The dictionary defines “strategy” as “a plan of action designed to achieve a major goal.” In military terms, of course, the goal is almost always victory over the enemy, or at least diminution of the enemy’s power or sphere of influence.

Military strategy is nothing new. The Chinese general and philosopher Sun Tzu (544-496 B.C.) wrote an early and highly influential classic devoted to military tactics, “The Art of War.” Far closer to our own era, the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz outlined strategies that are still studied by Western armies to this day. (Here’s a roster of the greatest military geniuses in history.)

Throughout history, brilliant generals and other leaders have employed ambush, brute force, surprise attack, and various kinds of deception to further their goals on the battlefield. In many cases, these actions have resulted in victories (and defeats) that can be said to have had significant historical impact, either immediately or eventually.

To compile a list of 12 military strategies that changed the course of history, 24/7 Tempo consulted sources including Britannica, The Smithsonian Magazine, History, Holocaust Encyclopedia, and the National WWII Museum, using editorial discretion to select particularly famous and/or influential examples. The list is not comprehensive. Terrorist actions like the 9/11 attacks in the U.S. and the recent Hamas incursions into Israel, though they qualify as surprise attacks, are not included because they did not involve conventional military forces.

Some of the events described here are famous, like the Greek ruse of the Trojan Horse (which may or may not be fictional), Sherman’s March to the Sea during our Civil War, and the devastating U.S. bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. Others – for instance, the defeat of the Romans at Teutoburg Forest and the near-destruction of the Persian navy in the Straits of Salamis – may be less well-known, but are no less important. (These are the biggest surprise attacks in military history.)

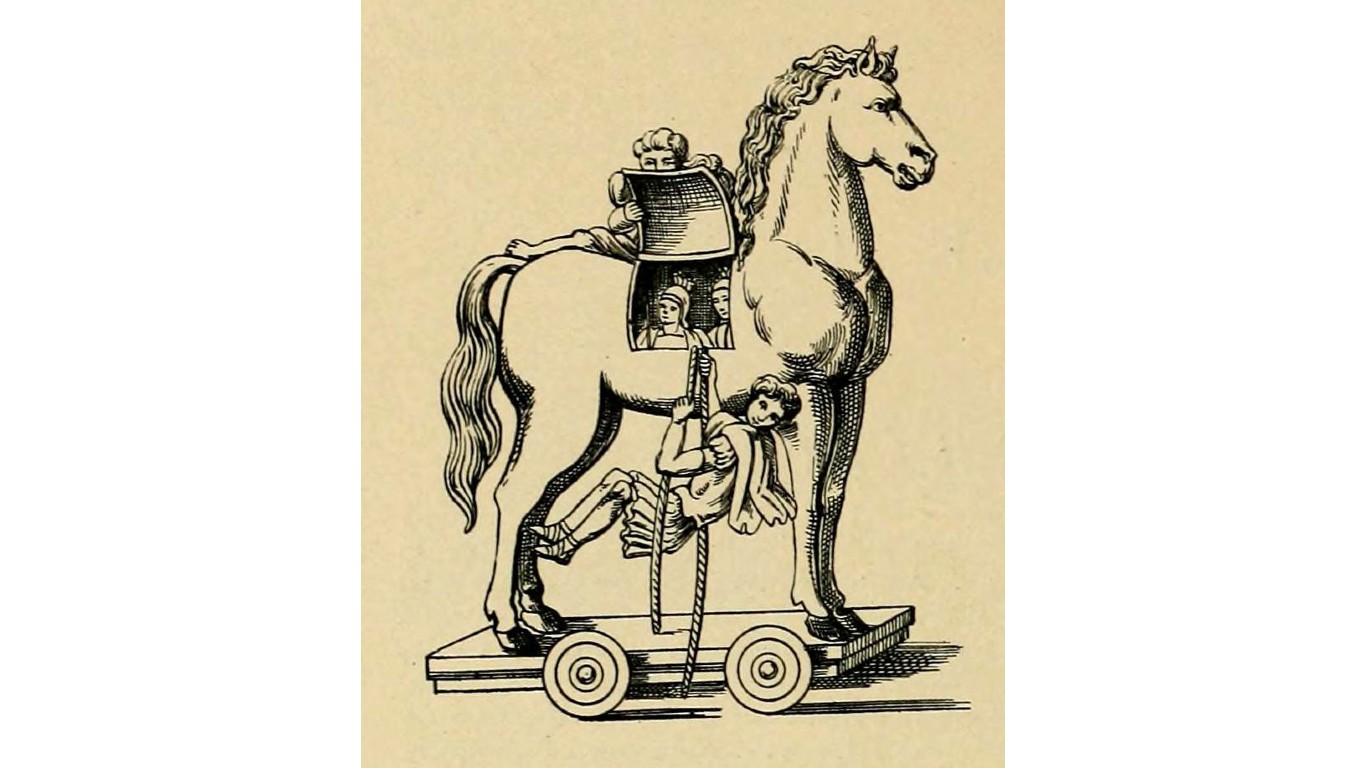

The Trojan Horse

> Where and when: Troy (present-day Turkey), 1184 B.C. (?)

