According to Transparency International‘s 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), most countries today are failing to stop public corruption. This strongly suggests that institutions designed to thwart bad behavior are failing to do so, leading to an erosion of public trust – and to a proliferation of fraudulent behavior, especially on the part of business leaders and political figures. (These are the countries where government officials accept the most bribes.)

24/7 Tempo has compiled a list of the biggest financial frauds and scandals of the 21st century, drawing information from the U.S. Department of Justice, SHRM, Global Voices, the Council on Foreign Relations, and various media sites. We used editorial discretion to determine the breadth of the scandal based on who was implicated; the amount of money involved; the duration of the episode; and the fallout from the event.

Our research found examples of financial fraud, including money laundering, embezzlement, bribery, and other forms of corruption, on a governmental level in Asia, Africa, Europe, Australia, and North America. Former national leaders of the Maldives, Brazil, Guatemala, and Malaysia were convicted for their roles in corruption in their respective countries. U.S. politicians were not immune: Former Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich, for instance, tried to sell the vacant U.S. Senate seat of then-President-elect Barack Obama and was impeached and convicted for his efforts. (See the worst corruption scandal in each state.)

Click here to learn about the biggest financial frauds and scandals of the 21st century.

Bribery was prevalent in the private sector as well. The 2015 FIFA corruption scandal involved an investigation into bribes, kickbacks, and other illicit activities within the international soccer governing body. The college admissions scandal investigated under the name “Operation Varsity Blues,” was a scheme to gain privileged students’ admission to prestigious colleges and raised concerns about fairness and equity. German technology Siemens engaged in widespread bribery in order to get contracts around the world.

One thing virtually all these episodes have in common is…money – as in efforts to get and/or keep it illicitly.

WeWork meltdown

> When it happened: August 2019

The WeWork scandal of 2019 involved the rapid downfall of the co-working giant due to mismanagement and questionable leadership by founder and CEO Adam Neumann. The company’s valuation plummeted amid concerns over its unsustainable business model, corporate governance issues, and lavish spending. The scandal highlighted the risky nature of its aggressive expansion strategy and exposed Neumann’s reckless behavior and dubious decisions.

[in-text-ad]

Wells Fargo fake accounts

> When it happened: September 2016

The bank was found guilty of widespread fraudulent sales practices, where employees opened millions of unauthorized accounts to meet unrealistic sales targets. The unethical actions resulted in customer harm, as fees were charged for these accounts without consent. The bank agreed to pay $3 billion to resolve criminal and civil investigations.

LIBOR interest rate scandal

> When it happened: June 2012

The LIBOR scandal of 2012 revolved around the manipulation of the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), a benchmark interest rate affecting global financial products. The scandal emerged when major banks were revealed to have falsified their borrowing costs to influence LIBOR, impacting trillions of dollars in transactions. This manipulation had widespread implications, affecting interest rates for mortgages, loans, and derivatives. Regulatory authorities imposed more than $9 billion in fines on implicated banks. The scandal exposed systemic flaws in financial benchmarks.

FIFA bribery scandal

> When it happened: May 2015

In the FIFA scandal, officials were accused of soliciting and accepting bribes for awarding lucrative World Cup hosting rights and marketing deals dating back to the early 1990s. The investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice centered on the scheme involved in awarding the 2018 World Cup to Russia and the 2022 World Cup to Qatar. The scandal led to the arrest and indictment of numerous high-ranking FIFA officials and executives, and highlighted the culture of corruption and lack of transparency within the organization.

[in-text-ad-2]

Drug price gouging

> When it happened: September 2015

In 2015, Martin Shkreli, a onetime hedge fund manager and the CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, sparked outrage when he marked up the price of the life-saving antimalarial and antiparasitic drug Daraprim, often used to treat AIDS patients, almost 56 times, from $16.50 to $750 per pill. Shkreli defended the price hike, claiming it was necessary for profitability. However, he faced intense backlash from the public, medical professionals, and lawmakers. Though he was subsequently banned from the pharmaceutical industry for life, he was accused of no crimes in the affair. However, he was subsequently arrested and convicted for securities fraud in an unrelated case, ordered to forfeit more than $7 million in assets, and sentenced to a seven-year prison term. (He was released last year.)

