Special Report

32 Haunting Photos That Capture the Struggles of the Great Depression

Published:

The Great Depression was a dark time in U.S. history, a worldwide economic downturn that began in 1929 and lasted a decade – the longest and most severe depression ever experienced by a country in the industrialized world. (See what the stock market was worth the year you were born.)

Nothing brings to life the privations of the period and the sheer desperation felt by those who had to suffer through it like photographic images taken at the time.

To assemble an album of haunting images from the Great Depression, mostly taken in America, 24/7 Tempo combed through the photo archives of Getty Images and the Library of Congress. Information about the Great Depression came from sources including the New York Times, History, and Britannica.

Before the crash of the stock market on Oct. 29, 1929 – which became known as Black Tuesday – the unemployment rate in the U.S. was 3.2%. In 1933, in the depths of the Depression, it soared to about 25%. (In our own time, these are the 15 states with the worst spikes in unemployment since the pandemic.)

People tried to find work and help each other in various ways. Charitable organizations opened soup kitchens and breadlines to feed the hungry, and the government, led by a new president – after the former one refused to supply aid because he believed in self-reliance – created various agencies to employ people in public works.

Despite all of these efforts, the Depression lingered until 1939, and its effects were still being felt years afterwards.

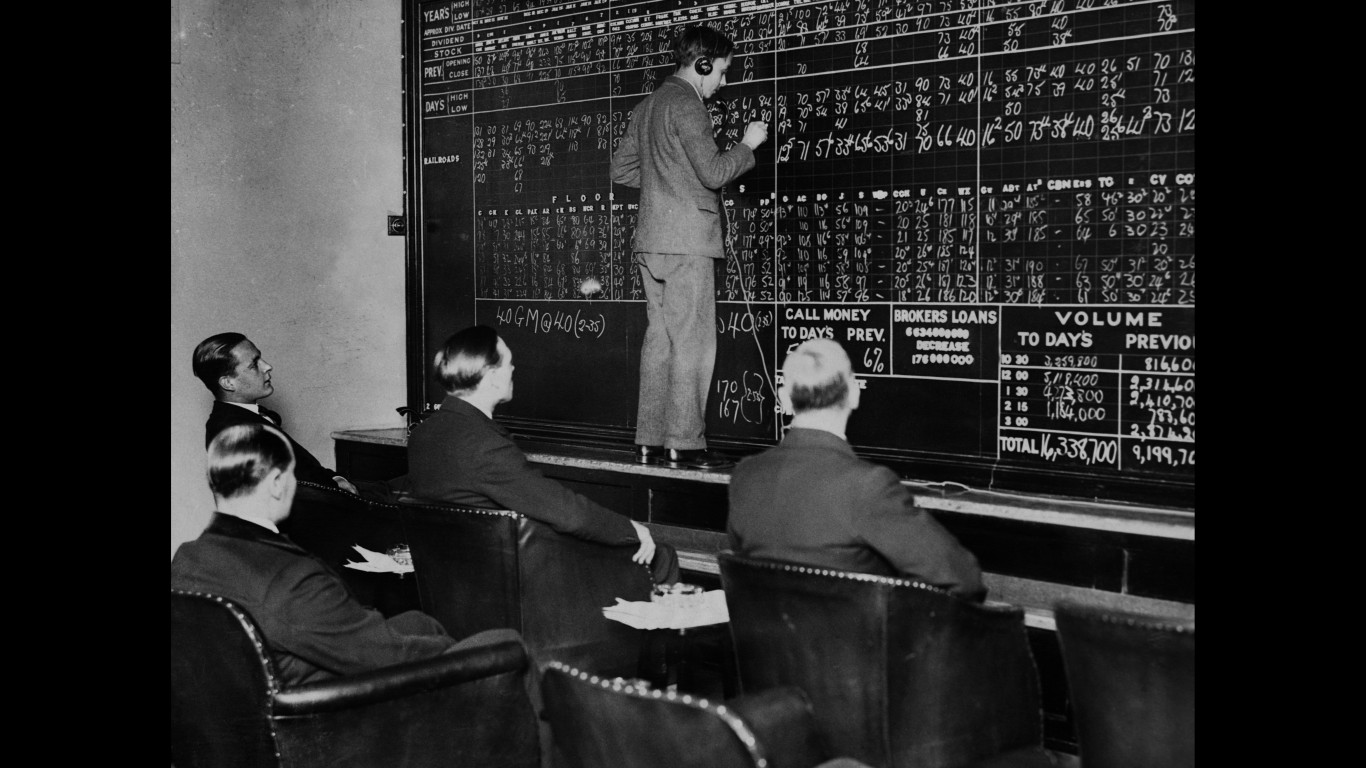

Outside the Stock Exchange (1929)

People gather outside the New York Stock Exchange in downtown Manhattan a few days after the “Black Tuesday” crash, in which investors traded in about 16 million shares, resulting in billions of dollars lost.

[in-text-ad]

Chrysler for sale, cheap (1929)

In one of the most iconic Depression-era photos, bankrupt modeling agent Walter Clarence Thornton desperately tries to sell his luxury roadster – a 1928 Chrysler Imperial 75 Roadster – for $100 cash (about $1,735 in today’s dollars).

