What makes a great military leader? According to retired Army Maj. Gen. John L. Gronski, senior mentor for the U.S. Army Mission Command Training Program, there are four basic qualities:

“Attitude, work ethic, relationship building, and character are essential for military leaders to possess whether they be commissioned officers, warrant officers, or non-commissioned officers,” Gronski wrote in Reserve + National Guard magazine in 2021. “Leading is a people business.”

A good way to examine how these qualities interact is by examining the lives of the most famous U.S. generals of World War II. All of these men had incredible work ethic and self-discipline, were adept at creating effective relationships with others, and were packed with attitude and character that inspired others around them to meet their high expectations.

24/7 Tempo compiled its list of America’s most famous World War II generals by drawing on information from sources such as Britannica and United States Army Military History Center. Many of the generals on our list number among the greatest generals in American history.

Out of the 20 most renowned American World War II generals, two earned the Medal of Honor, the highest U.S. military decoration, and seven were pinned with the Purple Heart, the award for being wounded in battle. One of these was a Brooklyn-born orphan drawn to military service by books he read in school about the Civil War.

Then there’s Gen. Claire Lee Chennault of Commerce, Texas, who repeatedly failed to get into flight school but would hit the books hard to earn his wings and went on to pioneer air-combat tactics, and Gen. Carl Spaatz of Boyerstown, Pennsylvania, who dutifully commanded operations that dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki despite his opposition to the use of nuclear weapons. (Here are 26 cities that were destroyed by war.)

There’s Gen. Lucian Truscott, an Oklahoma-raised former high school principal who shared the same soldier-inspiring swagger and grit as the man in whose shadow he lived, Gen. George S. Patton, and there’s the surly Gen. Joseph Stillwell of Palatka, Florida, a polyglot who spoke fluent Mandarin and commanded the unofficial “third theater” of the war in China-Burma-India.

Despite their different backgrounds and key competencies, all of these men shared qualities of great leadership that work on and off the battlefield.

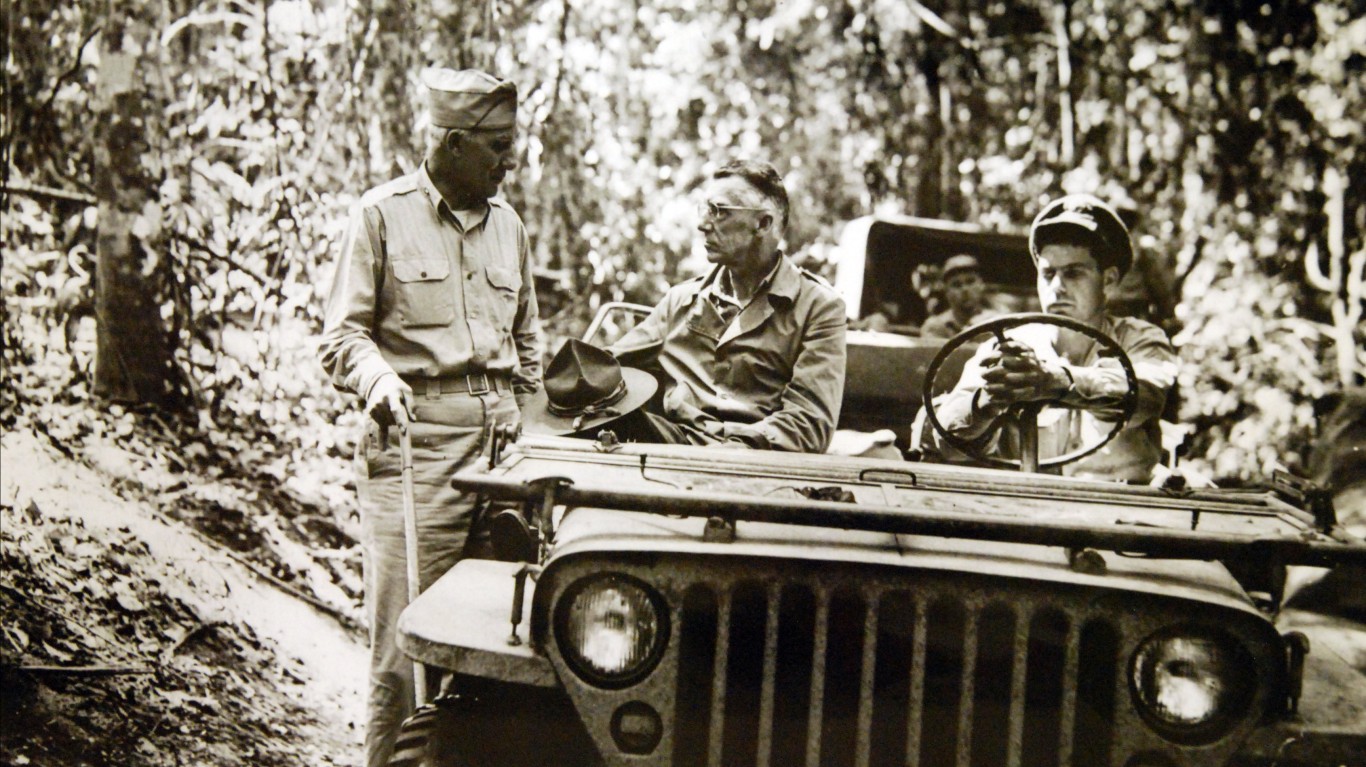

Alexander McCarrell Patch (1889-1945)

> Medals and/or stars: Army Distinguished Service Medal, Navy Distinguished Service Medal, Bronze Star/Lieutenant General/Three Stars

Patch was among the first American soldiers to be trained in machine gunnery and was instrumental in developing combat mechanization. He was also one of the few U.S. commanders to fight in both the Pacific and Europe: He directed troops at Guadalcanal and later commanded the Seventh Army’s invasion of southern France, an operation known as the “Second D-Day,” as it took place weeks after the Invasion of Normandy. Patch died at 55, weeks after the end of the war, from lung complications linked to influenza that he had contracted during the 1918 Pandemic. He was posthumously promoted to general in 1954.