Theranos deception and fraud

> When it happened: October 2015

The Theranos scandal involved founder Elizabeth Holmes and her blood-testing startup, which she launched at age 19. Holmes claimed to have developed revolutionary technology capable of conducting numerous tests with a few drops of blood. However, investigations revealed inaccuracies and reliability issues. In 2018, Holmes and former Theranos president (and Holmes’s married lover) Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani were charged with fraud for misleading investors and patients. They faced accusations of fabricating test results, thus endangering lives. The case highlighted corporate deception, and Holmes faced a high-profile trial for multiple charges. Holmes was sentenced to 11.3 years in prison after being convicted of fraud and conspiracy. Balwani was sentenced 12 years and 11 months in federal prison plus three years of probation for fraud. Holmes and Balwani were also ordered to pay $452 million in restitution to victims of their scheme, sharing the costs between them. The scandal exposed the dangers of prioritizing innovation hype over scientific rigor.

[in-text-ad]

College admissions scandal

> When it happened: March 2019

The college admissions scandal, investigated by an FBI initiative known as “Operation Varsity Blues,” saw William “Rick” Singer orchestrating a bribery scheme in which he and his co-conspirators won wealthy students admission to prestigious universities including Yale, UCLA, Georgetown, and Stanford. Singer manipulated standardized test scores and athletic credentials, exploiting his “side door” access to the schools. In 2023, Singer was sentenced to three-and-a-half years in prison, three years of supervised release, and a fine of $10 million on charges of conspiracy, money laundering, and obstruction of justice. High-profile individuals, including celebrities such as actresses Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman, were implicated. The scandal highlighted disparities in the admissions process, underscoring concerns over fairness and equity.

Opioid makers corruption

> When it happened: November 2019

Purdue Pharma admitted guilt in 2020 for fraud and kickback conspiracies, acknowledging its role in fueling the opioid epidemic in the U.S. The company aggressively marketed OxyContin, downplaying its addictive nature and overstating its benefits, contributing to widespread opioid addiction and overdose deaths. The company was also accused by members of Congress of corruptly influencing the World Health Organization in order to increase its painkiller sales across the globe. Purdue filed for bankruptcy and faced extensive litigation for its actions. The Sackler family, which owns the company, eventually agreed to establish a $6 billion fund to pay restitution to opioid victims, their families, and numerous state governments, in return for being shielded from personal lawsuits. This month, the Biden administration appealed the terms of the settlement, believing that the Sacklers should face lawsuits as well. The Supreme Court will hear the case in December. Purdue Pharma’s practices exemplified the larger issue of pharmaceutical companies’ influence over health care policies and opioid prescription practices.

Venezuela currency scandal

> When it happened: 2014

The Venezuela currency scandal of 2014 involved a massive money-laundering scheme. Two financial asset managers were charged for their alleged involvement in laundering about $1.2 billion out of Venezuela. The plot involved officials, the Venezuelan elite, and professional third-party money launderers, and exploited the country’s complex currency controls and exchange rate differentials. The scandal revealed how corrupt individuals capitalized on Venezuela’s economic instability, exacerbating its financial crisis.

