What was Earth like one million years ago? If our planet is 4.54 billion years old, a million years is not much more than an eyeblink in eternity. In human terms, however, what the world was like a million years ago is difficult to comprehend. Science has helped us understand the distant past by unlocking many of its mysteries and opened a window on what life must have been like on our planet around 1,000,000 BC.

To get a picture of what the world was like a million years ago, 24/7 Tempo has reviewed materials and information from sources such as such as the British Geological Survey, NASA, and tapped the expertise of university academics who specialize in geology and earth science.

If you had observed Earth from space a million years ago, the alignment of the continents would have looked very much like it does today. But upon closer inspection, the differences would become apparent. This was the Pleistocene Epoch, when Earth was colder and probably experiencing one of its ice ages, which were frequent. The amount of frozen water would have dropped the level of oceans. The lower sea level would have exposed land bridges between continents, allowing freer migration for our ancestors as well as animals and plants.

There were large lakes in the western part of the United States that are now gone, but the Great Lakes in middle America were not yet created. England, Shakespeare’s “sceptered isle,” was joined with the European continent.

Crocodiles, lizards, turtles, pythons, and other reptiles proliferated during this time, as did birds such as ducks, geese, hawks, and eagles. Larger versions of contemporary animals such as sloths, venomous lizards, marsupials, and armadillos roamed the landscape, before they were doomed by natural selection. Our ancestors also might have played a role in their demise by hunting them. Modern-day humans are disrupting the habitats of creatures all over the world through overbuilding, poaching, and generating pollution. Here are animals humans are driving to extinction.

Because of glacial activity, water and vegetation was scarce. There were some conifer trees like pine and cypress, and deciduous trees such as oak and beech.

As for our human ancestors, they were evolving into what would become modern humankind. They were crafting tools and employing fire. And they were doing their best not to become a meal for the ravenous mammals such as saber-toothed tigers and cave lions. It would take a while before humans would dominate the planet. Here are the other deadliest mammals in the world.

Methodology

To help determine what the world was like a million years ago, 24/7 Tempo reviewed sources such as livescience.com, nasa.gov, universitytoday.com, space.com; insidescience.org; media sites such as pbs.org; and consulted experts including Ron Blakey, geology professor emeritus at North Arizona University, and Gail Ashley, professor emerita, at the Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences at Rutgers University.

Earth was colder

In geologic terms, a million years ago was the Pleistocene age (2.5 million years BC to 11,711 years BC), and Earth was five to 10 degrees colder than it is today. Prolonged glaciation periods occurred during this time,

[in-text-ad]

Lower sea levels

The sea levels were much lower. Geologists estimate that difference in sea level between glacial epochs was as much as almost 400 feet.