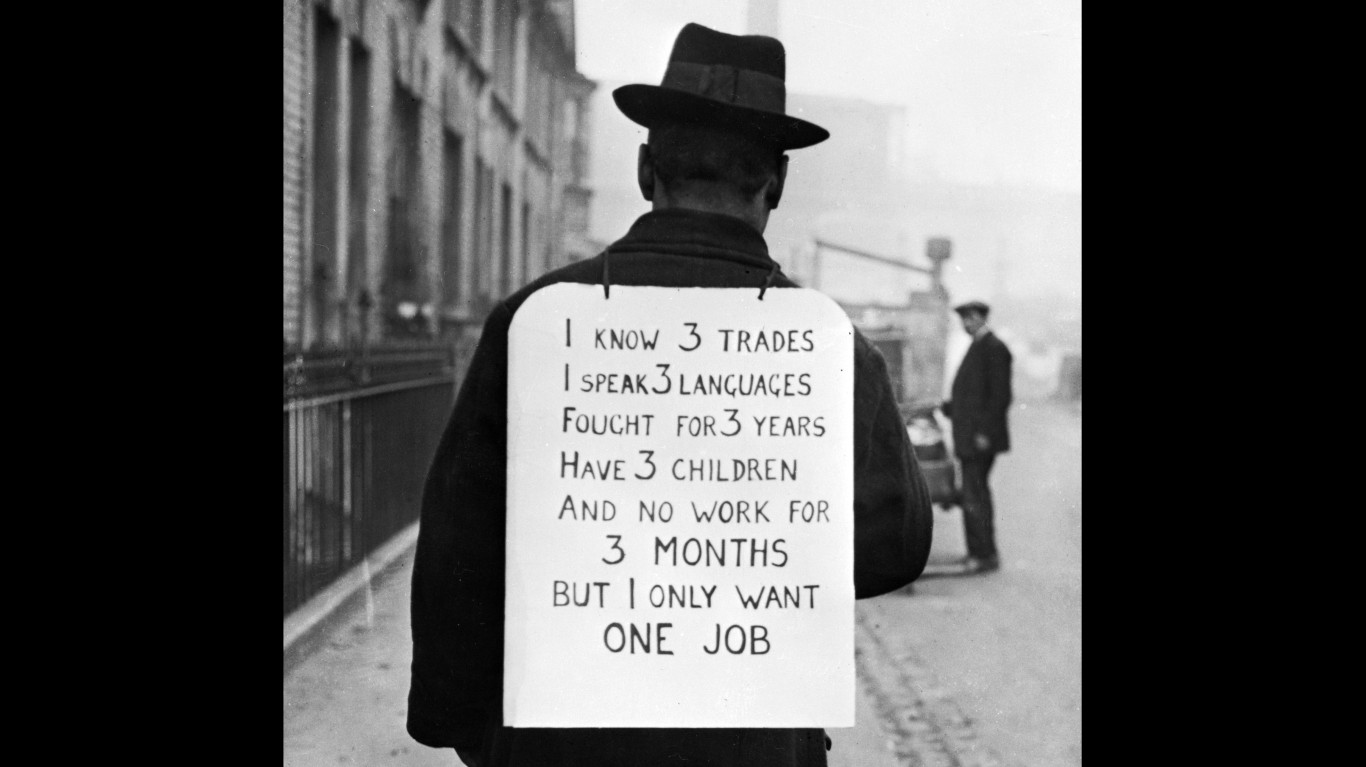

A Hooverville shack (1929)

Several men and a boy stand outside a shack in a shantytown. These homeless camps were known as Hoovervilles, after President Herbert Hoover. who was blamed for the poor economic conditions because he was resistant to government aid and intervention.

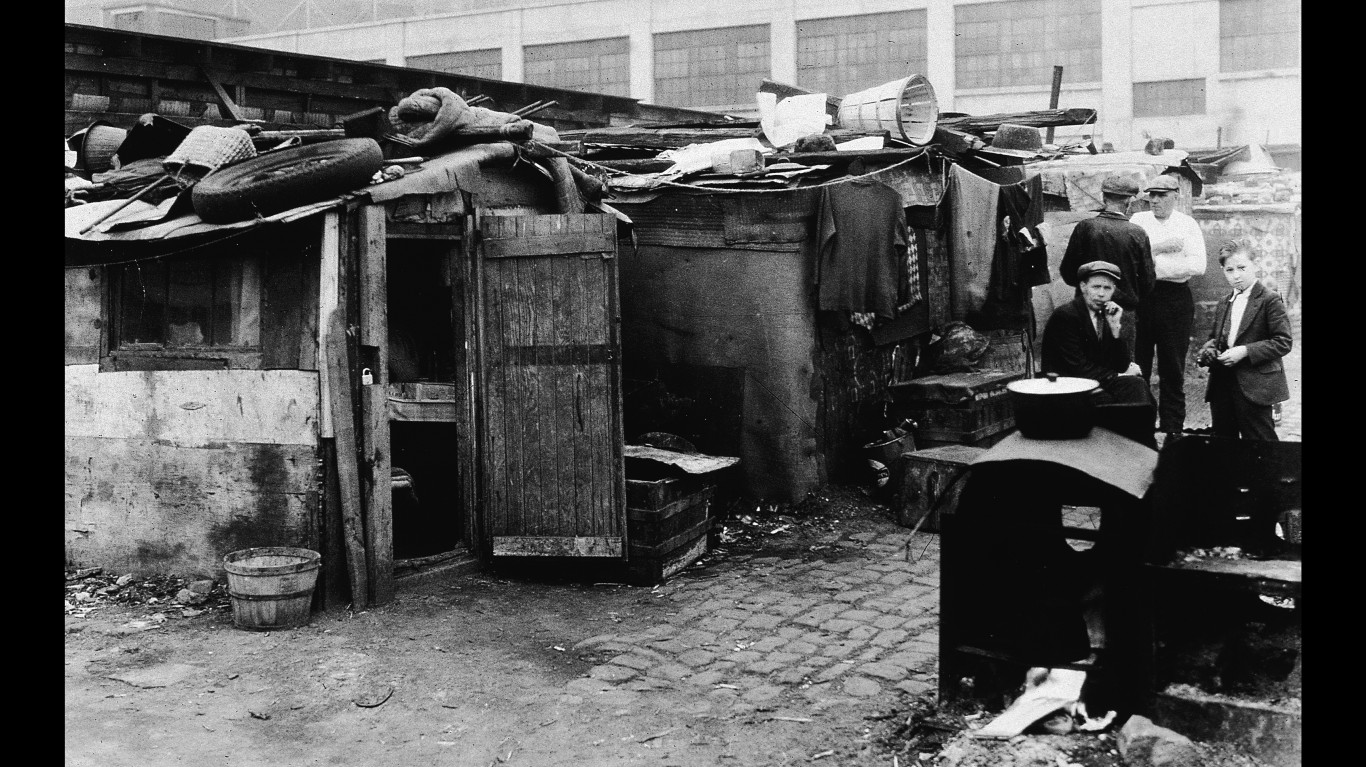

Tracking the market in London (1929)