Arguably the most famous example of military deception in history is the Trojan Horse – which may or may not have existed outside the chronicles of Virgil, Homer, and other bards of the ancient world. The story is that after failing to capture Troy despite a decade-long siege, the Greeks, an alliance of city-states under Odysseus, constructed a gigantic wooden horse, which they left outside the gates of the city as an apparent offering. The bulk of their forces then appeared to sail away – but some 30 soldiers remained behind, hidden inside the horse. When the Trojans brought it inside their walls, the Greeks emerged and opened the gates for the rest of their army, which had sailed back under cover of nightfall. Troy quickly fell.

The event has inspired countless works of art and literature, was considered a metaphor for the triumph of the civilized (i.e., the Greeks) over supposed barbarians (the Trojans), and marked an early example of separate political entities (the city-states) banding together for a common purpose. (And “Trojan horse,” of course, has come to mean a deal or computer program that appears to be innocuous but turns out to be malicious.)

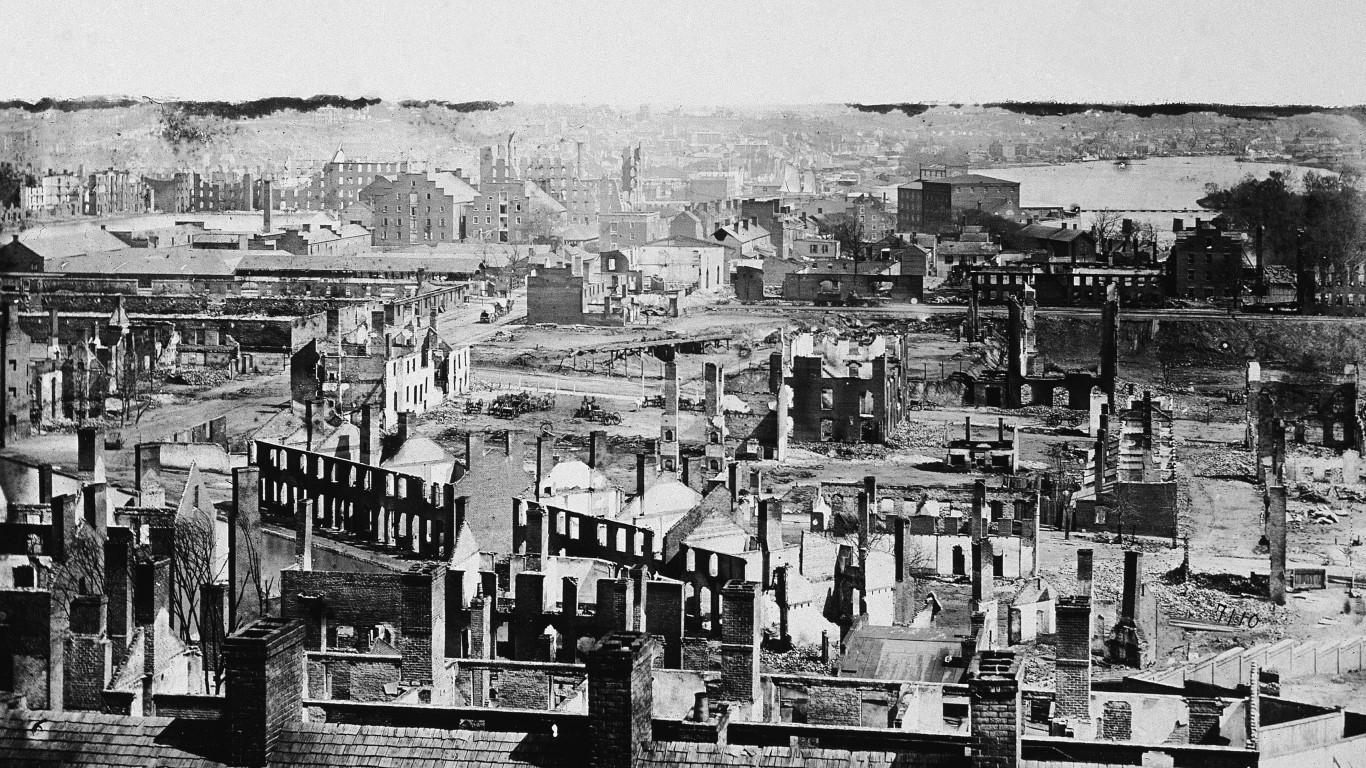

Sherman’s March to the Sea

> Where and when: Georgia, Nov. 15-Dec. 21, 1864

An example not of ambush or other subterfuge but a strategy of “total war,” this march from Atlanta to Savannah by Union forces during the Civil War, led by Major-General William Tecumseh Sherman, swept across the Georgia countryside destroying bridges, tunnels, railroad tracks, cottonfields, factories, military installations, plantations, slave quarters, and more. Historians say that Sherman’s motivation was to cripple the Confederacy with a minimum loss of life. His actions economically and psychologically weakened the Southern states, eventually leading to the Confederate surrender. The march has also been studied by historians as a vivid example of psychological warfare, and has influenced more recent military tactics. Some even credit Sherman with having invented modern warfare.