[in-text-ad-2]

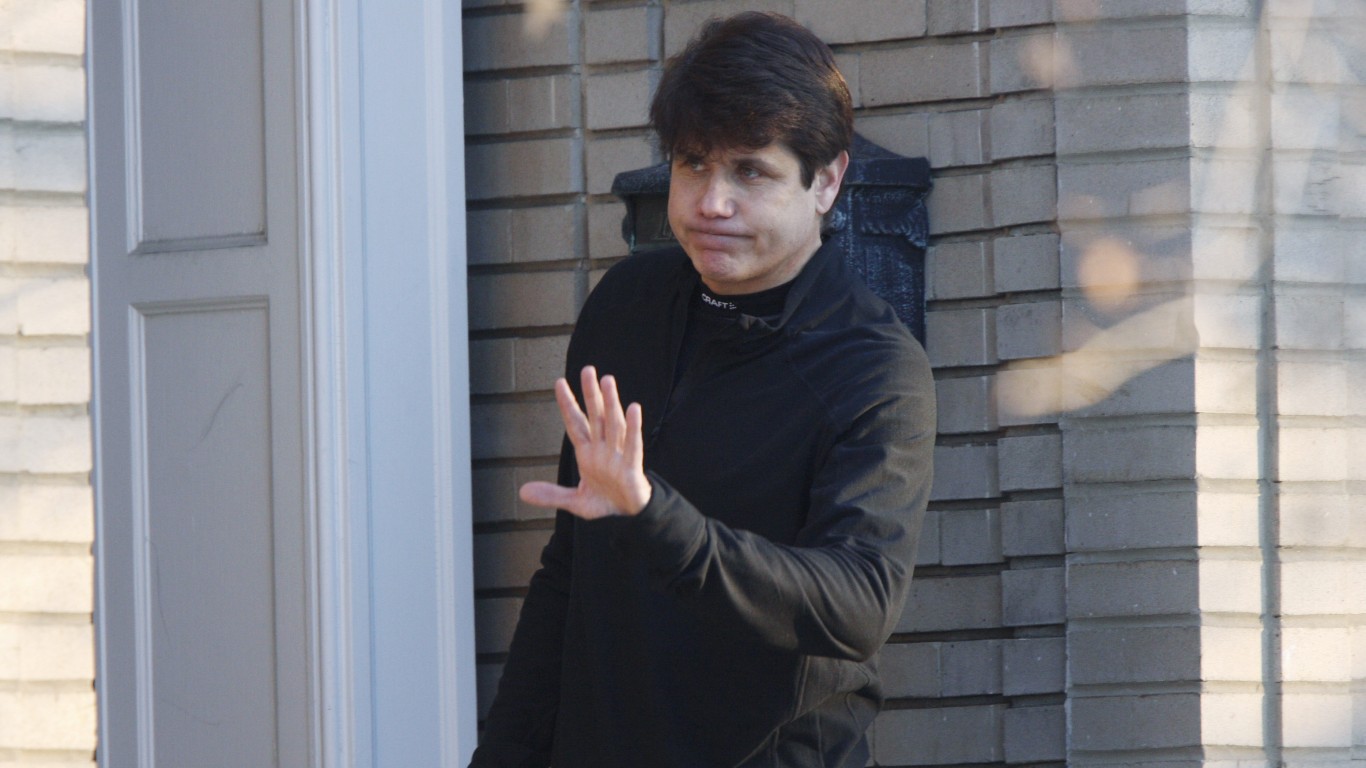

Attempted sale of a U.S. senate seat

> When it happened: 2012

Rod Blagojevich, then the governor of Illinois, was the center of a political scandal for attempting to sell the vacant U.S. Senate seat of then-President-elect Barack Obama. Blagojevich was captured on wiretaps discussing potential deals and seeking financial or political benefits in exchange for the appointment. He was impeached and removed from office in 2009. In 2011, he was convicted on corruption charges, including attempting to trade the Senate seat for campaign donations. The scandal led to a 14-year prison sentence for Blagojevich – a sentence later commuted by then-president Donald Trump.