A young telephone operator at the St. Phalle Ltd. club in London marks the plummeting share value of stocks, received from New York via a telephone headset, on a blackboard, while investors watch to know when to buy and sell.

[in-text-ad-2]

Resting up (1929)

Stockbrokers and their clerks rest or sleep in a gym after working into the early hours of Wednesday, Oct. 30, 1929, following the market crash.

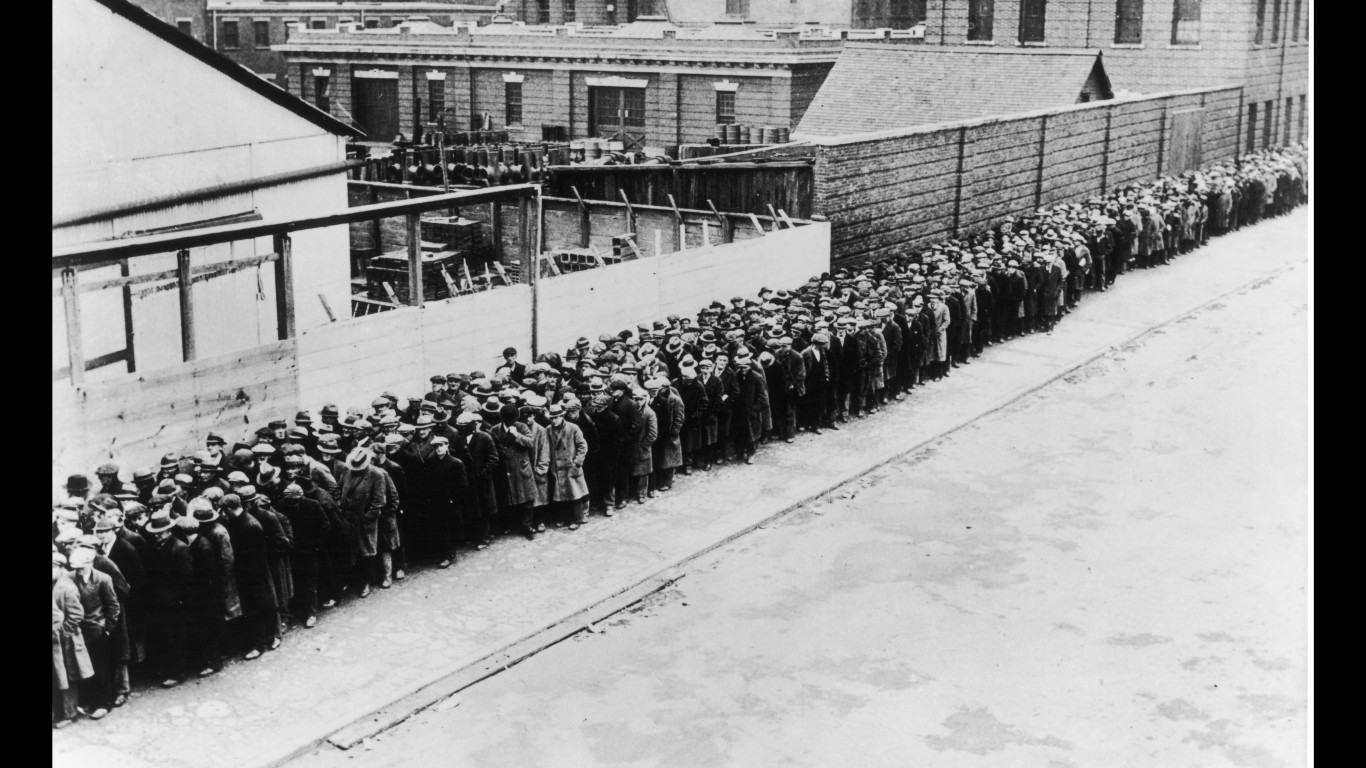

Lining up for dinner (circa 1930)

A lineup of unemployed and homeless people, usually men, waiting outside a municipal lodging house for a free dinner.

[in-text-ad]

Trying to make a living (1930)

In New York, as elsewhere around the country, some people who’d lost their jobs after the market crash tried to make a living by selling apples on the street. Joseph Sicker, chairman of the International Apple Shippers’ Association at the time, gave apples to unemployed people to sell.

At the soup kitchen (1930)

More than a year after Black Tuesday, hungry men of all ages have gather at a Salvation Army soup kitchen. Dolly Gann (left), half-sister of Vice-President Charles Curtis, helps serve the meals.