The Blitzkrieg

> Where and when: Spain, Poland, Belgium, The Netherlands, France, Soviet Union, 1936-1941

Rather than a single strategic act, the Blitzkrieg – literally “lightning war” – was a German military doctrine during World War II. The idea – echoed much later by the failed U.S. “shock and awe” attacks at the start of the Iraq War – was basically to hit the enemy with everything at once. In the case of the Germans, that meant their agile tank corps and other mechanized forces working in concert with artillery and air attacks. While the term – and the technique – came to public attention with the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939, the Germans used some of the tactics associated with it to help their Fascist allies in Spain in 1936, during the Spanish Civil War. (The proto-Blitzkrieg bombing of a town in the Basque region inspired Picasso’s epic painting “Guernica.”)

Though the Nazis were eventually ignominiously defeated, the Blitzkrieg enabled them to conquer and hold much of Europe for at least two years, and had a harrowing psychological effect even in areas they didn’t hold. It is considered a significant step in the evolution of warfare, and is said to have influenced American military doctrine even into modern times.

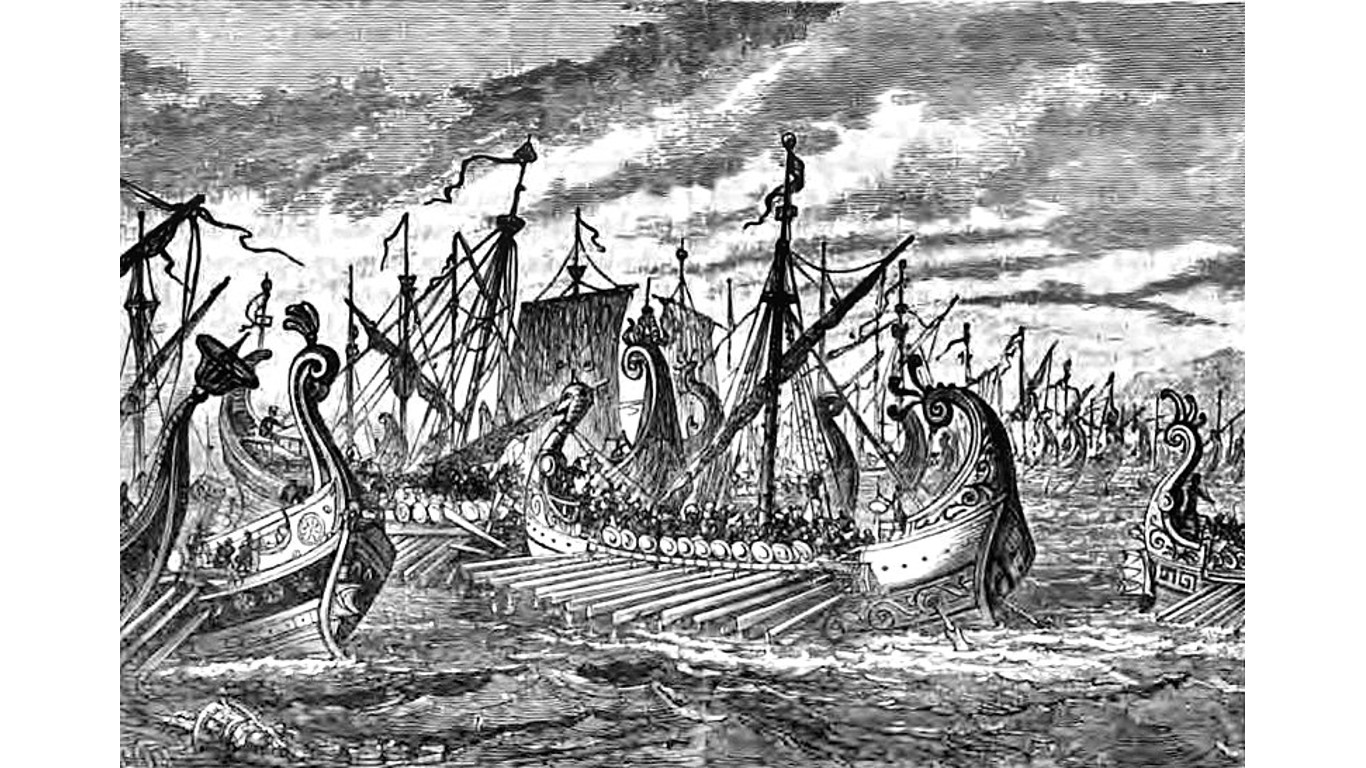

Naval ambush at Salamis

> Where and when: Straits of Salamis, Greece, Sept. 26 or 27, 480 B.C.