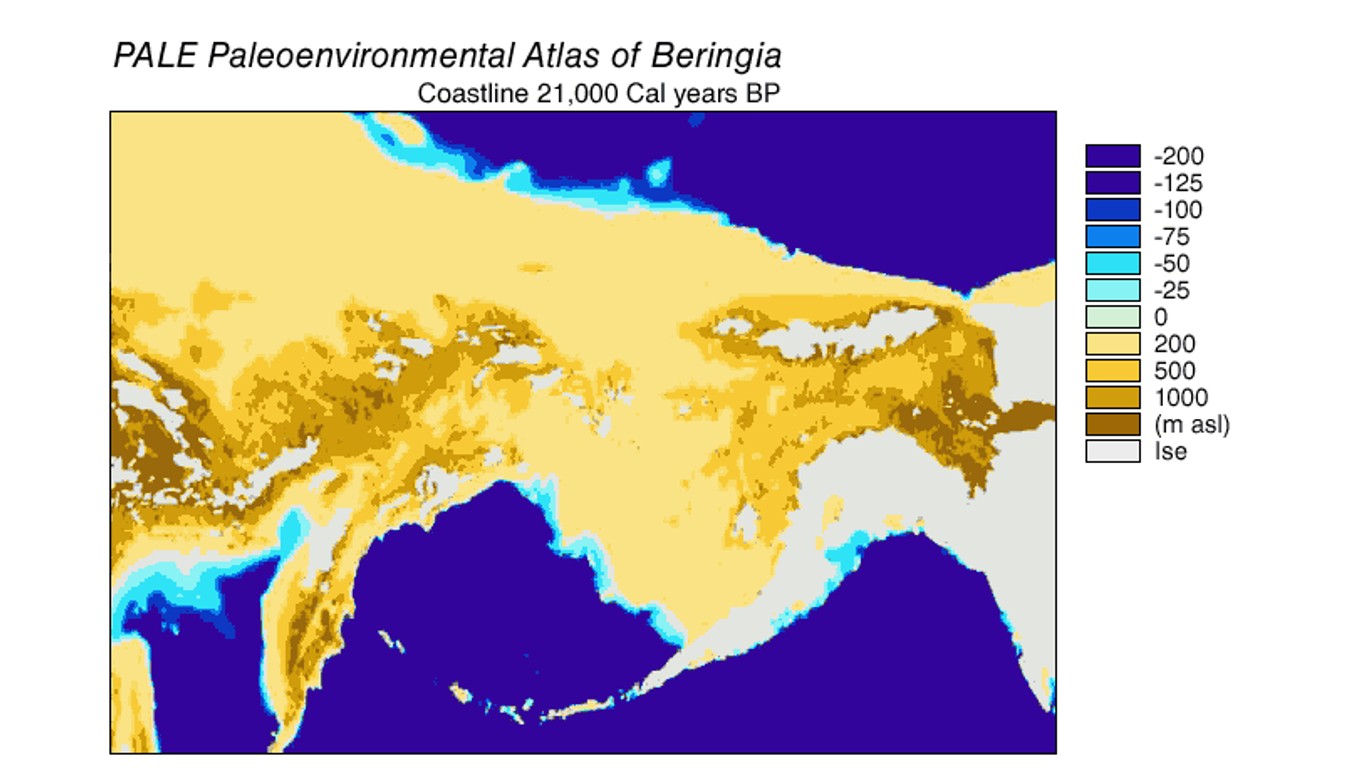

Bering Strait land bridge

Because of lowered sea levels, the narrow Bering Strait of today might have had a land bridge, allowing migration from Asia to North America. The idea of a land bridge has fascinated people for hundreds of years. The first written record that suggested the existence of such a bridge was recorded in 1590 by Spanish missionary Fray José de Acosta.