[in-text-ad]

Carl Spaatz (1891-1974)

> Medals and/or stars: Distinguished Service Cross, Army Distinguished Service Medal, Bronze Star/General/Four Stars

Born in Boyertown, Pennsylvania, Spaatz is perhaps best known as the American commander who oversaw strategic bombing of Japanese cities. Though he opposed the use of nuclear weapons, he also directed the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Spaatz served as a combat pilot in World War I and became the first chief of staff of the newly independent U.S. Air Force after World War II. Spaatz oversaw air assaults in North Africa and Italy, and by January 1944 was commanding the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, where he orchestrated bombings against Germany’s aircraft and fuel factories.

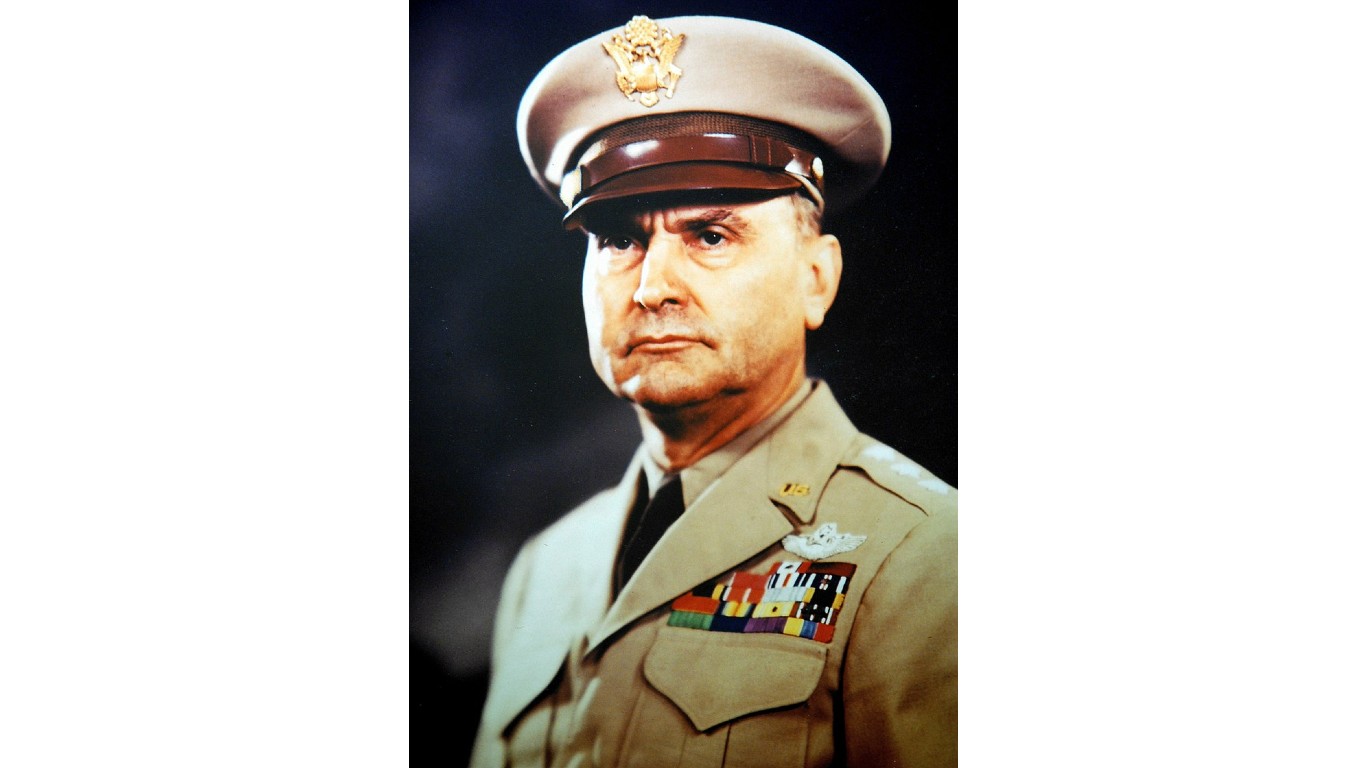

Claire Lee Chennault (1890-1958)

> Medals and/or stars: Army Distinguished Service Medal, Distinguished Flying Cross/Lieutenant General/Three Stars

After enlisting for World War I and enduring repeated rejections for flight training, Chennault finally earned his wings while stationed in San Antonio. He retired from the military in 1937 for health reasons, but traveled to China where he became advisor to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and later recruited volunteer U.S. pilots to create the American Volunteer Group (AVG), a.k.a. the Flying Tigers – named after their P-40B fighters decorated with tiger shark’s teeth and eyes painted on their noses. The AVG and the British RAF were instrumental in checking Japan’s westward march through Burma and Rangoon. Chennault, who became a major activist against the spread of Communism in the Far East after the war, died in New Orleans shortly after Congress awarded him the honorary rank of lieutenant general.