Not only the most important battle of the Greco-Persian Wars, but arguably one of the most important in history, this naval engagement resulted in an unexpected victory by the vastly outnumbered Greek fleet, thanks to the strategies of its commander, Themistocles. He lured the Persians to the island of Salamis, and when they arrived and attempted to blockade the Greeks in the straits between the island and the mainland, Greek ships emerged from hidden coves and attacked. Crowded into the comparatively narrow waterway, where they could not efficiently maneuver, the Persian vessels were easy prey. The battle claimed about 300 of them, while the Greeks lost only 40 of their own ships. It has been said that Western history would have been very different had the Persians won, because they would have pressed on and conquered all of Greece, suppressing the culture that ultimately gave the world so much of our science, philosophy, and systems of government.

Surprise attack on Pearl Harbor

> Where and when: Oahu, Hawaii, Dec. 7, 1941

The Japanese were intent on extending their empire into China, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific in the 1930s, and worried that the American navy might intervene. To forestall the possibility, they launched a devastating surprise attack on the Pearl Harbor headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Fleet on Sunday morning, Dec. 7, 1941 – which President Roosevelt subsequently dubbed “a date which will live in infamy.” Japanese bombers and miniature submarines appeared seemingly out of nowhere, destroying four battleships and incapacitating countless other vessels, damaging or destroying more than 300 aircraft, and killing more that 2,400 people, including 68 civilians.

How and why the Japanese were able to successfully mount the attack has never been fully explained, but a failure of military intelligence and the refusal of both military and political leaders to take the possibility of such an attack seriously were contributing factors. In any case, the day after the attack, the U.S. declared war against Japan, and a few days later, their allies Germany and Italy declared war in turn on the U.S. – and we were embroiled in one of the longest and deadliest conflicts in modern history.

George Washington crossing the Delaware River

> Where and when: Somewhere north of Trenton, NJ, Dec. 25-26, 1776

Nobody would have expected George Washington to ferry 2,400 of his troops across a river clogged with ice floes in the middle of a raging snowstorm, and on Christmas night to boot – least of all the 1,500 Hessian mercenaries serving under the British who were garrisoned at Trenton. It was a gamble, but such a desperate measure was called for, as the Continental Army’s morale was low after defeats in Long Island and northern New Jersey. The Hessians felt secure in their encampment, certain that Washington was far away, but the crossing was successful, and his troops quickly marched nine miles south to Trenton where they attacked the oblivious Hessians. More than 100 of the mercenaries were killed and almost 1,000 captured. News of the triumph reinvigorated the Continental Army’s spirits, attracted new recruits, and reassured citizens of the newly declared United States of America, inspiring the nascent nation to continue battling the British until they achieved victory five years later.