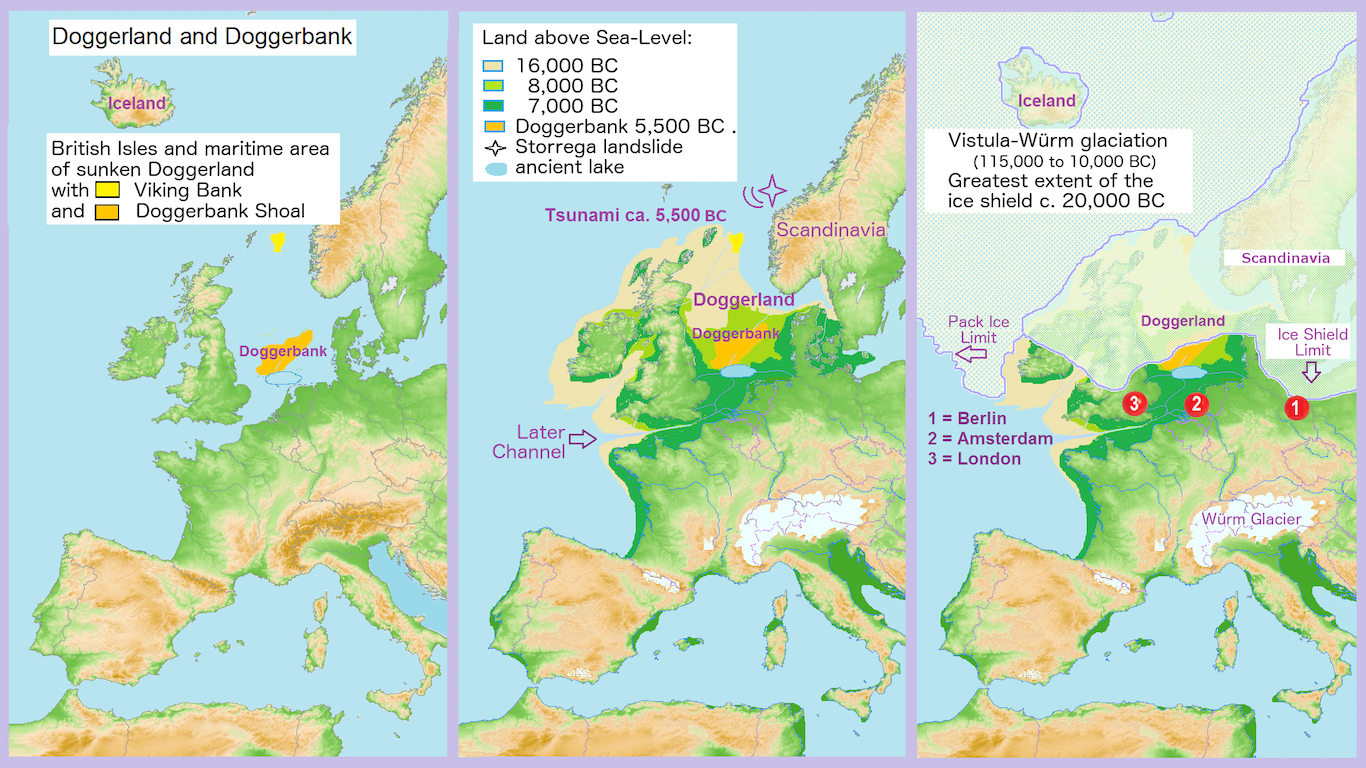

The British Isles were connected to Europe

There was once a land bridge between Britain and continental Europe before rising seas submerged it. The ice age lowered sea levels dramatically, exposing the sea bed. The area between much of the northern coast of Europe and Britain was called Doggerland and provided a route for animals to go to the warmer climes of southern Europe.

No Baltic Sea

There was no Baltic Sea a million years ago. The Baltic Sea is the youngest seas in the world, appearing between 10,000 and 15,000 years ago as the ice sheets from the ice age retreated.

Grand Canyon eruptions

Between 1.25 million BC and 250,000 BC, scientists believe there were 13 major volcanic eruption periods in the Grand Canyon.

Dust storms

Because the water levels were lower due to the Ice Age, the continents experienced dust storms.

No Great Lakes

The five Great Lakes — Superior, Huron, Michigan, Ontario, and Erie — form the largest interconnected body of fresh water on Earth, but they didn’t exist a million years ago because of the ice sheet that covered much of Canada and the northern United States.

Prehistoric lakes

One million years ago, there were large freshwater lakes in what is now the western United States — Bear Lake on the Utah-Idaho border; Utah Lake near what is now Provo, Utah; and Lake Bonneville, which eventually formed the Great Salt Lake, the biggest inland body of salt water in the Western Hemisphere

Florida’s size fluctuated

Throughout most of its history, Florida has been underwater. However, during periods of glaciation, the peninsula would have expanded. When the sea level was at its lowest, Florida’s western coastline was probably 100 miles farther out than where it is today.