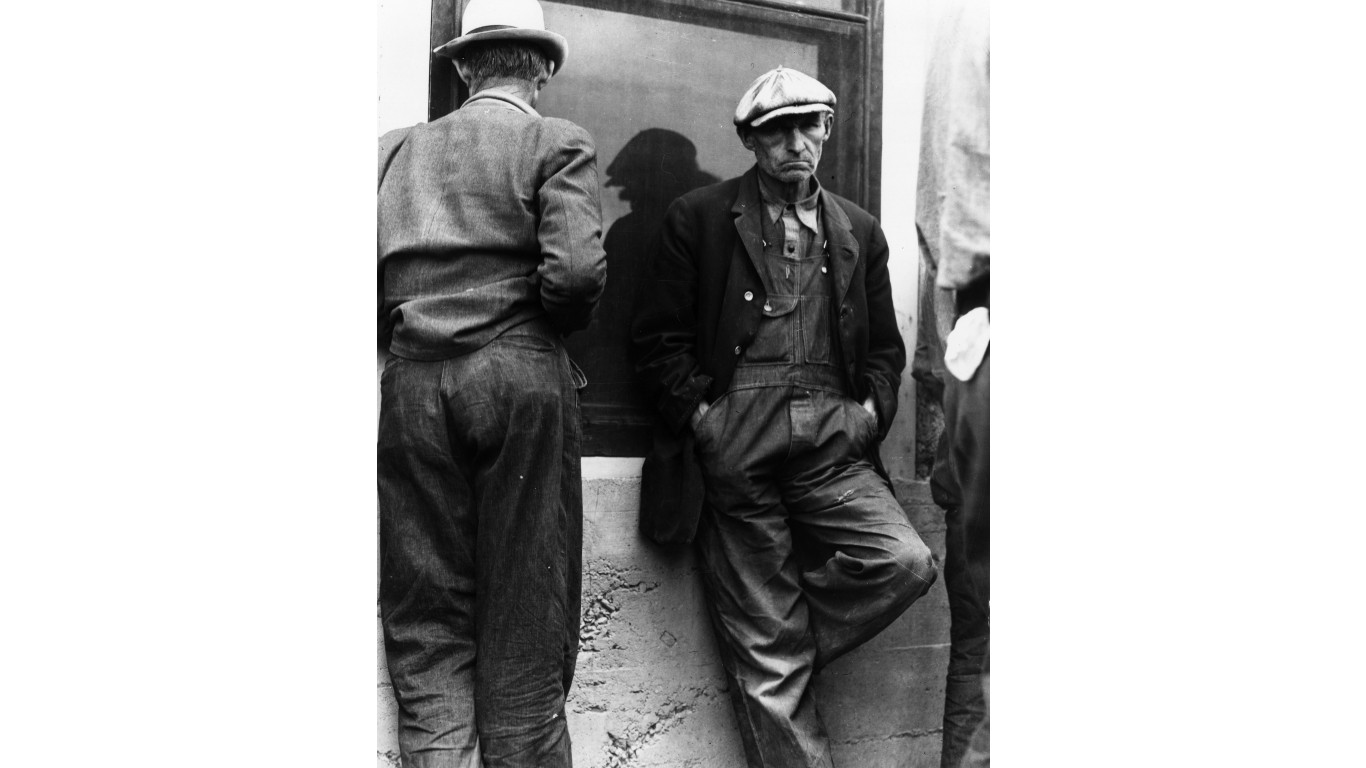

Waiting for work (1931)

Unemployed men gather at a dockyard, hoping to get hired, even if only temporarily.

[in-text-ad-2]

Women hoping for a job (1931)

Women line up on a sidewalk in London, hoping for employment. In the background is the Royalty Theatre – where, ironically, a play called “Money! Money!!” is being performed.

Sleeping where they can (1931)

Unemployed people bed down in the corridors of Philadelphia City Hall to escape the cold at the end of September. Between 1930 and 1931 the number of jobless residents in the city rose from 135,000 to 250,000 – more than a quarter of Philadelphia’s entire workforce.

[in-text-ad]

Keeping the men in line (1931)

A crowd of unemployed men waits outside an Emergency Unemployment Relief registration office, city unknown. Sometimes thousands of people gathered, waiting to register, and riots sometimes broke out – explaining the police presence here.

Unemployment in L.A. (1932)

Thousands of jobless people gather on a Los Angeles street to protest the lack of employment or relief funds. When the police arrive, they arrest group leaders, alleged to be Communist agitators.

Vote for Roosevelt (1932)

New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt is greeted by a large crowd while campaigning in Indianapolis on Oct. 30. Eight days later, he was to be elected president, using his office to create a plan that became known as The New Deal, which had three goals: relief, recovery, and reform.

[in-text-ad-2]

Demanding their bonuses (1932)

Police stop members of the Bonus Expeditionary Force, also known as the Bonus Army, a group of some 17,000 World War I unemployed veterans and their families and supporters, who marched on the nation’s capital to demand full payment of their war bonuses.