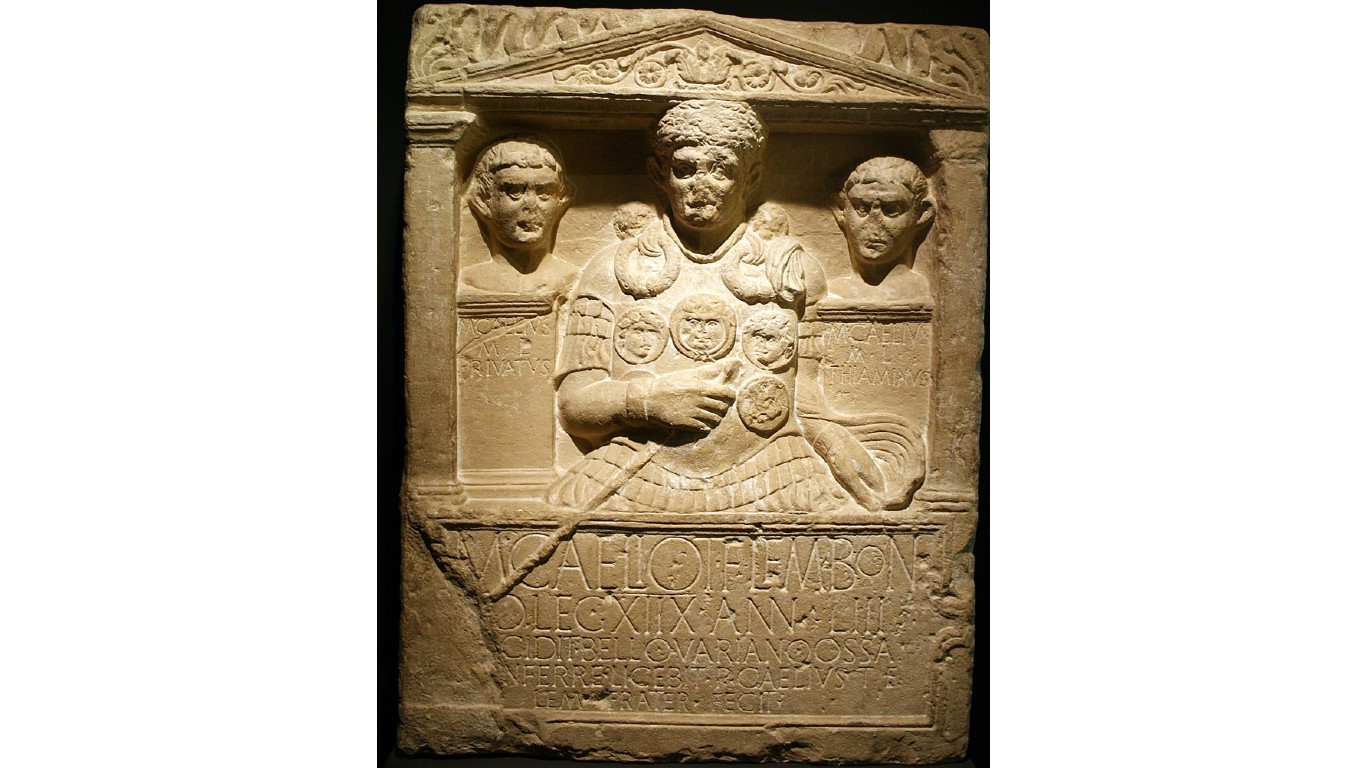

Ambush at Teutoburg Forest

> Where and when: Kalkriese (present-day Bramsche), Germany, 9-11 A.D.

In the early years of the first millennium A.D., with motives that remain unclear, a Roman-educated German soldier of fortune named Arminius convinced the Romans that an uprising against Rome’s rule was brewing in a portion of the Germanic lands. The imperial legate Publius Quinctilius Varus led a force of some 15,000 crack soldiers into the region to put the rebellion down. As they marched along a narrow trail through the forest, barbarian forces came at them from all sides, all but annihilating them (Varus committed suicide as a result of the debacle). The defeat, one of the worst ever suffered by the Romans, had lasting effects on central Europe, creating a permanent cultural and linguistic barrier between Germanic and Latin civilizations and ultimately helping to create the conditions that resulted in both world wars.

Atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

> Where and when: Southwestern Japan, Aug. 6 and 9, 1945

Controversial to this day, the stealth bombing of two cities in southwestern Japan – with horrible weapons that had never before been employed in warfare – was justified in America’s corridors of power by the fact that Japan refused to surrender, even after the Germans had put down their arms in May of ’45. Between mid-April and mid-July of the year, Japanese forces in the Pacific inflicted a particularly large number of casualties on the Allies, fighting even more fiercely as they saw defeat looming. The Potsdam Declaration, issued by President Truman and other Allied leaders on July 26, demanded that Japan surrender and warned that if it didn’t, it could expect “prompt and utter destruction.”

The Japanese refused to reply, and within a few days, American B-29 bombers jolted the world by dropping atomic bombs on the two cities. More than 200,000 Japanese citizens were probably killed between the two cities, either immediately or from the effects of radiation. On Aug. 15, Japan’s emperor, Hirohito, announced his country’s unconditional surrender. Besides ending the war and preventing further loss of life, the bombings set the stage for an escalation of the nuclear age, whose effects are still felt today.