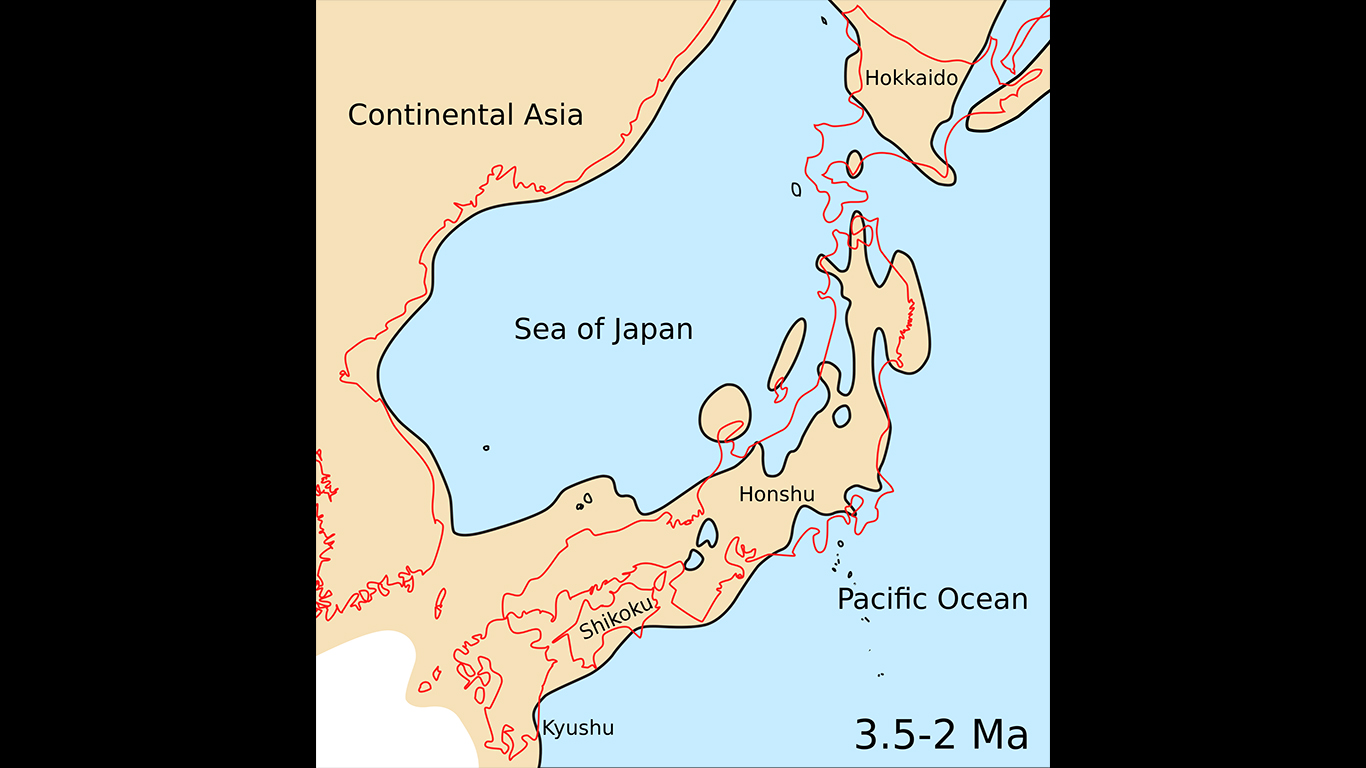

Japan connected to mainland where Korea is

Japan was once attached by land bridges to the Korean peninsula on the Asian mainland to the Korean peninsula. Some archaeologists think humans came to Japan via these land bridges 100,000 years ago.

Lake Malawi formed

Lake Malawi — which extends into parts of Malawi, Mozambique, and Tanzania — is one of the world’s oldest lakes, and with a surface area of 11,400 square miles, also one of the largest.

Tasmania and New Guinea were connected to Australia

Tasmania and New Guinea were linked with Australia because of lower sea levels from glaciation. After the ice retreated about 11,700 years ago, the sea levels rose, separating them into three distinct land masses.

Homo ancestor

By a million years ago, early hominids — our human ancestors — were walking upright and making tools. They were on the move. Our ancestors originated in Africa between one and two million years ago and eventually moved to Asia and Europe. Scientists speculate that climate change had a lot to do with their migration.

Gigantopithecus was the largest primate ever

Our ancestors had to share the earth with the biggest primate to ever trod the planet — Gigantopithecus, who was ten feet tall and tipped the scale at 1,100 pounds. Gigantopithecus died out 100,000 years ago.

20-foot-long sloths

Ground sloths that were a big as rhinos and elephants lived in North and South America. Some were as long as 20 feet and weighed up to four tons. The last of them passed on about 4,200 years ago.

Quinkana, a 23-foot-long crocodile in Australia

Quinkana, the predecessor of the crocodile that lives in Australia today, could grow to 23 feet long. Quinkana was a terrestrial crocodile, meaning it lived on land. Unlike today’s crocodiles, it did not drown its prey, but instead used its razor-sharp teeth to kill. Fossil records indicate it disappeared about 40,000 years ago, around the time the first humans arrived in Australia.

