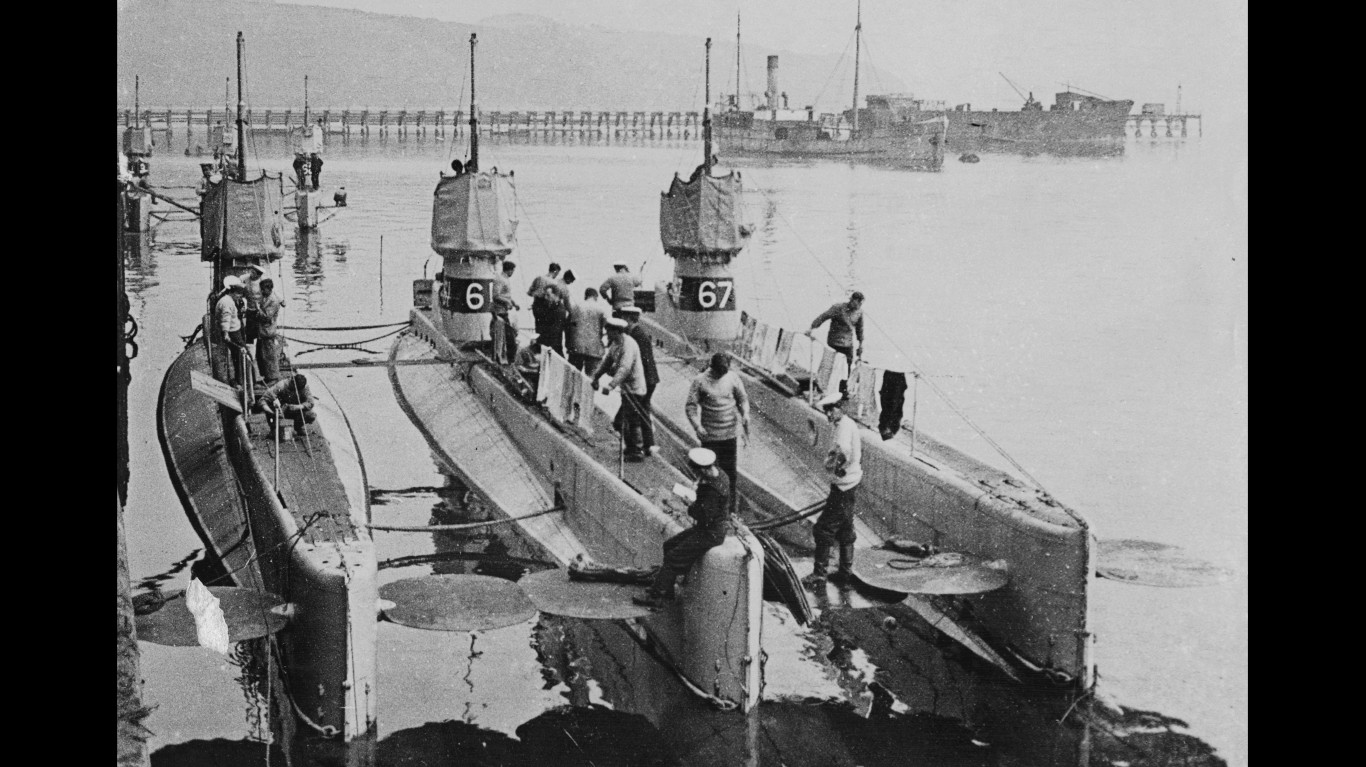

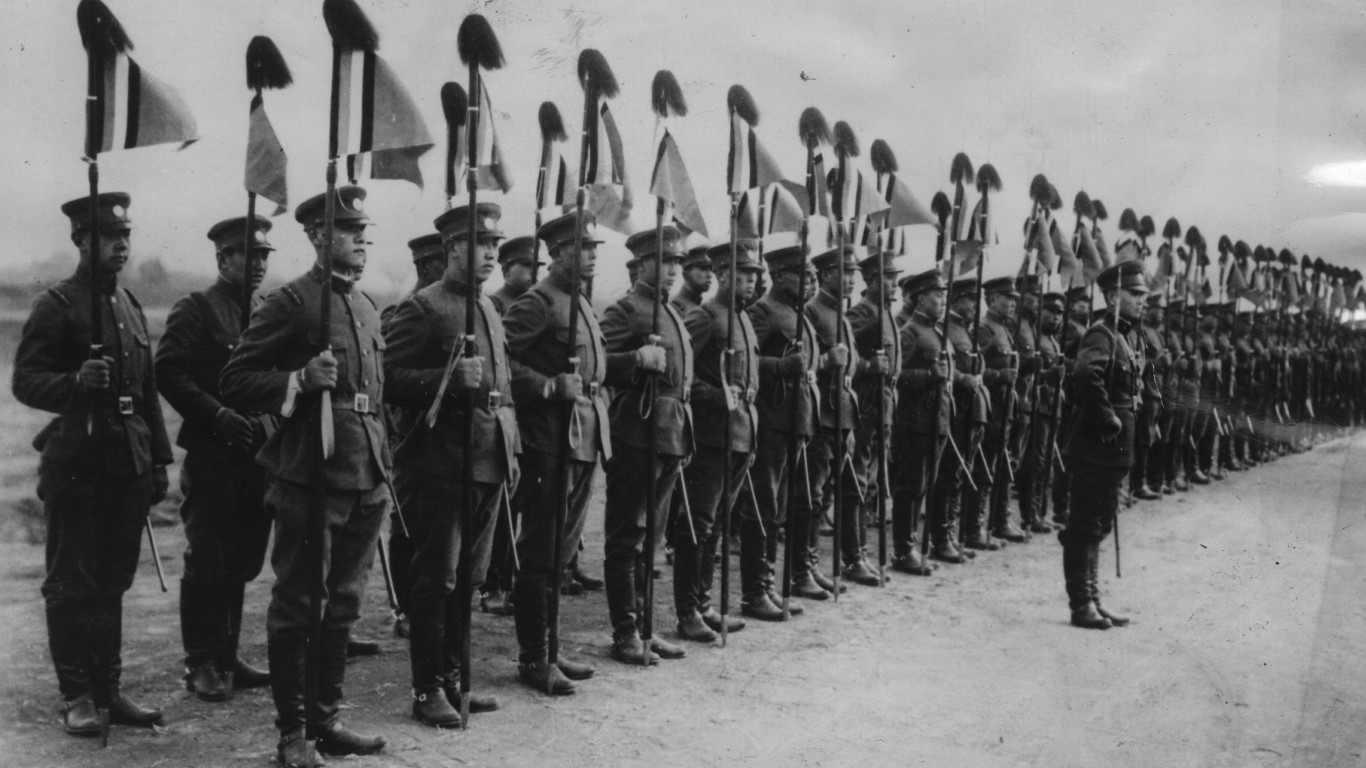

1922-1923

A year after the Chinese Communist Party was established in 1921, the nationalist May Fourth Movement raged on in the wake of WWI related to Japan’s occupation of Chinese territories it took from the Germans and Japan’s horrific treatment of the Chinese during its occupation. From April 1922 to November 1923, U.S. Marines landed in China five times to protect Americans during this period of elevated unrest.

[in-text-ad]

1924

In 1924, the U.S. passed the National Origins Act that included a total prohibition on new immigrants from China and Japan. Meanwhile, China’s anti-foreigner hostilities continued, compelling U.S. Marines to land in Shanghai to protect Americans and other foreigners.

1925

Fighting among Chinese factions, as well as sporadic riots and demonstrations, led to American forces landing again in Shanghai from January to August of 1925 in order to protect the lives of Americans and other foreigners — and to protect properties where foreign nationals lived. On May 30 of that year, Chinese nationalists launched a nationwide movement against foreigners. The death of Sun Zhongshan, known as the country’s “National Father” led to the ascension of Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek) as the leader of the Nationalist Party.

1926

In 1926, Chiang Kai-shek launched his campaign to unite China, operating from his Nationalist Party’s base in the southern city of Guangzhou. Attacks by forces loyal to this movement compelled the U.S. to deploy naval power to protect U.S. citizens.

[in-text-ad-2]

1927

A civil war broke out in China in 1927 and lasted until the end of World War II. The U.S. Navy and Marines increased their presence in Shanghai and Tientsin (Tianjin) and at the American consulate in Nanking (Nanjing) after the Nationalists captured the city in March and declared it their capital. U.S. citizens and other foreign nationalists were killed during the fighting, and, at one point, U.S. and British destroyers used their big guns to protect Americans and other foreigners.

1932

In 1931, the Japanese Army detonated explosives at a rail line near the northern city of Shenyang (Mukden) and used this as a pretense to take over all of Manchuria (the northeast region of China), inciting a global backlash and Japan’s exit from the League of Nations, the predecessor to the U.N. Amid this turmoil, U.S. forces were deployed in 1932 to protect American interest during the Japanese occupation of Shanghai.

[in-text-ad]