Gupta family ‘capture’ of South Africa

> When it happened: 2016

The Gupta family’s scandal in South Africa centered around brothers Ajay, Atul, and Rajesh Gupta and their undue influence over President Jacob Zuma’s administration from 2009 to 2018. Through close personal ties with Zuma, the Guptas manipulated appointments of at least 10 ministers and several senior officials to benefit their wide-ranging business interests in IT, mining, media, and other sectors. Their web of corruption implicated major firms like McKinsey, KPMG, and other international companies in illicit deals worth more than $7 billion. Dubbed the “state capture scandal,” it revealed deep vulnerabilities in South Africa’s government institutions and highlighted the need for transparency and accountability measures to prevent corporate control of the state decision-making apparatus.

[in-text-ad]

Siemens bribes

> When it happened: 2006

Siemens, a leading German technology conglomerate, was found to have engaged in widespread bribery involving payments of about $1.4 billion from the early 1990s to 2006, in order to secure contracts around the world. The corrupt acts occurred notably in Argentina, Bangladesh, and Venezuela as Siemens paid off government officials and others to win infrastructure and energy deals. When exposed in 2006, the scandal tainted Siemens’ reputation and resulted in one of the largest settlements ever under the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, amounting to $1.6 billion in fines and penalties. The Siemens case highlighted the extensive bribery prevalent in global corporate dealings.

Corrupt tourism

> When it happened: 2018

Corruption’s detrimental effects on Maldives’ tourism industry made headlines in 2018. Dubbed “corrupt tourism,” practices included questionable land allocation, permits, and infrastructure development, contributing to environmental harm. These issues have tarnished the nation’s reputation as a pristine vacation spot. In a significant development, in December of last year, a Maldivian court convicted former President Abdulla Yameen for corruption, underscoring concerns about governance.

Offshore tax avoidance

> When it happened: 2017

The offshore Bermuda-based law firm Appleby, founded in 1898, was the source of more than 13 million electronic documents leaked by hackers to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung (which had previously been given the notorious Panama Papers). The German publication in turn made the documents widely available. The leak revealed complex offshore structures and questionable dealings by corporations and individuals. In one example, offshore secrecy put commodities company Glencore in a position to bribe the former president of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Joseph Kabila, while it negotiated for mining licenses. Appleby denied any wrongdoing, but the scandal prompted global scrutiny of offshore financial practices, sparking debates on transparency, ethics, and the role of such firms in enabling illicit financial activities.

[in-text-ad-2]