Douglas MacArthur (1880-1964)

> Medals and/or stars: Medal of Honor, the French Légion d’honneur and Croix de guerre, the Order of the Crown of Italy/General of the Army/Five Stars

Douglas MacArthur followed in the steps of his father, Arthur MacArthur Jr., a highly decorated lieutenant-general who participated in every U.S. war from the Civil War to the Philippine-American War. Douglas first met George S. Patton during World War I, a man with whom he shared a sense of self-aggrandizing fearlessness, emboldened by their successes in commanding forces during World War II – Patton directing tanks in Europe and Macarthur jumping his soldiers from island to island in the Pacific. MacArthur is one of two generals on this list to earn the Medal of Honor, the highest U.S. military decoration.

[in-text-ad-2]

Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969)

> Medals and/or stars: Army Distinguished Service Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, National Defense Service Medal/General of the Army/Five Stars

Eisenhower began his military career as a newbie second lieutenant in 1915 who so desperately wanted to see action that he was reprimanded for repeatedly applying to be deployed to Europe during the World War I. His commanding officers had other plans for him: running Camp Colt in Pennsylvania, the first U.S. tank-training camp. When America entered World War II, Eisenhower was assigned the task of war planning, including the Allied invasion of Europe. Eisenhower’s military success came after years of obscurity and lack of battlefield experience, owing largely to his organizational and strategy skills, and ability to instill optimism and confidence among his colleagues and subordinates – characteristics that, along with his war-hero status, would later help him become the 34th president of the United States.

George C. Marshall (1880-1959)

> Medals and/or stars: Army Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star, Croix de Guerre/General of the Army/Five Stars

Marshall, one of the five generals on this list to earn five stars, began his career out of the Virginia Military Institute as a second lieutenant in the 30th Infantry Regiment in the Philippines. Later, as assistant chief of staff of the 1st Infantry Division during World War I, he won recognition for his planning of the Battle of Cantigny. By World War II, Marshall was chief of staff, organizing the biggest military expansion in US history. He directed U.S. war operations from 1941 to 1945 and was named secretary of state after the war. The Marshall Plan, the massive US foreign aid package to help Europe rebuild after the war, is named after him.

[in-text-ad]

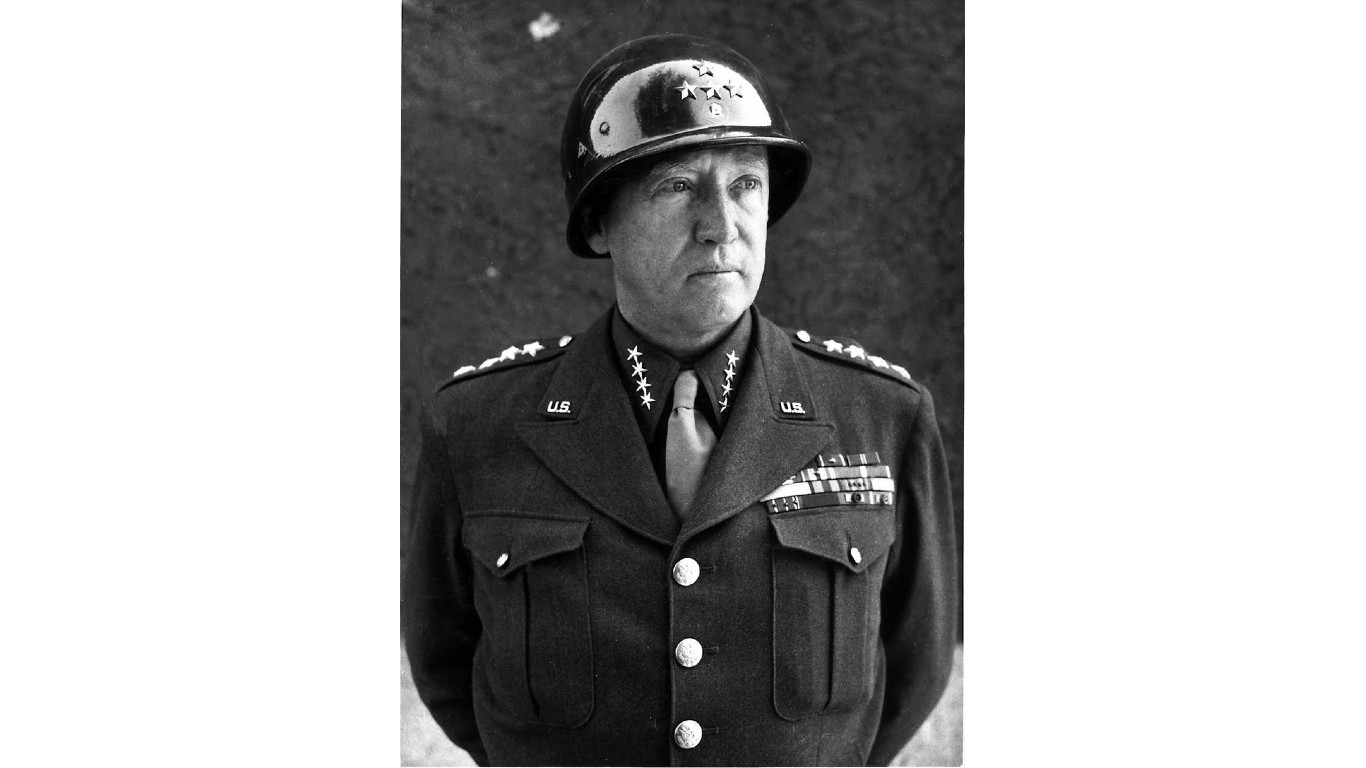

George S. Patton (1885-1945)

> Medals and/or stars: Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart/General/Four Stars

Nicknamed “Old Blood and Guts,” Patton was one of the toughest generals of World War II and one of only of six generals on this list to earn a Purple Heart – in his case for being shot through the leg while leading a tank and six men in an attack on German machine gunners during the World War I. He started his rough-and-tumble military career fighting men loyal to Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa before becoming the first officer in the new U.S. Army Tank Corps. Patton’s career highlights included leading the Seventh Army in the invasion of Sicily in 1943, marching across northern France with the Third Army the following year, and playing a part in routing the Germans at the Battle of the Bulge. Patton died from injuries incurred in a car crash in Germany in December 1945.