Megalania, 23-foot-long venomous lizards in Australia

Megalania were huge venomous lizards that inhabited Australia a million years ago. They are from the same lizard family as today’s Komodo dragon, but they’re bigger: Estimates place them at between 11 feet and 23 feet long. Like the Komodo dragons, Megalanias were fast, strong, and lethal. Victims such as pygmy elephants or tortoises would either die from their bite itself or from the poison from the bite. Megalanias disappeared around the time of human arrival in Australia 40,000 years ago.

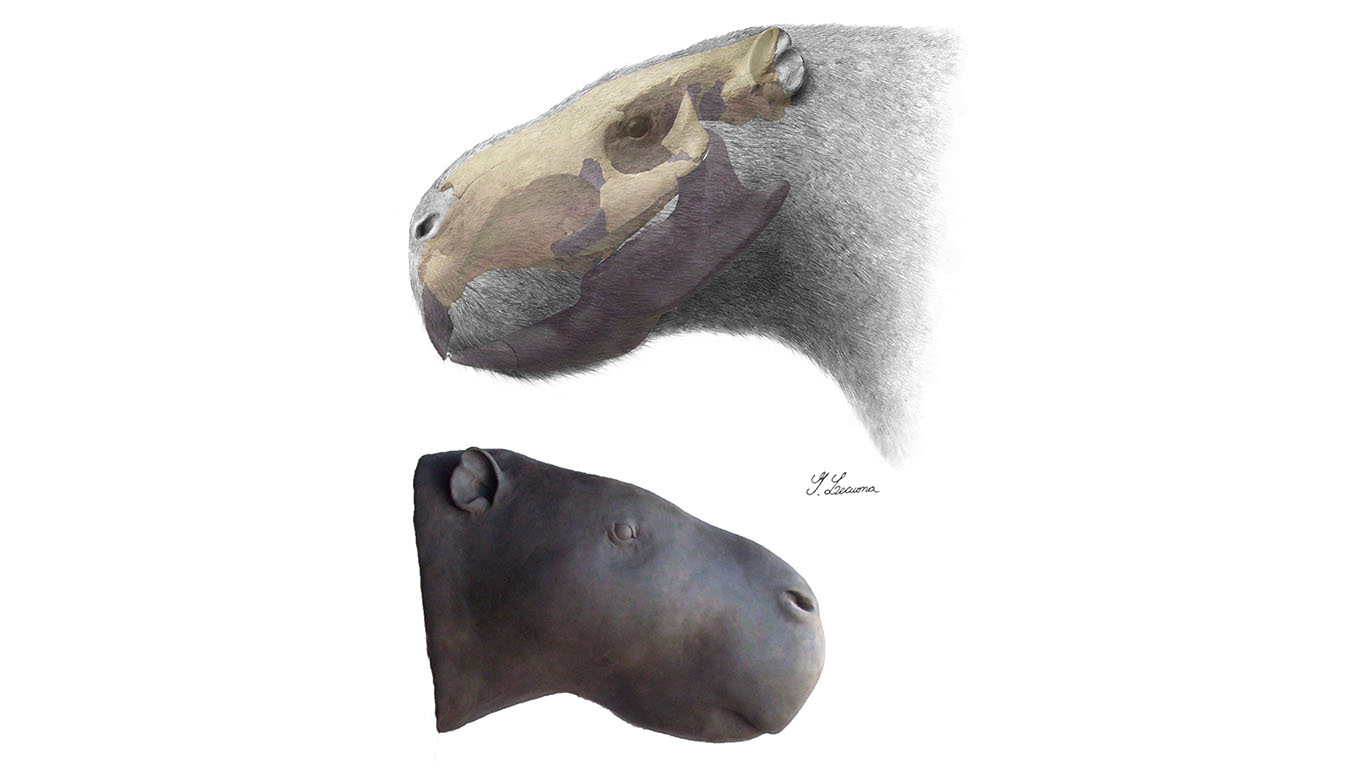

Giant marsupials in Australia

Giant marsupials stalked the Australian landscape from the late Oligocene (23 million to 33.9 years ago) to the Late Pleistocene period (which ended about 11,700 years ago). These beasts had large tapir-like heads and claws and weighed as much as 2,200 pounds. Scientists are not sure why these beasts grew so large. These Australian marsupials became extinct during the late Pleistocene epoch, perhaps because of climate change and interaction with humans.