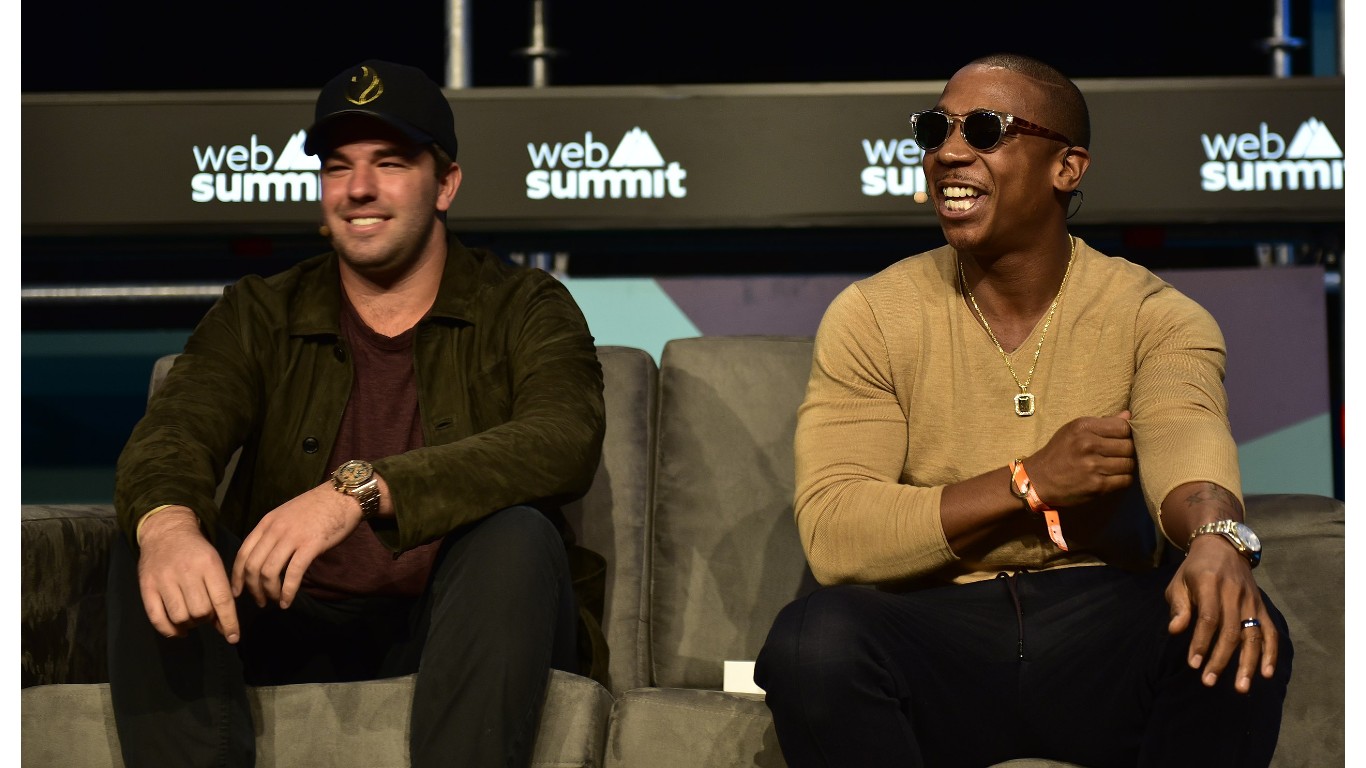

Phony festival

> When it happened: April 2017

The Fyre Festival scandal involved conman Billy McFarland, who scammed investors out of $26 million by promising an extravagant festival experience set in the Bahamas, featuring supermodels like Emily Ratajkowski and Bella Hadid, A-list musical talent, and gourmet food. Tickets for the event, which was launched in collaboration with rapper Ja Rule, were sold for hundreds of dollars, up to as much as $12,000, but when attendees arrived, they found basic tents instead of luxury accommodations, pre-made sandwiches instead of culinary delicacies, and no infrastructure, and artists supposedly on the program – including Little Yachty, Blink-182, Migos, Tyga, and Pusha T – had all pulled out before the event. Once the dust had settled from this disaster, McFarland was convicted of fraud and sentenced to prison for six years. Ja Rule was not charged. In 2023, reports emerged that McFarland was attempting to relaunch the festival despite his criminal record. The scandal highlighted the dangers of fraudulent marketing, and its aftermath underscored the legal consequences of such schemes.

Brazil’s network of corruption

> When it happened: 2014

The Operação Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash) scandal in Brazil was a massive corruption investigation involving the state-owned Petrobras oil company and numerous high-ranking politicians, contractors, and business figures. The scandal exposed a vast web of bribery, kickbacks, and money laundering. It led to the imprisonment of 150 individuals, including three former presidents of the country – Michel Terner, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and Fernando Collor de Mello. Operation Car Wash – so named because the first part of the investigation, before the extent of the corruption was known, concerned a car wash in Brasília – sparked protests and political upheaval, shaking Brazil’s economy and governance. This extensive case has been hailed as one of history’s largest corruption scandals. The Brazilian government dissolved the anti-corruption task force in February 2021. Then-president Jair Bolsonaro claimed the task force was no longer needed as corruption had been eradicated from the government. However, some analysts believe the real motive was that Bolsonaro feared the investigation could target him or his family members next.