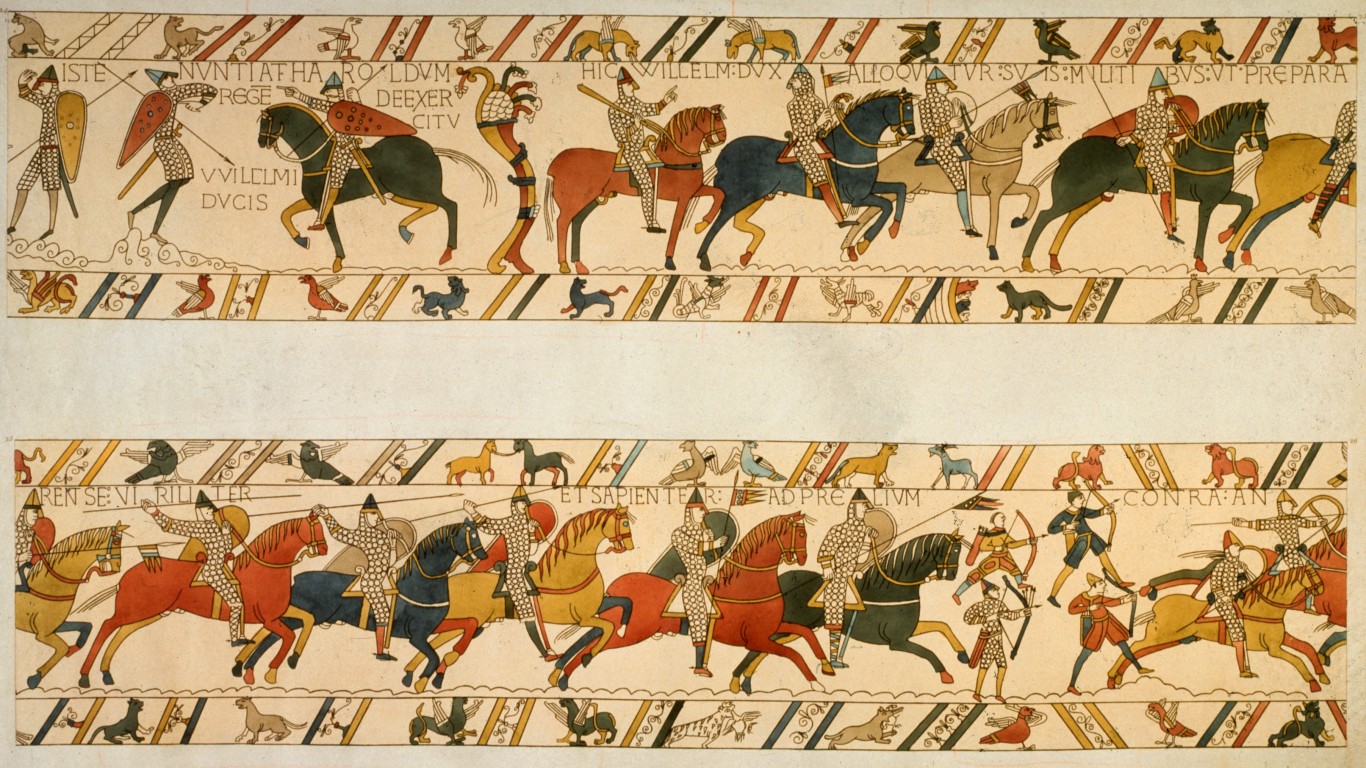

William the Conqueror’s fake retreat at the Battle of Hastings

> Where and when: Hailesaltede, near Hastings (in present-day East Sussex, England, Oct. 14, 1066

William, the Duke of Normandy – who later earned the title of William the Conqueror – believed that the throne of England rightfully belonged to him and not to the recently installed Anglo-Saxon English king Harold Godwinson. About two weeks after successfully landing a large force of troops at Pevensey, near Hastings, William faced Harold in battle. The English army occupied high ground, behind an unbroken wall of shields. After William failed at an attempt to breach their defenses, he led his men into a feigned retreat. This tempted some of the English to pursue them, but once they had left their positions, they were vulnerable to William’s cavalry, and those who remained in the weakened shield wall were easy prey for his infantry. Harold was killed during the battle, and William, after further smaller battles, was crowned King of England on Christmas Day.

William’s victory, according to the website Historic UK, meant that “England would henceforth be ruled by an oppressive foreign aristocracy, which in turn would influence the entire ecclesiastical and political institutions of Christendom.” Beyond that, under the Normans, the French language infiltrated English to an astonishing extent. It is estimated that by 1400, one in five English words derived from French, and the influx has given us a rich range of synonyms in which one derives from Anglo-Saxon and one from French – for instance “kingly” and “royal,” “lawyer” and “attorney,” “weird” and strange,” and “belly” and “stomach.”