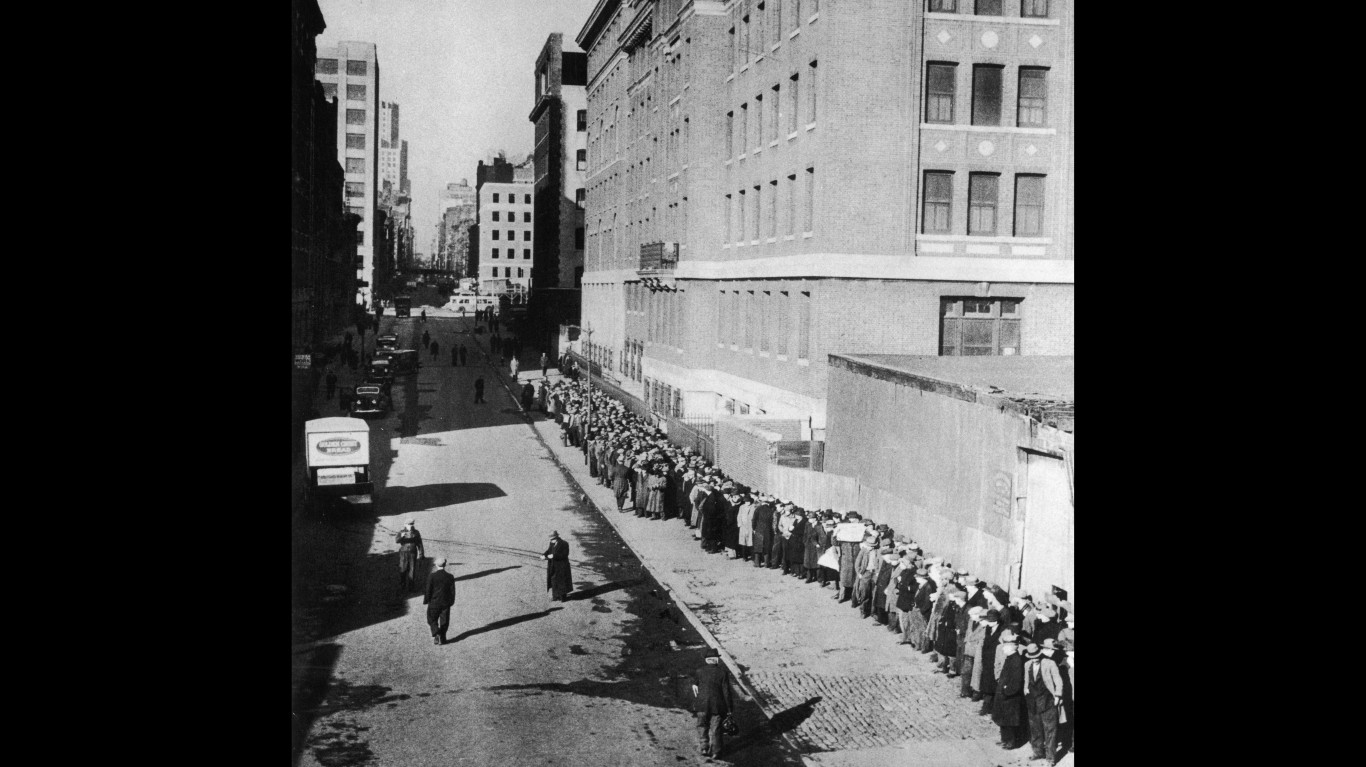

Hoping for city jobs (1933)

Thousands of unemployed men gather in front of the Home Relief Bureau on 23rd Street in New York City waiting to register for city jobs.

[in-text-ad]

Getting lucky in Memphis (circa 1934)

Workers wait for jobs outside the State Unemployment Office in Memphis. Compared to other big cities in the South, Memphis was spared the worst effects of the Depression, as it had a diversified local economy and was a trading center for the region.

On the job in San Francisco (1934)

The Civil Works Administration was a short-lived New Deal job creation program offering manual-labor jobs to millions of unemployed workers. These CWA laborers push wheelbarrows full of dirt to fill a gully during the construction of the Lake Merced Parkway Boulevard.

Happy to be heading off to work (circa 1935)

Men wave as a train pulls out to take them to jobs with the Civilian Conservation Corps, one of the most famous New Deal initiatives – a work relief program that employed young men in environmental projects, which helped the country’s national and state park systems.

[in-text-ad-2]

Children in poverty (circa 1935)

Impoverished children sit outside an Arkansas rehabilitation clinic. Juvenile malnourishment was common during the Depression, and many young children were orphaned.

Desperate for something to eat (circa 1935)

People wait in a bread line in an unidentified city.

[in-text-ad]