Henry “Hap” Arnold (1886-1950)

> Medals and/or stars: Army Distinguished Service Medal, Distinguished Flying Cross/General of the Army/Five Stars

Arnold graduated from West Point in 1907 and four years later was given flight training by the Wright Brothers. In 1912, he established a new altitude record by piloting a glider-like Burgess-Wright plane to 6,540 feet. As one of the first military aviators, Arnold’s achievements centered around his role in major developments of U.S. air power, notably the development of the B-17 Flying Fortress and the B-24 Liberator. By the time America got involved in World War II, Arnold was heading the Army Air Corps and earned his fifth star. After the war, he became General of the Air Force, making him the only five-star general to hold that rank in two separate armed services.

Ira Clarence Eaker (1896-1987)

> Medals and/or stars: Air Force Distinguished Service Medal, Army Distinguished Service Medal, Navy Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star,Lieutenant General/Three Stars

After serving in the Philippines, Eaker returned stateside in 1924 to take a high-ranking position in the Office of Air Service in Washington D.C., and in 1927 he was a pilot of the Pan American Flight goodwill mission in South Americas. (Another general on this list, Henry “Hap” Arnold, was instrumental in the creation of Pan American Airways, aimed at stopping the growing influence of a German-owned airline operating in South America.) Soon After the U.S. became involved in World War II, Eaker became commanding general of all American Army Air Forces in the U.K. Toward the end of the war, Eaker was commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces. He earned his fourth star nearly 40 years after he retired for his contributions to U.S. aviation and national security.

[in-text-ad-2]

James Harold Doolittle (1896-1993)

> Medals and/or stars: Medal of Honor, Army Distinguished Service Medal, Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star/Lieutenant General/Three Stars

Doolittle, an aviator who led a major air raid over Japan four months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, is the only other general on this list besides Douglas MacArthur to earn the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military decoration. He’s also one of the few U.S. generals to have aircraft testing and racing talents. He resigned from the Army Air Corps in 1930, but while working in the aviation department of Shell Oil Company, Doolittle heard the call to return to service with the outbreak of World War II. He famously led a fleet bombers over Tokyo, Yokohama, and other major Japanese cities, before landing in China. Though that bombing run did little damage, it boosted American morale and forced the Japanese to devote resources to bolstering air defenses.

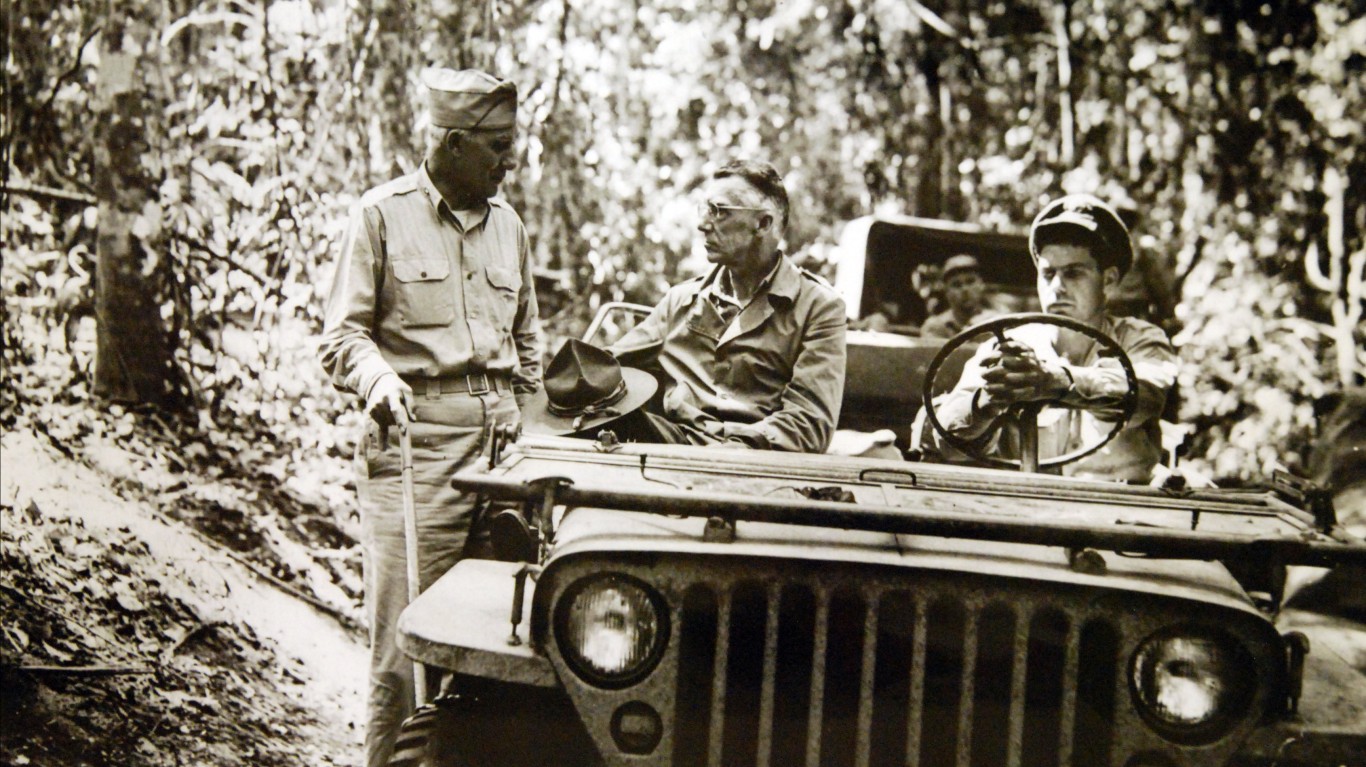

James Lawton Collins (1882-1963)