[in-text-ad]

The Troika Laundromat

> When it happened: 2006-2013

The so-called “Troika Laundromat” was a sub rosa network of offshore banks organized by a private Russian investment bank called Troika Dialog – subsequently bought by the country’s state-owned Sberbank. Troika created at least 75 shell companies in various tax havens to issue and cancel fake contracts and loans with the aim of helping its clients launder money and evade taxes. An estimated $4.6 billion passed through the Laundromat to enter the international financial system. Much of the laundering was done through Lithuania’s Ūkio Bankas. After an investigation was launched in 2019 by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, several of the principals in the scandal were mysteriously killed. Numerous nations subsequently imposed sanctions on Sberbank, and it is now out of business in most of the world.

Czech PM under fire

> When it happened: 2018

Andrej Babiš, a wealthy businessman, entered politics and became the prime minister of the Czech Republic from 2017 to 2021. The European Commission conducted an investigation and confirmed that Babiš had maintained control over Agrofert, a major conglomerate involved in agriculture, food, chemicals, and media, even after supposedly transferring ownership to trust funds to comply with the law. This raised concerns about the potential for using his political position to benefit his private businesses, which could compromise fair competition and misuse EU funds. Babiš faced protests, calls for his resignation, and accusations of undermining democratic principles, but he remained in power. He was also accused of concealing his ownership of properties bought through an offshore company, and of various conflicts of interest. He was officially cleared of fraud in January 2023, but lost his presidential bid in January.