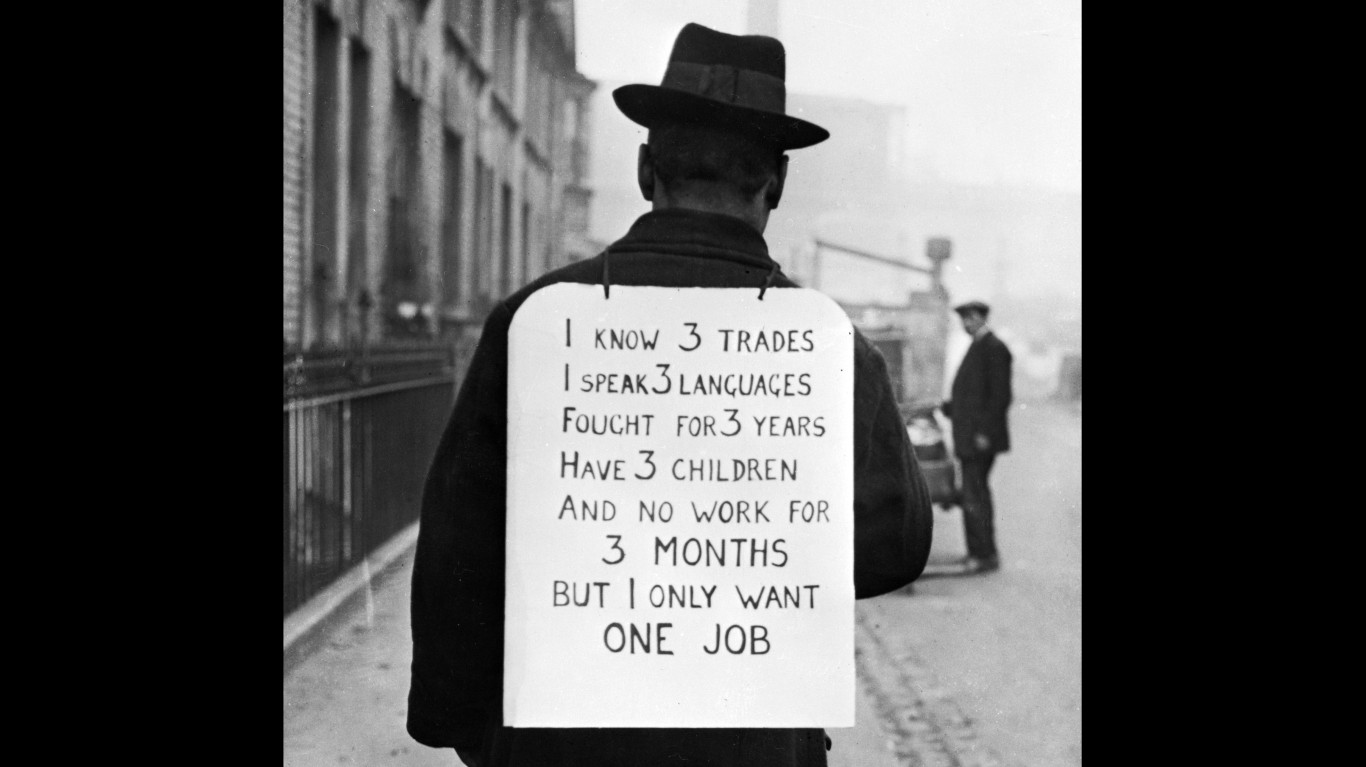

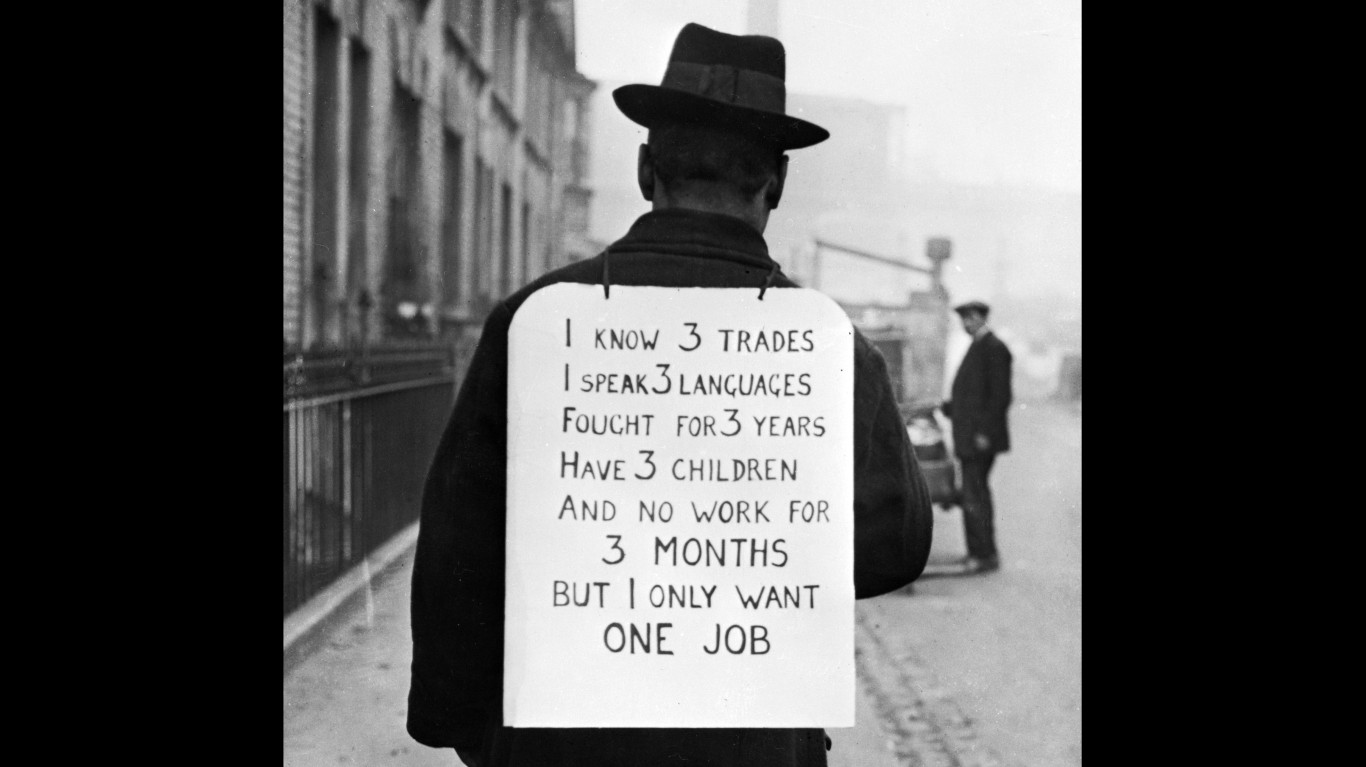

A walking résumé (1935)

In another of the most iconic images from the Great Depression, an unemployed man wears his qualifications on a signboard.

Soup and bread (1935)

Unemployed men eating a free meal of soup, bread, and coffee at Bernarr Macfadden’s Penny Cafeteria, a vegetarian restaurant in Manhattan. Macfadden was an early advocate of bodybuilding and healthy eating, and established the Macfadden Foundation, which opened schools, physical training centers, and restaurants for the unemployed.

Time to relax (circa 1935)

Men working on a New Deal public works project in an unidentified location take a break for some horseplay.

[in-text-ad-2]