> Medals and/or stars: Army Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star/General/Four Stars

Collins was one of the senior U.S. military officials to serve in both the Pacific and European theaters of war. By the time the country entered World War II, the New Orleans native was a temporary Army colonel who rose quickly in the ranks to serve as the youngest division commander in the army when he was appointed to lead the 25th Infantry Division. He once again broke an age record when a year later he was named commander of the VII Corps in the Allied invasion of Normandy. Later, he wrote of his adversaries that while the Germans were more professional and skilled in mechanized warfare, “the Germans didn’t have the tenacity of the Japanese.”

[in-text-ad]

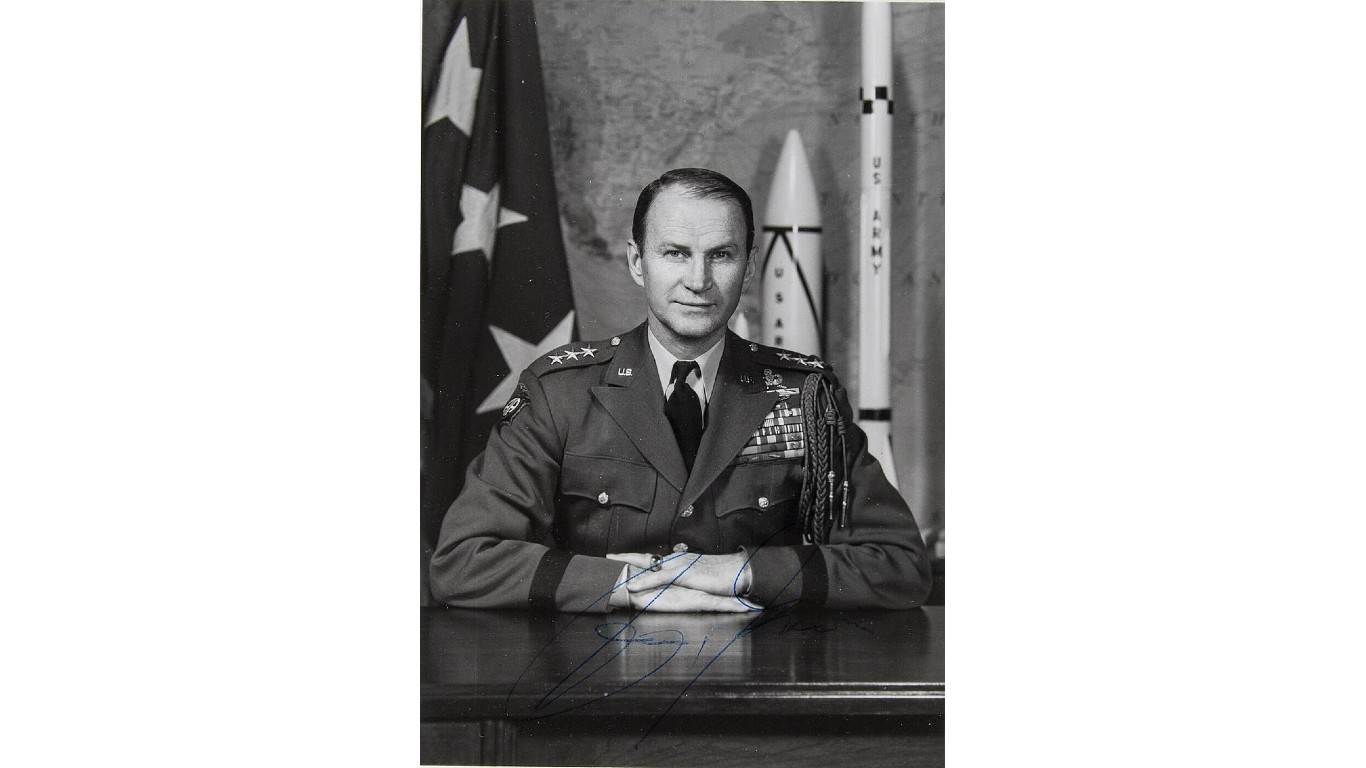

James Maurice Gavin (1907-1990)

> Medals and/or stars: Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart/Major General/Two Stars

Gavin is one of only two famous World War II generals born after 1900 – and the only orphan. He was inspired to armed service by books he read about the Civil War in elementary school under the care of adoptive parents. In 1924, Gavin took a train to New York City and enlisted at 17 and later made his way to West Point. As an adult, Gavin would become a major promoter and innovator in boosting the effectiveness of airborne troops. Gavin is also credited with integrating soldiers of the all-Black 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion into the 82nd Airborne Division shortly after the war.