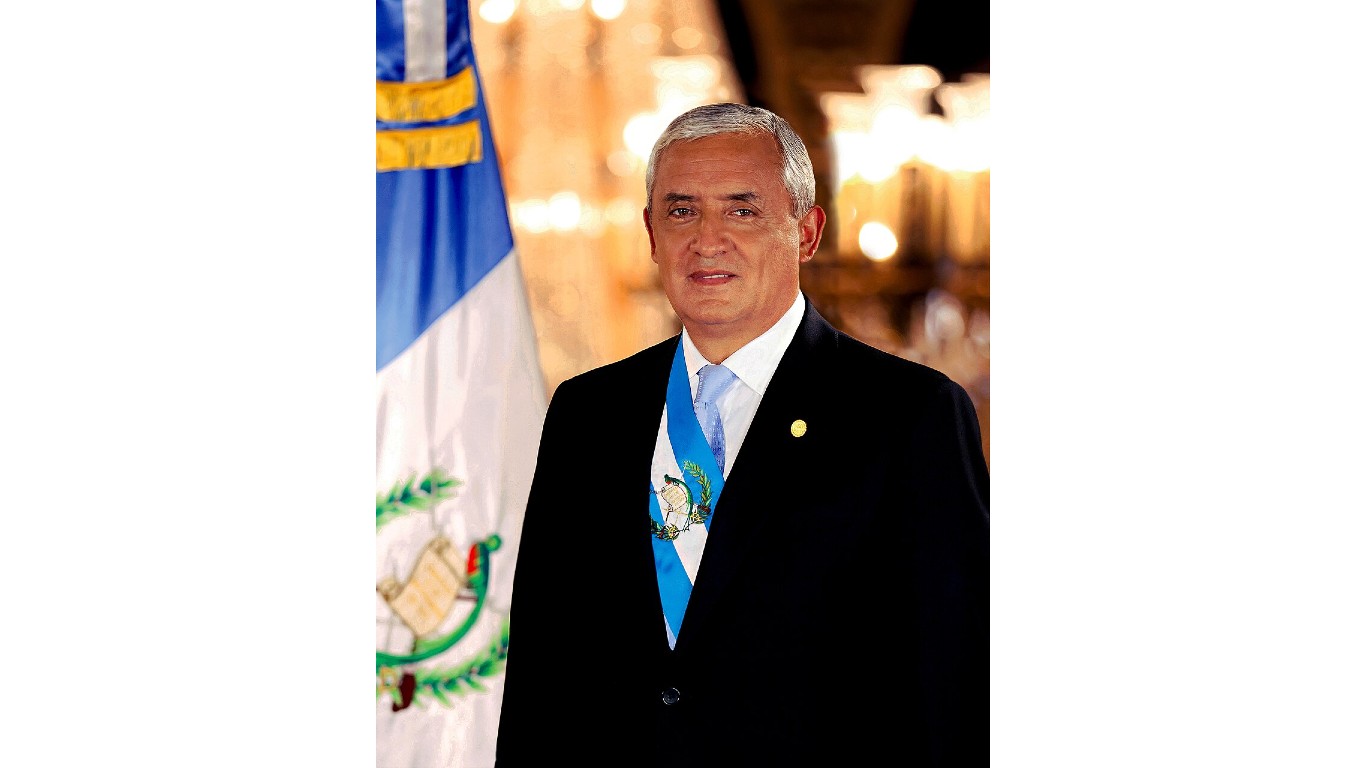

Guatemala corruption crisis

> When it happened: 2019

In 2015, an investigation by the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) of then-president Otto Pérez Molina led to his resignation and later trial and conviction on corruption charges, resulting in a sentence of 16 years in prison. He was also accused of committing atrocities during Guatemala’s civil war and of possible political assassinations, but never charged. Molina’s successor, former comedian Jimmy Morales, ran his campaign promising to fight corruption, but unilaterally canceled an agreement with the United Nations allowing CICIG to operate in Guatemala after it began investigating corruption allegations against him and his campaign for taking illegal donations. His older brother and one of his sons were arrested on charges of money laundering and corruption in 2017, and there was pressure on the government to arrest Morales himself after he left office in 2020. He failed in his bid for a seat in Congress this year.

[in-text-ad-2]