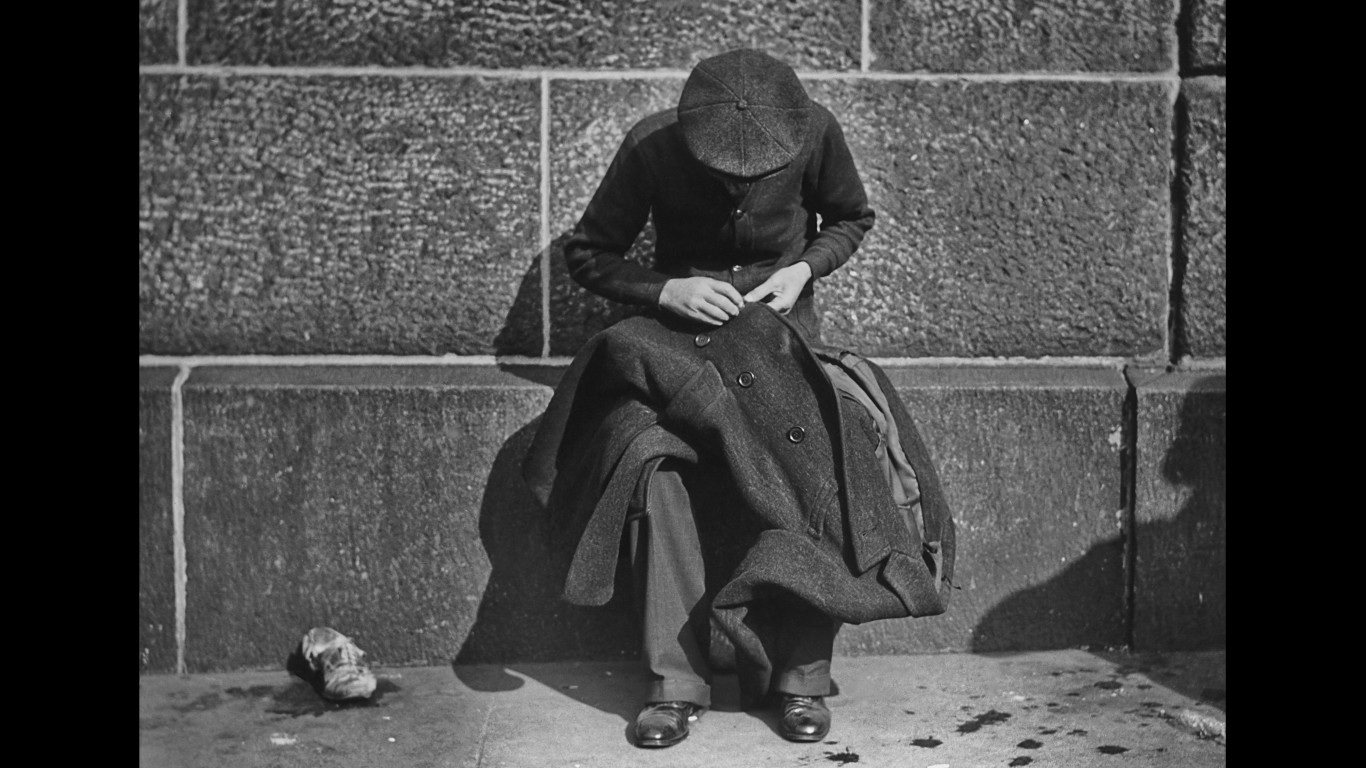

Making repairs (1935)

A homeless man fixes his overcoat, which he hopes to barter, possibly for food. Meeting places where the homeless barter goods were not uncommon during the Great Depression.

Homes for the homeless (1935)

Unemployed people live in huts made of salvaged materials in Greenwich Village, some decorated with pictures to make them more like home. The image was taken by Berenice Abbott, one of the most famous American photographers of the 20th century.

[in-text-ad]

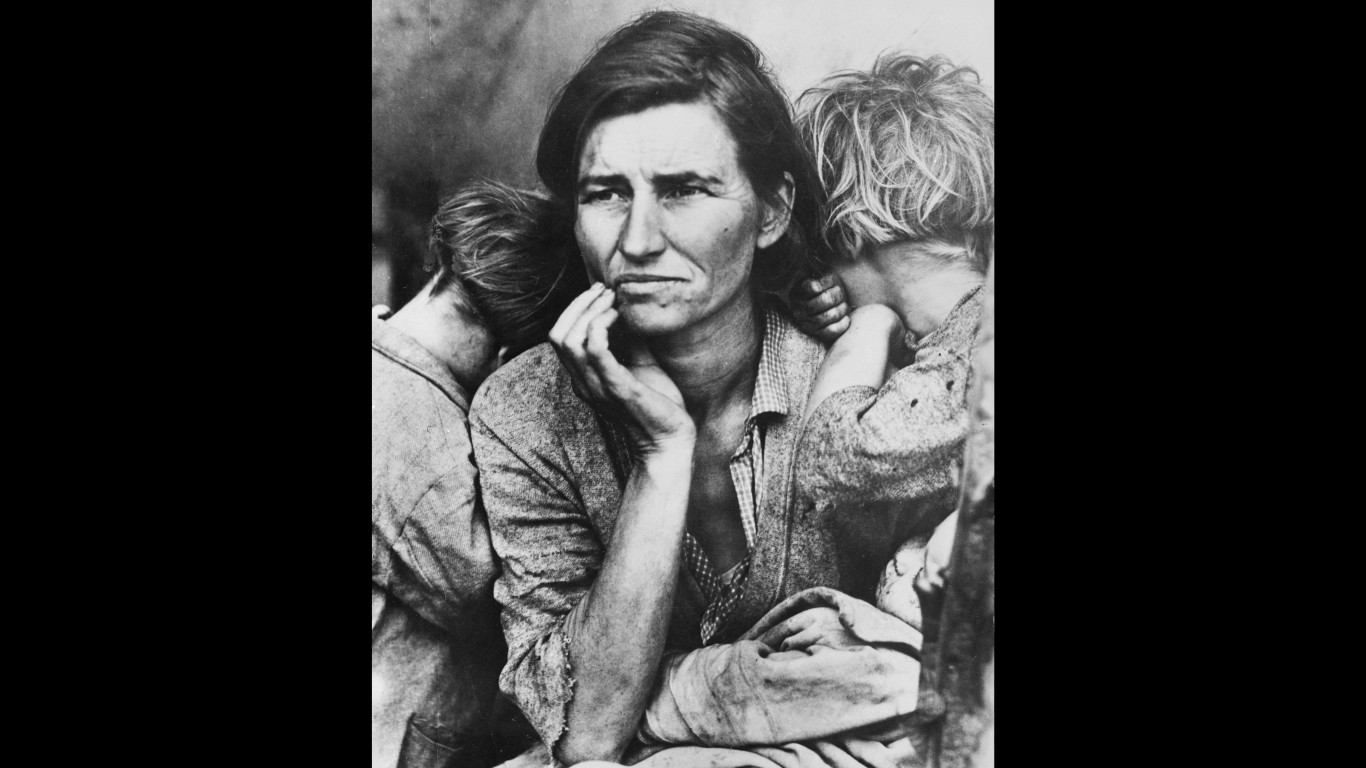

A mother’s despair (1936)

The legendary Dorothea Lange took this image of migrant mother Florence Thompson holding her baby and flanked by two of her seven children at a farm workers’ camp in Nipomo, California – not only one of the most famous photos symbolizing the grinding poverty of the Great Depression but also one of the most famous pictures ever taken.

