The devastating wildfires consuming Los Angeles have driven home to the world the intensity of the water crisis in California and other southwestern states. A decades-long drought has inspired all sorts of suggestions for fixes. However, California already has the water it needs in-state if it can find the political will and funding to use it.

California’s water crisis is difficult to solve, but the state has internal resources that could be reconfigured to relieve the worst of the crisis. Retiring early is possible, and may be easier than you think. Click here now to see if you’re ahead, or behind. (Sponsor)

Key Points

California’s Water Usage

California has the largest and most expensive water system in the world, serving about 40 million people and 5.68 million acres of farmland. The economy of the state generates a GDP of $3.9 trillion a year, larger than that of the United Kingdom. So it’s understandable that it needs a lot of water.

About 50% of the state’s water resources go back into the environment, 40% is used for agriculture, and 10% for the urban and suburban population. These ratios mean that, while conservation by citizens is crucial, the main areas where much more water could be made available are in the environmental and agricultural areas.

California’s Climate

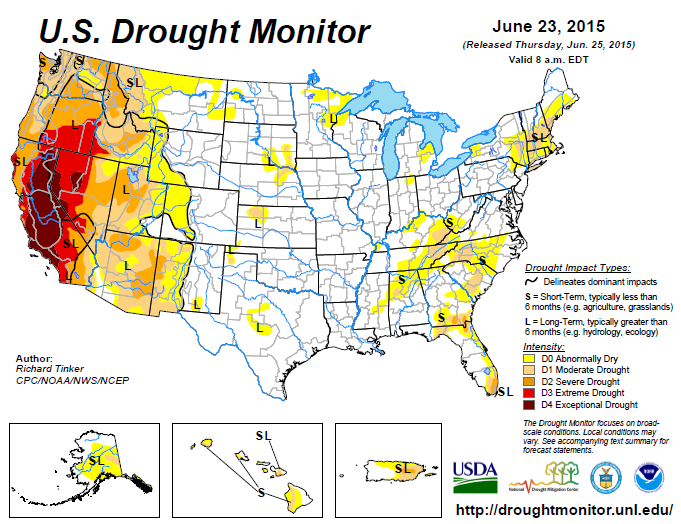

This map illustrates a particularly intense drought period in California and neighboring states in the summer of 2015. Updated maps available at U.S. Drought Monitor indicate that the state is not currently in full-scale drought, but this cannot be expected to last. California has always gone through cycles of drought, as seen not only in recorded history, but in data from tree rings and geology going back thousands of years into prehistory. Climate change has exacerbated the issue with unpredictable and extreme weather patterns.

The Declining Colorado River

The Colorado River serves 7 western states and Mexico. The state of Colorado pumps water from the headwaters through 20 or so tunnels in the Rocky Mountains to serve the needs of Denver, Boulder, and other cities on the eastern side of the Continental Divide. The drought is not as severe in some of the upstream states, so there is not as much urgency for extreme conservation measures.

Lake Powell in Utah and Lake Mead in Nevada/Arizona are major reservoirs on the river providing hydroelectric power and water for millions of people. The levels of both are 120-160 feet below full capacity, so low that their ability to continue generating power is threatened. There has been talk of releasing Lake Powell’s water to prioritize Lake Mead, downstream, which serves more people.

California and Mexico’s Use of the Colorado

California is the last state to get Colorado River water, but by negotiation among the states, it receives the largest allotment. Most of it is used for agriculture in the Imperial Valley, a major food-growing area for the state and the nation that extends down to the Mexican border. By treaty the last 10% of the river’s water runs into Mexico. It’s used mainly for agriculture and with so little remaining, it rarely reaches the ocean anymore.

Population Pressure

Overpopulation in the arid Southwestern climate is a significant factor in the water crisis as well. California has a population of about 40 million today, forecast to increase to 50 million in the next 25 years. Even when people do move out of crowded Southern California, thousands relocate to Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, and Wyoming, continuing to place demands on the Colorado River watershed.

Conservation Efforts

Western states are implementing various water conservation efforts including:

- Public awareness campaigns and resources to educate and assist citizens, farmers, and businesses to optimize efficient water use.

- Mandatory regulations requiring urban water suppliers to limit what they supply to meet water reduction targets.

- Rebate programs to encourage homeowners and businesses to remove grass and landscape with sand, rocks, and desert flora.

- Programs to promote efficient irrigation in agricultural areas.

What Else Could California Do?