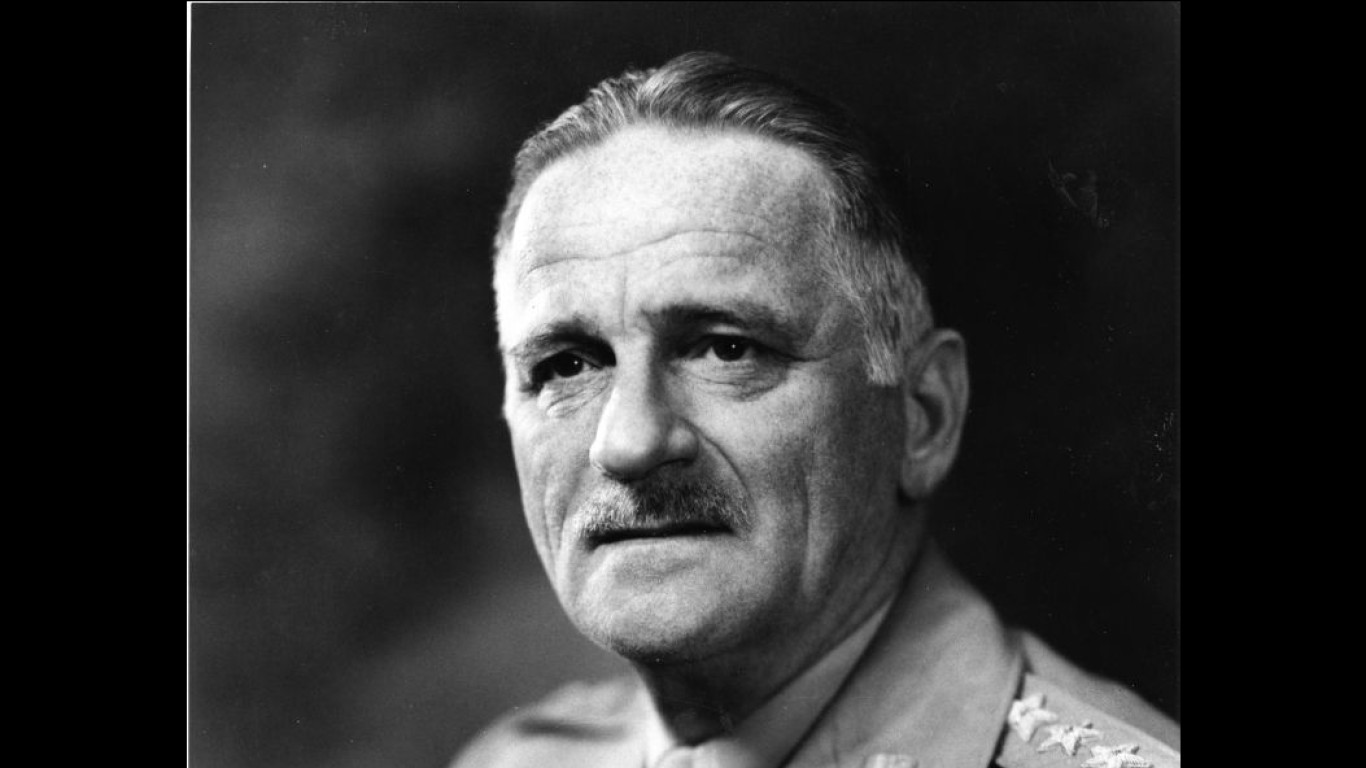

Joseph Stillwell (1883-1946)

> Medals and/or stars: Distinguished Service Cross, Army Distinguished Service Medal, Bronze Star/General/Four Stars

While Gen. Patton was known for his swagger, Gen. Stillwell’s main personality trait was his surliness; he earned the nickname “Vinegar Joe” by a student when Stilwell taught at the Infantry School at Fort Benning in Georgia. He was also known to dish out his own unflattering nicknames, calling Franklin D. Roosevelt “Rubber Legs,” mocking the president’s disability. But what he lacked in personability he made up with his skills. During World War II he became Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s chief of staff (Stillwell was fluent in Mandarin) and was commander of the Allies unofficial “third theater” in China-Burma-India, putting him at the same level of command as Gen. MacArthur in the Pacific and Gen. Eisenhower in Europe.