Getting some relief (1936)

Unemployed men in Imperial Valley, California waiting to collect their relief checks. President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized about $5 million in work-relief programs when he signed the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act in 1935, still the largest system of public-assistance relief programs in U.S. history.

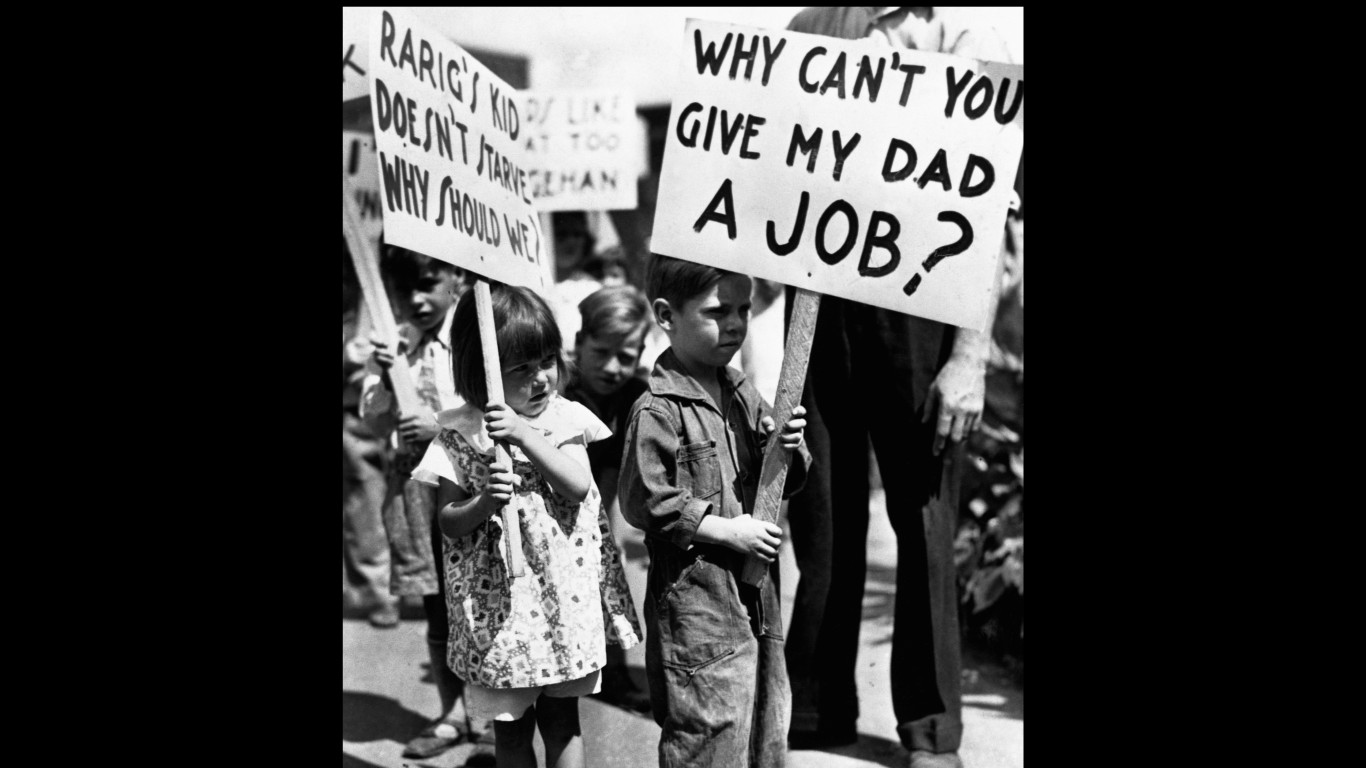

Children on the picket line (1937)

Children in Minnesota carry picket signs at a demonstration for the Workers Alliance of America – a short-lived organization that tried to unionize and represent people working on projects for the Works Progress Administration, another New Deal program.

[in-text-ad-2]

A man and his mules (1938)

A client of the Farm Security Administration – a New Deal agency that aimed to help poor farmers, sharecroppers, and migrant workers – near Morganza, Louisiana.

Bank failure (1939)

Representatives of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) post a notice announcing that the New Jersey Title Guarantee and Trust Company in Jersey City has failed. The notice reassures investors that they will lose very little money, because all deposits up to $5,000 are protected.

[in-text-ad]

Under the bridge (1940)

The Great Depression is considered to have ended in 1939, but its effects lingered on, as seen by these squatter shacks under the D Street Bridge in Marysville, California, early in 1940.

Are you ahead, or behind on retirement? For families with more than $500,000 saved for retirement, finding a financial advisor who puts your interest first can be the difference, and today it’s easier than ever. SmartAsset’s free tool matches you with up to three fiduciary financial advisors who serve your area in minutes. Each advisor has been carefully vetted and must act in your best interests. Start your search now.

If you’ve saved and built a substantial nest egg for you and your family, don’t delay; get started right here and help your retirement dreams become a retirement reality.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.