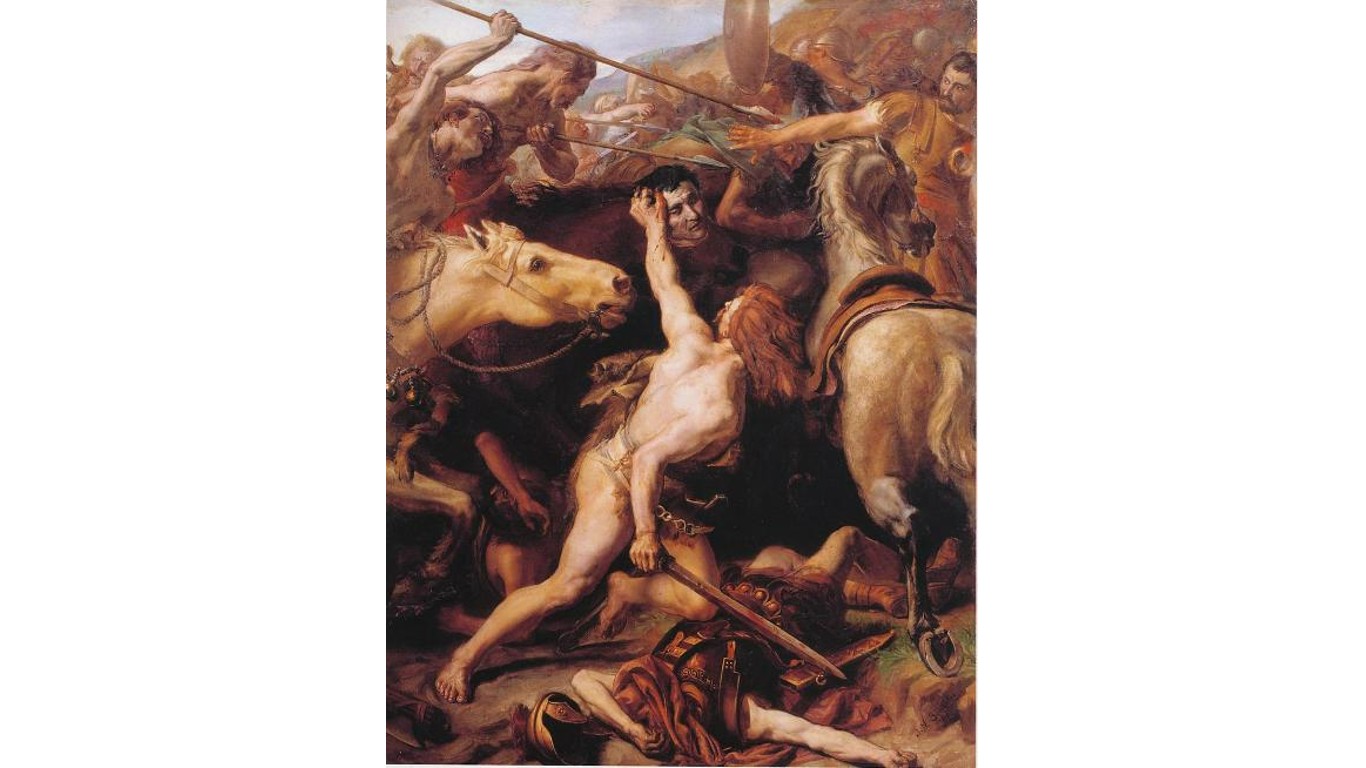

Hannibal’s ambush of the Romans at Lake Trasimene

> Where and when: Umbria (present-day Italy), June 21, 217 B.C.

The celebrated Carthaginian general Hannibal, considered one of history’s greatest military figures, famously invaded Italy by leading his forces, including 80 “war elephants” from North Africa, over the Alps during the Second Punic War. Descending down the peninsula into Umbria, he met the Roman army around Lake Trasimene (now Lake Trasimeno). His strategy was to harass the Romans with small groups of soldiers, taunting them to follow their attackers down a narrow road between the lake and a dense forest. The Carthaginians then surged out of the forest, in what has been called “the greatest ambush in history,” reportedly killing half the Romans and taking the other half prisoner.

Following another defeat by the Carthaginians at Cannae the following year, the Romans appointed Quintus Fabius Maximus as dictator for a six-month period in an attempt to avoid further defeats. Fabius pursued a unique strategy of his own, avoiding direct conflict with the enemy and instead harassing them in minor engagements and disrupting their supply lines. This became known as the Fabian Strategy, and the tactic was later employed by numerous military leaders, from George Washington to North Vietnamese generals during the Vietnam War.

Deception of the Germans before D-Day

> Where and when: Various locations, July 14, 1943- June 6, 1944

In planning the invasion of Nazi-held France from the beaches of Normandy, the U.S., the U.K., and their allies conceived a broad strategy of deception, involving five separate operations, codenamed Operation Bodyguard. The intention was to make the Germans believe that the invasion would come later and in different locations. Meeting in Tehran, Cairo, London, and elsewhere, the Allies made plans to leak false information, hold phony exercises, and even employ parachuting dummies and inflatable tanks to suggest troop build-ups in areas far from Normandy. Though troops landing in Normandy on D-Day faced heavy fighting and a days-long battle, Operation Bodyguard was considered a success, delaying deployment of larger German forces to the area for weeks. The invasion led to Allied victory on the Western Front, an important step towards the defeat of the Nazis almost a year later.