1934

As the Communists broke out of their stronghold in the mountains of southern Jiangxi Province, which had been encircled by the Nationalists, U.S. Marines landed at Foochow (Fuzhou) to protect the American consulate. Meanwhile, Mao Zedong was consolidating his power in the Communist Party and its army despite massive losses in their march to the north-central city of Yan’an, in Shaanxi Province.

1945

The end of WWII also ended the Second Sino-Japanese War that had been raging since 1937. The Chinese civil war that began in 1927 would continue until 1949 after the Nationalists were routed and the Communists established the People’s Republic of China. In October 1945, there were about 110,000 U.S. forces in China, including 50,000 U.S. Marines assisting the Nationalists in disarming and repatriating Japanese forces and controlling ports, railroads, and airfields.

1948-1949

By 1948, the Chinese Nationalists were hit with a series of defeats by the Communists that led to the creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. During this bloody transition, U.S. Marines were deployed to Nanking (Nanjing) to protect the American embassy as the Communists rolled in, and to Shanghai to help evacuate Americans.

[in-text-ad-2]

1954-1955

The Korean War solidified antagonism between the U.S. and China and tensions between the Nationalists who had fled to islands, including Taiwan, and the communist Mainland. As the Korean War ended in stalemate (a war that technically has never ended) in the divided Korean Peninsula in 1953, the U.S. put its support behind the Nationalists, the root of today’s tensions between China and the U.S. over Taiwan. In the last U.S. military operation on Chinese soil, the U.S. Navy was deployed to help evacuate U.S. citizens and military personnel from the Tachen (Dachen) Islands off the coast of Taizhou in the East China Sea.

Are You Ahead, or Behind on Retirement? (sponsor)

If you’re one of the over 4 Million Americans set to retire this year, you may want to pay attention.

Finding a financial advisor who puts your interest first can be the difference between a rich retirement and barely getting by, and today it’s easier than ever. SmartAsset’s free tool matches you with up to three fiduciary financial advisors that serve your area in minutes. Each advisor has been carefully vetted, and must act in your best interests. Start your search now.

Don’t waste another minute; get started right here and help your retirement dreams become a retirement reality.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.