There will, of course, be ups and downs in crude oil, just as there are with all commodities — volatility comes with the territory. But the trend is up and to the left, and Watson’s point is that based on rising production costs, the oil companies need prices no lower than $100 a barrel in order to pay the ever-rising costs associated with getting crude from ultradeep water and tight shale formations on land. One hundred dollars a barrel is a floor; no one knows where the ceiling is.

Decreasing demand for crude oil in developed countries has been offset by swelling demand from emerging countries, particularly China. But that growth is relatively small, and globally supply and demand are currently able to remain roughly in synch. In order to maintain a reasonable profit, the oil companies need demand to rise to cover the higher costs they are paying for production. But even in China demand growth is slowing down.

By one estimate, in the decade to 2012, production costs rose fourfold in nominal terms while production rose just 11%. The economics of such a situation cannot last forever — and they didn’t.

When demand for crude was strong, say seven or eight years ago, oil companies could absorb the higher costs to boost production and still turn in record profits. Then, as the old saying predicts, the best cure for high prices was high prices.

Chevron, Exxon Mobil Corp. (NYSE: XOM) and Royal Dutch Shell PLC (NYSE: RDS-A) have all announced significant reductions in capital spending over the next several years as they work to bring spending in line with revenues. Initially the price increases will be moderate, but eventually demand will outstrip supply again and crude prices could easily take off once more.

U.S. oil producers argue that removing the ban on oil exports will help them to recover their rising costs because they can charge more for the crude. That will be true for two or maybe three years, but again crude prices will settle around a level where demand and supply once more become roughly equivalent.

There is also an argument that proposed changes in the crude futures market in the United States make it increasingly risky for oil companies to spend on new production. Non-commercial traders (aka, speculators) will soon be subject to position limits and to capital requirements that have already chased some of them from the futures market. Without traders willing to take the long side of the trade, the oil companies have no ability to hedge production. That means that the companies must absorb virtually 100% of the price risk on forward barrels.

Investors in Chevron and Exxon will be the short-term beneficiaries here, just as investors in mining companies have benefited from the sharp pullbacks in the capital spending of miners. Less spending and reduced costs translate into more share buybacks and dividend increases as the oil and mining companies work to keep stock prices high in order to maintain access to the capital markets.

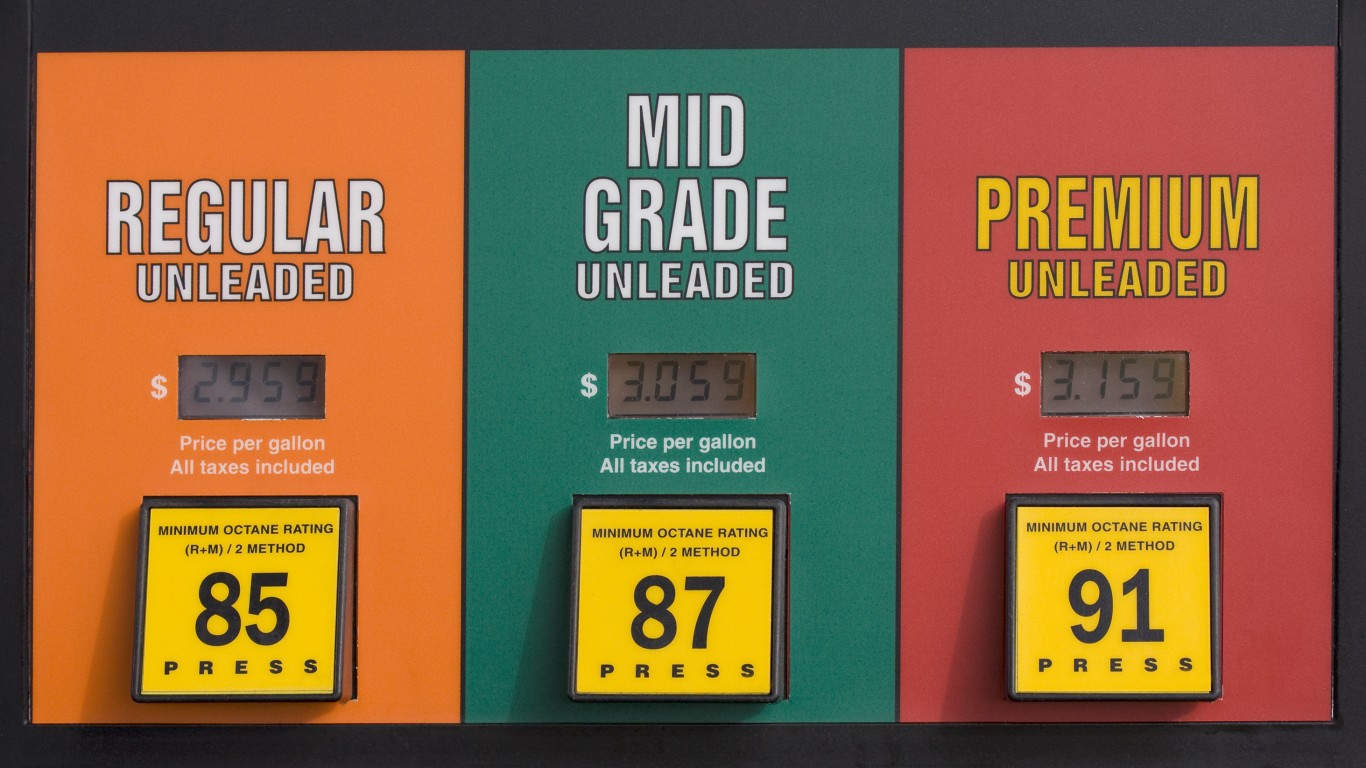

For consumers there is no chance that we will ever see gasoline pump prices below $2.50 a gallon, and only a very slim chance that prices will ever again fall below $3.00 a gallon for an extended period. That is the message Chevron CEO John Watson had for consumers.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.