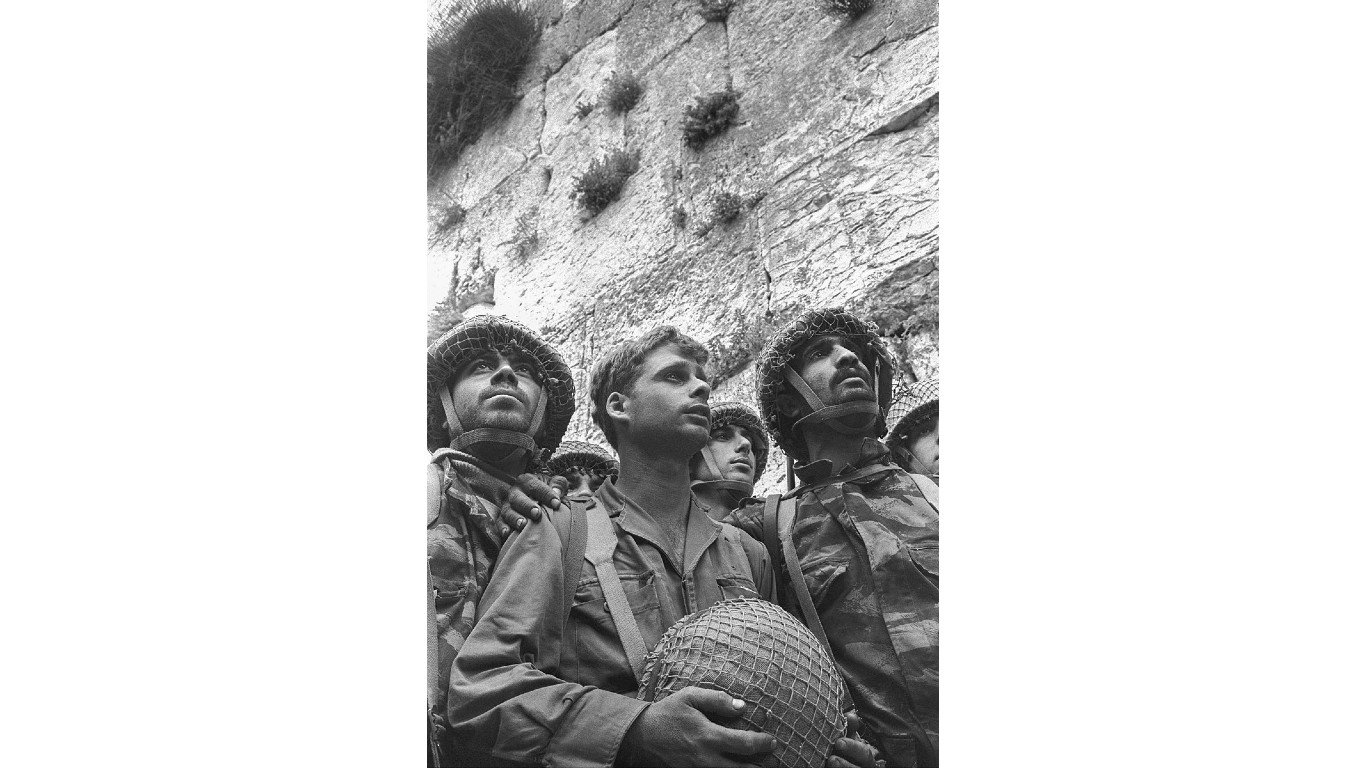

Israel’s preemptive strike against the Arab world

> Where and when: Portions of Egypt, Syria, Jordan, etc., June 5-10, 1967

As tensions grew between the 19-year-old state of Israel and Egypt and its neighbors over the closing of a shipping channel vital to Israeli interests, Palestinian guerrilla attacks, and other issues, Israel feared escalation of hostilities – so launched a preemptive bomber attack on Egyptian air force bases and other facilities and a simultaneous ground invasion of the Egyptian-occupied Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip. Other Arab nations, primarily Syria and Jordan, joined Egypt in fighting back, and hostilities raged for six days, ultimately claiming almost 20,000 lives, overwhelmingly on the Arab side. Israel emerged victorious, having established itself as a major military force in the region, as well as gaining territory that quadrupled it in size (at least temporarily), displacing about a third of the Palestinians who’d been living in Gaza and the West Bank, and redrawing the map of a portion of the Middle East, with consequences we see playing out so tragically today.

100 Million Americans Are Missing This Crucial Retirement Tool

The thought of burdening your family with a financial disaster is most Americans’ nightmare. However, recent studies show that over 100 million Americans still don’t have proper life insurance in the event they pass away.

Life insurance can bring peace of mind – ensuring your loved ones are safeguarded against unforeseen expenses and debts. With premiums often lower than expected and a variety of plans tailored to different life stages and health conditions, securing a policy is more accessible than ever.

A quick, no-obligation quote can provide valuable insight into what’s available and what might best suit your family’s needs. Life insurance is a simple step you can take today to help secure peace of mind for your loved ones tomorrow.

Click here to learn how to get a quote in just a few minutes.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.