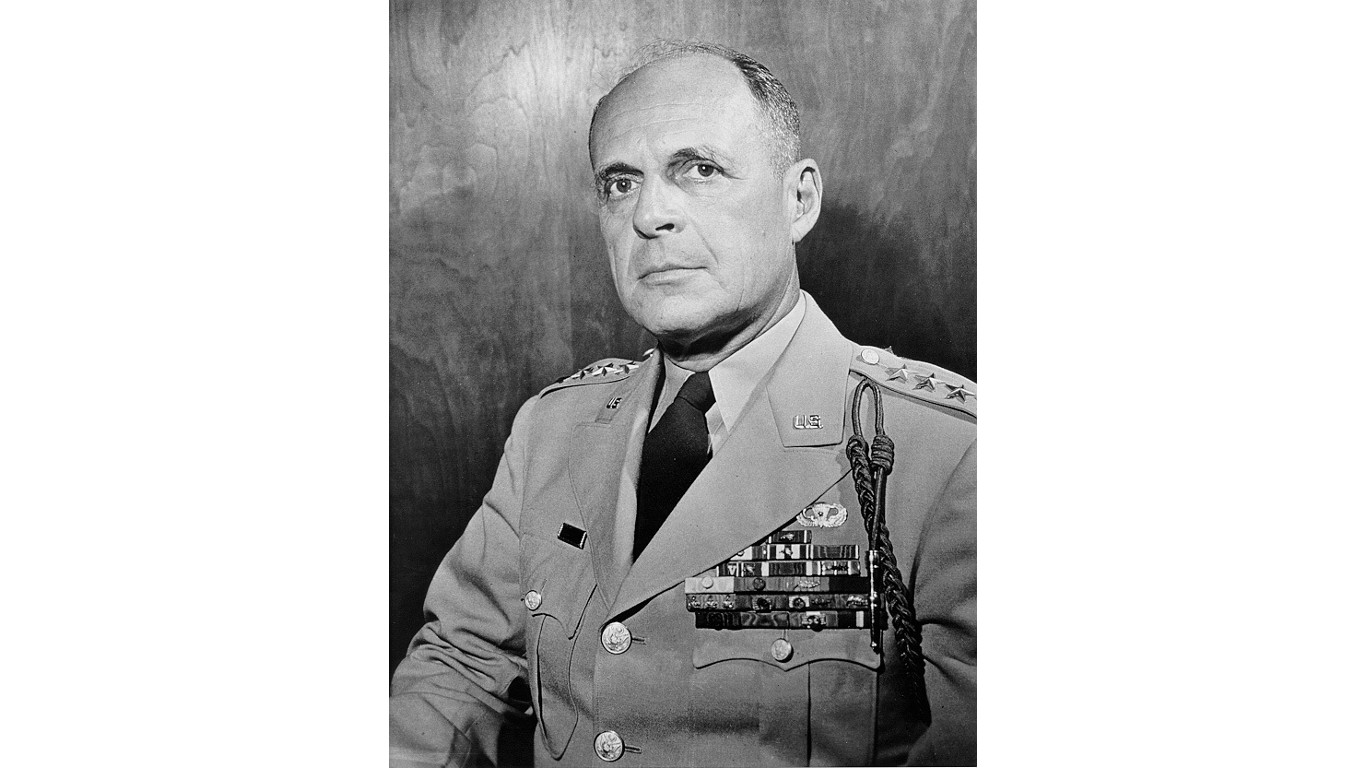

Lucian Truscott (1895-1965)

> Medals and/or stars: Distinguished Service Cross, Army Distinguished Service Medal, Navy Distinguished Service Medal, Purple Heart/General/Four Stars

Some World War II generals were made in the map rooms, delegating tasks and organizing campaigns within enormous organizational structures. Others were created on the battlefield. Truscott fit squarely in the latter category, with the requisite tenacity, courage, and tactical competence to lead soldiers into battle, notably on the beachheads and hills of Sicily and the Italian coast. Eisenhower rated Truscott second only to Patton as the war’s most able army commander. Indeed, both men were very similar, exhibiting their best under enemy gunfire and unafraid to challenge their superiors, with battle wins to back up their fractious personalities.

[in-text-ad-2]

Mark W. Clark (1896-1984)

> Medals and/or stars: Distinguished Service Cross, Bronze Star, Purple HeartGeneral/Four Stars

Fresh out of West Point, Clark fought in France during World War I where he was injured and earned a Purple Heart. During World War II, he was Gen. Eisenhower’s deputy during the U.S. invasion of French North Africa in November 1942 and was later commissioned to train the Fifth Army for the invasion of Italy in late 1943. He was also credited with driving the Germans out of Rome. He expressed an extreme aversion to the Soviets while commanding troops in Austria and protested what he called his country’s “cream puff and feather duster approach to communism.” He spent the rest of his life an outspoken anti-communist, echoing Joseph McCarthy’s views of a communist threat from within the United States.

Matthew B. Ridgway (1895-1993)

> Medals and/or stars: Distinguished Service Cross, Army Distinguished Service Medal,, Bronze Star, Purple Heart/Army Chief of Staff/Four Stars

Credited with converting the 82nd Infantry Division into the 82nd Airborne in 1942 and then using it to conduct the airborne component of the Sicily campaign, the first major airborne assault in US military history, Ridgway was a deft planner and strategist who also participated in significant combat missions. He parachuted into France with his troops during the Normandy Invasion, a hazardous but crucial mission that scattered U.S. soldiers across the Nazi-occupied interior of northern France. Afterwards, he led the XVIII Airborne Corps across the Netherlands, Belgium, and into Germany. After the war, Ridgway commanded the Eighth Army in the Korean War, succeeded Gen. Douglas MacArthur as Allied commander in the Far East, and oversaw the withdrawal of American troops from Japan in 1952.

[in-text-ad]