Big armadillo-like animals in North America

The glyptodon was an armored, one-ton creature — nature’s tank — that was a larger version of today’s armadillo. It came to North America from South America over the Isthmus of Panama. An herbivore, it thrived in what is now coastal Texas and Florida before it became extinct about 8,000 years ago, probably because of overhunting by humans. Besides devouring the animals, early humans also used their armored shells for shelter.

Horses in North America

History tells us the first European settlers brought horses to the Americas. However, ancient wild horses had been in North America long before that, living here from roughly 50 million to 11,000 years ago. They became extinct at the end of the last Ice Age.

Aurochs, ancient cattle

Aurochs, ancestors of the modern cattle, roamed the Middle East and Europe. They came to Britain over the land bridge from the European continent 400,000 years ago. These animals could grow up to six feet tall at the shoulder and weighed as much as 6,000 pounds. The last of them survived into the 1600s.

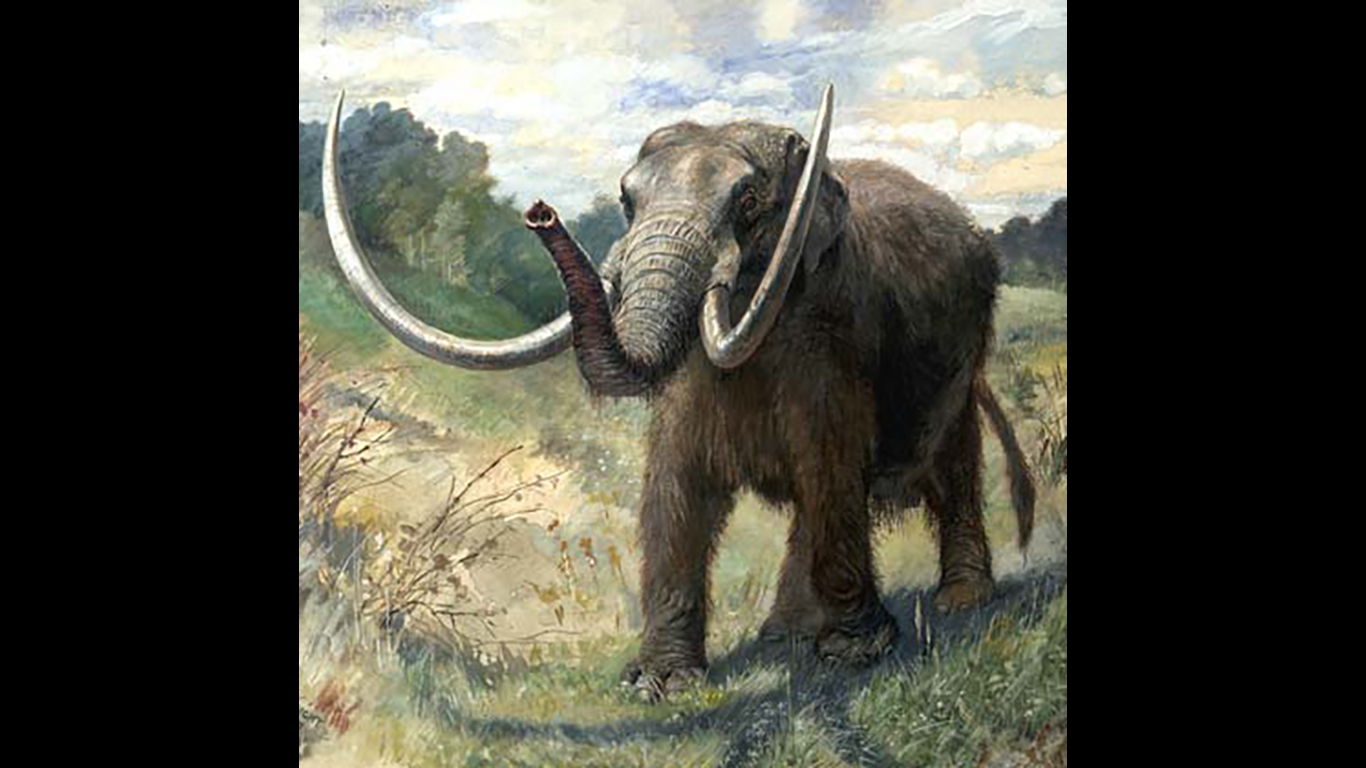

Mastodons

Mastodons, which looked like furry elephants but were shorter and stouter, came to North America about 15 million years ago, over the Bering Strait land bridge. They ranged from what is now Alaska down to today’s Honduras.

Straight-tusked elephants in Europe

Straight-tusked elephants inhabited earth’s landscape from Asia to what is now Great Britain. They were up to 13 feet tall and weighed as many as 13 tons. Unlike the furrier woolly mammoths, the elephants could not tolerate the cold and eventually migrated to warmer climates.

Woolly mammoths

Mammoths crossed the land bridge to North America between 1.7 million and 1.2 million years ago. Woolly mammoth’s tusks are long and more curved than those of their mastodon relatives. Another difference is in their teeth — mammoths had flat, ridged molars, allowing them to cut through vegetation, in contrast to the cusped teeth of the mastodon. Mammoths are more closely related to the present-day modern Asian elephant, and were about nine feet tall and weighed about six tons. Climate fluctuations and the increasingly sophisticated hunting methods of humans led to their demise.