The California state government gets plenty of criticism for its handling of the water crisis and numerous other issues affecting such a huge and heavily populated state. It has already created extensive infrastructure and an administrative framework to use water efficiently. But there’s no doubt that local, state, and federal budgetary priorities, environmental regulations, and bureaucracy could be realigned to make a greater impact on this critical issue. Here are some areas where in-state resources could make a difference.

Areas For Continued Improvement

Some of the areas that have been suggested where California could continue to improve its usage of water include:

- Improving infrastructure for wastewater management, including stormwater and runoff.

- Modernize reservoirs and aqueducts and building new ones to reduce losses from leaks and evaporation.

- Research and implement desalination technology, particularly for brackish groundwater which has less salt content than ocean water.

- Water rights are complicated in California and often based on historical claims rather than current needs. This is an area in need of reforms.

- Coordination of federal, state, and local administrations and policies could improve water management.

Capturing California’s Rivers

About 75% of California’s water resources are in the northern half of the state, while 80% of the demand is in the southern 2/3rds. California has 7 major rivers, mainly in the north, that dump a total of about 46.68 million acre-feet a year into the ocean. Meanwhile, the estimated annual water deficit of the state is somewhere between 2-6 million acre-feet. A rather obvious solution, then, is to pipe 10% of the water from the northern part of the state to the south. So why isn’t that happening?

Obstacles to Using Northern California’s Water

Moving northern Californian water to the south is by no means a new idea, and it certainly makes more sense than schemes to pump water from the Mississippi River across the country and over the Rocky Mountains to replenish the Colorado. Here are some of the obstacles standing in the way:

- Geography. California’s terrain is rugged and earthquake-prone, and the distance to be covered by a pipeline is hundreds of miles. Building tunnels and elevated aqueducts would be an engineering challenge and would do environmental damage along the way.

- Cost. The cost of such a plan would run well into the billions of dollars, and ongoing maintenance would also be costly.

- Bureaucracy. Water rights in California are controversial, rooted in historical claims, and complicated by Federal and State regulations. It would be politically difficult to get agreement from all the layers of government.

- Local opposition. Local communities, farmers, and Native American tribes often oppose the export of their resources and the use of eminent domain to take private property for public construction projects.

The San Joaquin River

The San Joaquin River flows through the southern end of California’s Central Valley before discharging into San Francisco Bay at an estimated rate of 1.5 to 2 million acre-feet of water a year. This amount of water could go a substantial way to relieving Southern California’s needs and would be a shorter distance to pipe water than bringing it from the north.

Due to environmental damage, it would not be politically acceptable to use up all the river’s resources so that it dries up at the mouth like the Colorado does. But those concerns can be balanced with the needs of the population to the south. And if reservoirs and water diversion infrastructure were set up, more of the river’s water could be captured and diverted in rainy times such as 2023.

Free Market Solutions

Ultimately, the most efficient way to solve California’s water crisis may be through the free market. On average, Californians pay about $50-$100 a month for water services, differing based on the time of year, drought conditions, local surcharges, and the amount of water used. The price of water in thirsty parts of the state could be raised substantially to encourage conservation by individuals and businesses.

Every family should have access to the basic amount of water necessary to live there, but the price could be raised substantially for above-average uses to make it prohibitive for many people to wash cars, water lawns, or maintain a swimming pool unless they had the money to do so. Agriculture and industry could pay much higher rates, with revenues used to invest in improved water infrastructure. Individuals or businesses who find the rates too high would be incentivized to conserve water or to relocate to someplace without such high rates: such as Northern California.

No Easy Solutions

There are no easy solutions to such a complex problem that involves multiple states and local jurisdictions as well as the federal government, pits urban and rural areas against one another, and threatens the environment on land and at sea. Looking just at resources within California, though, reforms to regulations and bureaucracy, prioritizing this crisis over other concerns and budgeting accordingly, reallocating water resources already in the state, and raising the price of water to incentivize conservation and fund infrastructure are all ways California could get it own house in order before looking out-of-state for solutions.

Get Ready To Retire (Sponsored)

Start by taking a quick retirement quiz from SmartAsset that will match you with up to 3 financial advisors that serve your area and beyond in 5 minutes, or less.

Each advisor has been vetted by SmartAsset and is held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests.

Here’s how it works:

1. Answer SmartAsset advisor match quiz

2. Review your pre-screened matches at your leisure. Check out the advisors’ profiles.

3. Speak with advisors at no cost to you. Have an introductory call on the phone or introduction in person and choose whom to work with in the future

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.