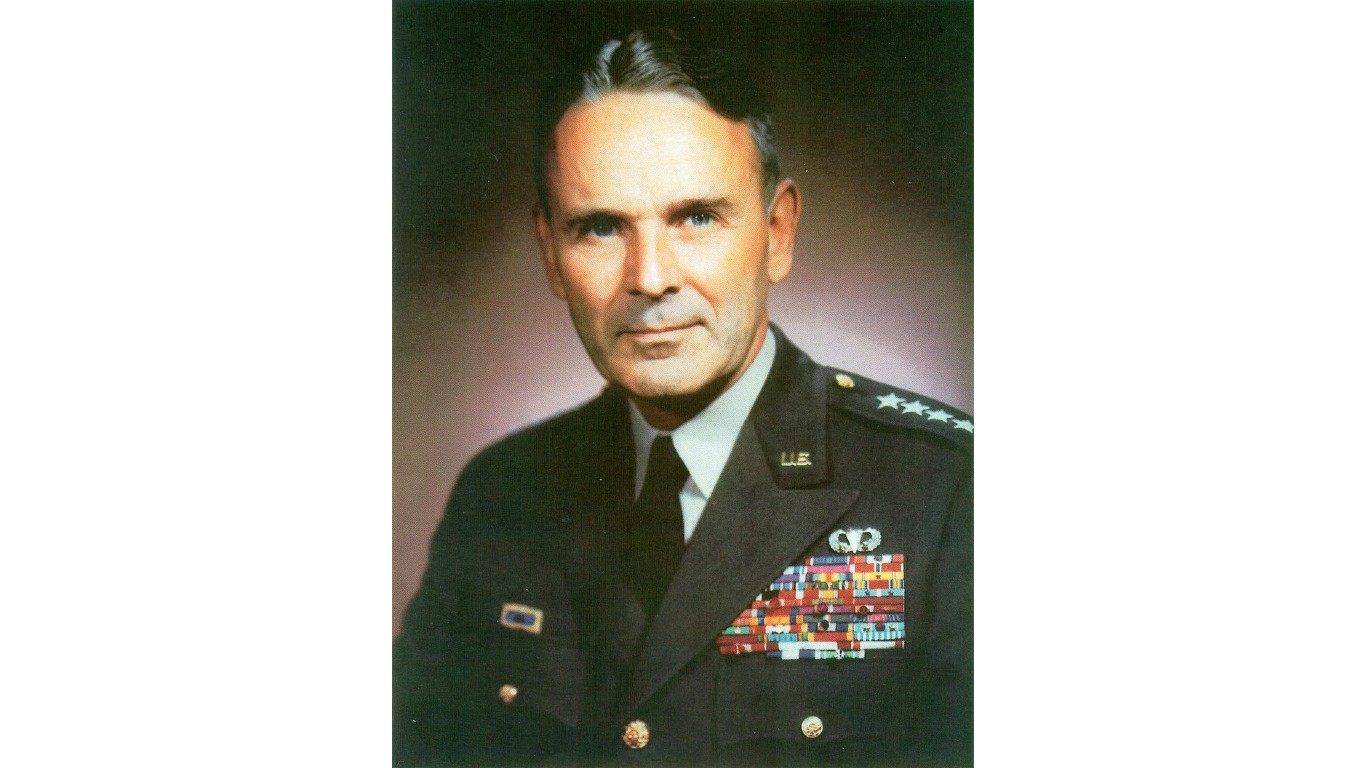

Maxwell D. Taylor (1901-1987)

> Medals and/or stars: Distinguished Service Cross, Army Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star, Purple Heart/General/Four Stars

Taylor is credited with assisting Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway in creating the 82nd Airborne Division early in World War II, and subsequently commanded artillery during the Sicilian and Italian campaigns. Hours before the Allied invasion of Italy, Taylor took an incredible risk by secretly crossing enemy lines to meet with pro-Allied Italian leaders regarding a planned air assault on Rome. He also parachuted with his troops of the 101st Airborne Division during the invasion of Normandy. He led the division in the failed Battle of Arnhem in the Netherlands in September 1944, but he rebounded with a successful defense of Bastogne in Belgium during the Battle of the Bulge later that year.

Omar Bradley (1893-1981)

> Medals and/or stars: Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart/General of the Army/Five Stars

If the name Bradley sounds familiar, it should. The Bradley series of tracked armored fighting vehicles, used to transport troops and scouts while providing suppressing fire, is named after him. In 1943, Bradley became Gen. Eisenhower’s representative during the North African campaign where he commanded the troops that smashed through German lines in Tunisia to seize the port city of Bizerte. After winning promotion to lieutenant general, Bradley led troops in the invasion of Sicily and later led the First Army in the Normandy invasion. Under his command, his troops moved quickly through German-occupied France. In August 1944, Bradley was assigned command of the 12th army, which would later be consolidated with other Army groups to become the largest body of U.S. fighters ever to serve under one commander.

Walter Bedell Smith (1895-1961)

> Medals and/or stars: Army Distinguished Service Medal, Bronze Star/Major General/Two Stars

Like a number of other famous American World War II generals, Smith cut his teeth on the battlefields of France during World War I. Also like some others on this list, he spent time in between the wars working to modernize U.S. military capabilities, as the American armed forces had only recently become mechanized with greater participation of aircraft. Early on, Smith captured the attention of Gens. Bradley and Marshall and became colonel months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Smith was an administrative general, spending most of World War II as Gen. Eisenhower’s chief of staff, often representing him at Allied high-command conferences.

[in-text-ad-2]

Walton Walker (1889-1950)

> Medals and/or stars: Distinguished Service Cross, Army Distinguished Service Medal, Distinguished Flying Cross, Silver Star, Bronze Star/Lieutenant General/Three Stars

After participating in the occupation of Veracruz, Mexico, in 1914, and serving in World War I as a machine gunner in France, Walker spent the period between the great wars as a military instructor in Oklahoma and Georgia and at West Point before graduating from the Army War College in 1936. After the U.S. entered World War II, Smith was given command of an infantry division, then an armored division, then a larger armored corps to prepare units for the campaign in North Africa. Smith’s XX Corps would later become part of Gen. Patton’s Third Army, earning the nickname “Ghost Corps” for how quickly they broke through Germany’s Siegfried Line of defense.

Credit Card Companies Are Doing Something Nuts

Credit card companies are at war. The biggest issuers are handing out free rewards and benefits to win the best customers.

It’s possible to find cards paying unlimited 1.5%, 2%, and even more today. That’s free money for qualified borrowers, and the type of thing that would be crazy to pass up. Those rewards can add up to thousands of dollars every year in free money, and include other benefits as well.

We’ve assembled some of the best credit cards for users today. Don’t miss these offers because they won’t be this good forever.

Flywheel Publishing has partnered with CardRatings for our coverage of credit card products. Flywheel Publishing and CardRatings may receive a commission from card issuers.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St. 24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.