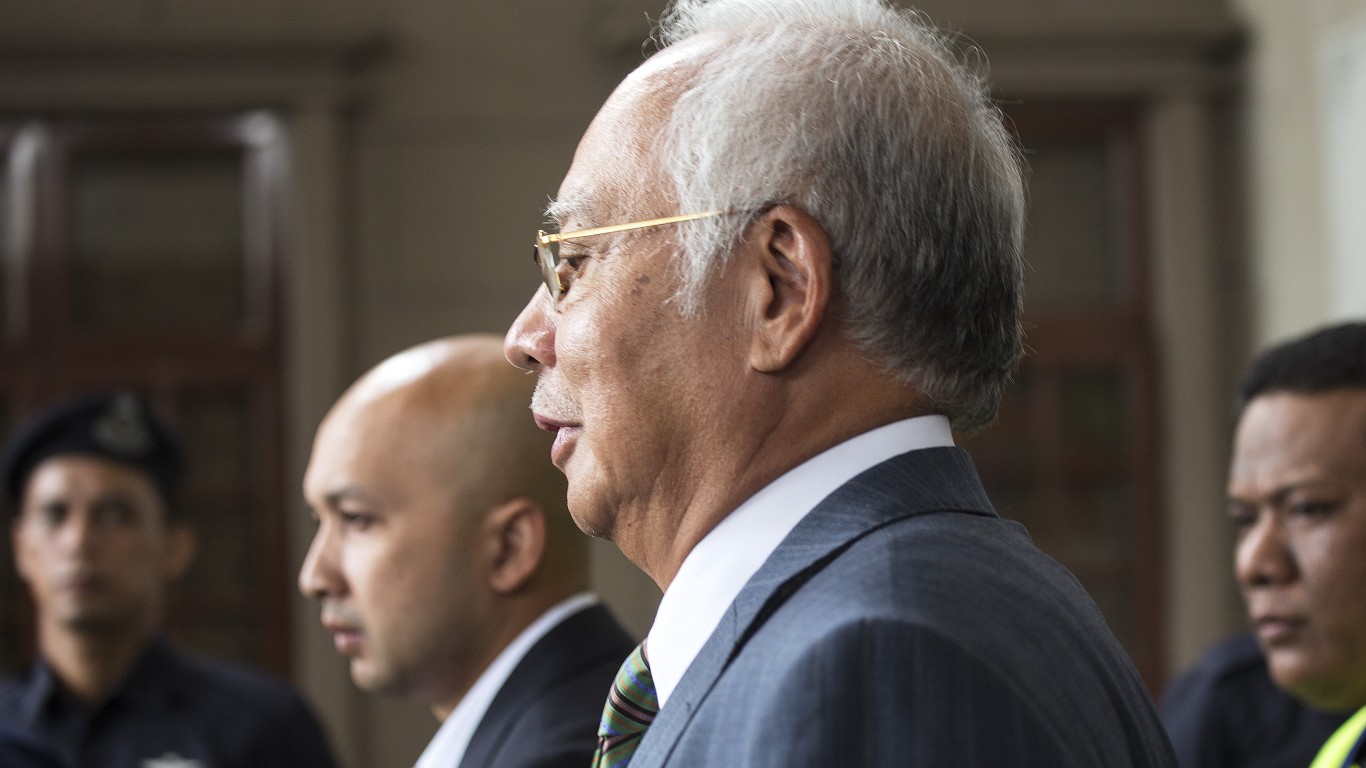

Malaysia 1MDB scandal

> When it happened: 2009

The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) scandal was a massive financial controversy centered on Malaysia’s state investment fund, which had been set up to improve the country’s economy through strategic investments. Billions of dollars were allegedly embezzled through a complex network of shell companies and transactions. High-profile figures, including former prime minister Najib Razak, who chaired the fund, were implicated in misappropriating funds for personal gain, luxury purchases, and extravagant events. Najib, who was accused of channeling more than $700 million into his personal bank accounts, was arrested in 2018 on charges of money laundering and abuse of power and is now serving a 12-year prison term.

Australia’s corrupt bureaucrat

> When it happened: 2021

Paul Whyte, a West Australian bureaucrat, was sentenced to 12 years in jail for orchestrating a scheme, dubbed “Australia’s single biggest case of public sector fraud,” to steal $27 million AUD (about $20,250,000 USD) of taxpayer money. Whyte, while a senior public servant overseeing public housing, used a fake invoice scheme through shell companies to misappropriate funds over an 11-year period. He spent the stolen money on a lavish lifestyle, including gambling, racehorses, and a riverside mansion. He is now serving a 12-year prison sentence.

[in-text-ad]

Bernie Madoff

> When it happened: Decades ending in 2009

Bernie Madoff was an American money manager who created the largest Ponzi scheme in financial history. He defrauded thousands of investors – including nonprofits such as the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Peace – out of billions of dollars over many decades before he was apprehended in 2008.

Madoff attracted investors by claiming to generate large, steady, returns – that were ultimately fictitious. He covered investors’ withdrawals by funding redemptions through the funds of new investors. Madoff’s scheme collapsed in 2008 during the financial crisis. In 2009, Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison and forfeited $170 billion as restitution. He died in prison in 2021.

The Average American Has No Idea How Much Money You Can Make Today (Sponsor)

The last few years made people forget how much banks and CD’s can pay. Meanwhile, interest rates have spiked and many can afford to pay you much more, but most are keeping yields low and hoping you won’t notice.

But there is good news. To win qualified customers, some accounts are paying almost 10x the national average! That’s an incredible way to keep your money safe and earn more at the same time. Our top pick for high yield savings accounts includes other benefits as well. You can earn up to 3.80% with a Checking & Savings Account today Sign up and get up to $300 with direct deposit. No account fees. FDIC Insured.

Click here to see how much more you could be earning on your savings today. It takes just a few minutes to open an account to make your money work for you.

Our top pick for high yield savings accounts includes other benefits as well. You can earn up to 4.00% with a Checking & Savings Account from Sofi. Sign up and get up to $300 with direct deposit. No account fees. FDIC Insured.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.