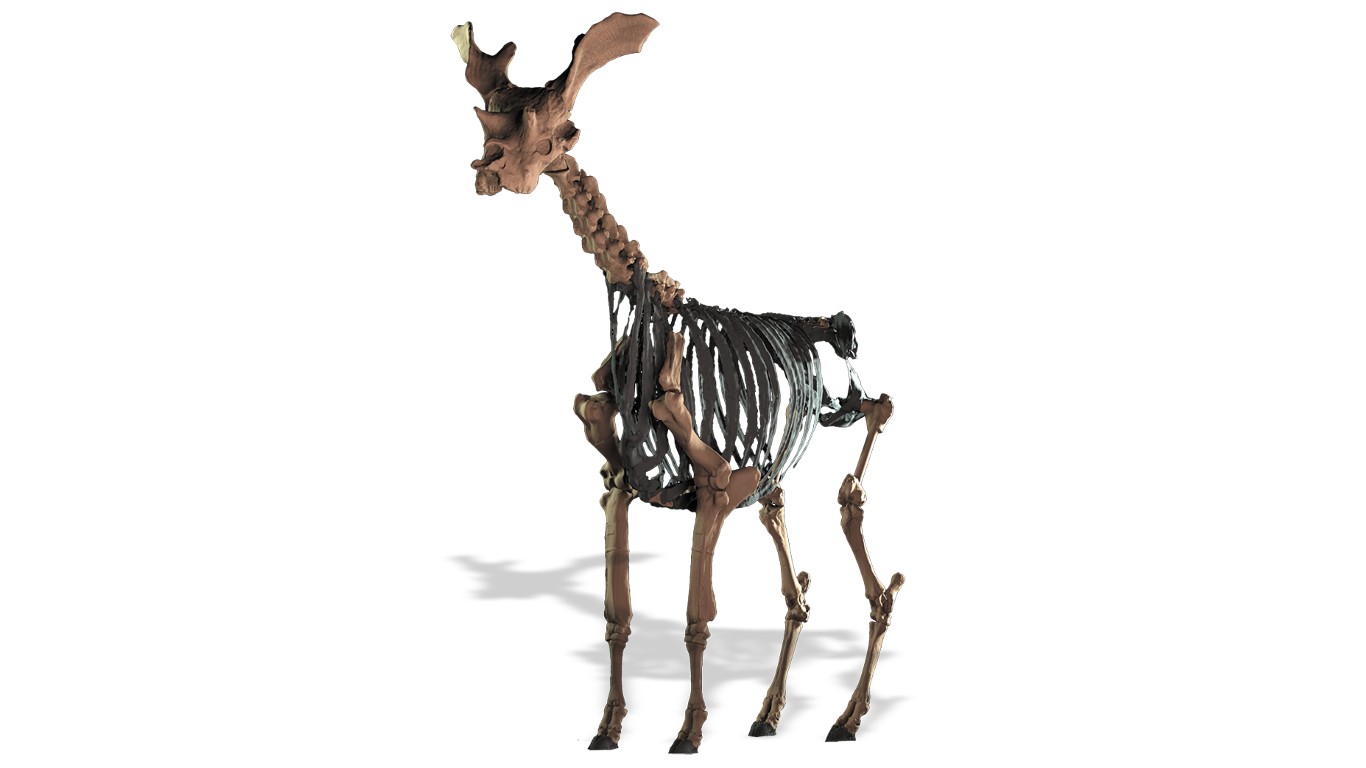

Sivatherium, giraffe predecessor in Africa

Sivatherium is an extinct girafid with small bumped horns that lived between five million and 10,000 years ago. The animal, related to today’s giraffe, was an herbivore that was 13 feet long and weighed about one ton. It consumed 50 to 100 pounds of grass a day. Sivatherium roamed from Africa to India. It was hunted to extinction by humans at the end of the last Ice Age.

Woolly rhinoceros in what is now Great Britain

The woolly rhinoceros, which were heavily muscled carnivores, could be found in what is now Great Britain. These animals had thick fur to protect them from the cold. Fossil evidence in the former land bridge between Great Britain and the Continent showed knife marks on the remains of woolly rhinos that suggests human ancestors hunted them.

Megantereon, saber-toothed cat in Africa

The megantereon, a sabre-toothed cat, was related to today’s lion, the latter of which would become an apex predator. Megantereon was about four feet long and lived in Africa, Europe, Asia, and North America. It disappeared about 500,000 years ago.

Wolf-like dog roamed South Africa

An ancestral version of the wild dog prowled ancient South Africa.The animal was about the size of a wolf. The oldest fossil remains of this animal are about a million years old. They were discovered in the 1990s at Gladysvale in South Africa, also called the Cradle of Humankind.

Cheetahs in North America

The American cheetah roamed present-day Texas between 3.2 million and 2.5 million years ago and went extinct about the time of the end of the last Ice Age. The animal had a shoulder height of just under three feet and weighed about 155 pounds. Although we think of cheetahs as very swift, this one probably wasn’t as fast its modern-day counterpart because its legs were shorter — but it was probably a good climber.

Giant beavers

Fossil records indicate that the giant beaver weighed up to 125 pounds, almost three times the size of today’s North American beaver. It inhabited the Great Lakes region, and migrated as far south as South Carolina.

[in-text-ad-2]

Camels

Ancestors of camels, or camelops, crossed the Bering Strait land bridge and lived in North America until 13,000 years ago. Fossil records indicate that they lived in North America during the Eocene period, about 45 million years ago. They lived in open spaces, though it is unclear if they could conserve water like today’s camels. Camelops stood about seven feet tall at the shoulder and weighed almost a ton.

Giant rodents in South America

A 1,500-pound rodent called Josephoartigasia monesi — the largest rodent ever — lived in South America starting about two million years ago. Its modern-day descendant is the guinea pig.

Take Charge of Your Retirement In Just A Few Minutes (Sponsor)

Retirement planning doesn’t have to feel overwhelming. The key is finding expert guidance—and SmartAsset’s simple quiz makes it easier than ever for you to connect with a vetted financial advisor.

Here’s how it works:

- Answer a Few Simple Questions. Tell us a bit about your goals and preferences—it only takes a few minutes!

- Get Matched with Vetted Advisors Our smart tool matches you with up to three pre-screened, vetted advisors who serve your area and are held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests. Click here to begin

- Choose Your Fit Review their profiles, schedule an introductory call (or meet in person), and select the advisor who feel is right for you.

Why wait? Start building the retirement you’ve always dreamed of. Click here to get started today!

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.