A week ago, Russia rejected Saudi Arabia’s recommendation to cut an additional 1.5 million barrels a day of crude oil production in an effort to push prices higher. Over the weekend, the Saudis announced that they would produce flat out, flooding the market with even cheaper crude.

The Saudis want to reassert their dominance in world oil markets, bring the Russians back into the OPEC+ coalition, and force the U.S. president to intervene on behalf of U.S. oil producers, particularly shale oil producers. The Saudi goal is to boost market share and prop up prices.

The squeeze on U.S. oil companies is tight and getting tighter. While prices are the most immediately obvious, it’s worth taking a look at where else the pressure is coming from.

A recent examination by energy research firm Rystad Energy points out that drilled but uncompleted wells (DUCs) will be the first shale assets threatened by the new low-price environment. Rystad believes the breakeven price for these wells is around $25, only a few dollars below the lowest Brent price during the past week. If Brent falls below $25 a barrel (certainly possible), those shale DUCs become uneconomic.

With oil prices at around $35 for Brent and $30 for West Texas Intermediate (WTI), Rystad reckons that production in the Lower 48 would continue to grow through the summer by around 200,000 to 300,000 barrels per day above current levels and would begin to decline in the fourth quarter of this year. If the price of WTI remains around $30, Rystad estimates 1 million barrels a day will be at risk by December and 2020 daily production would end the year about where it started.

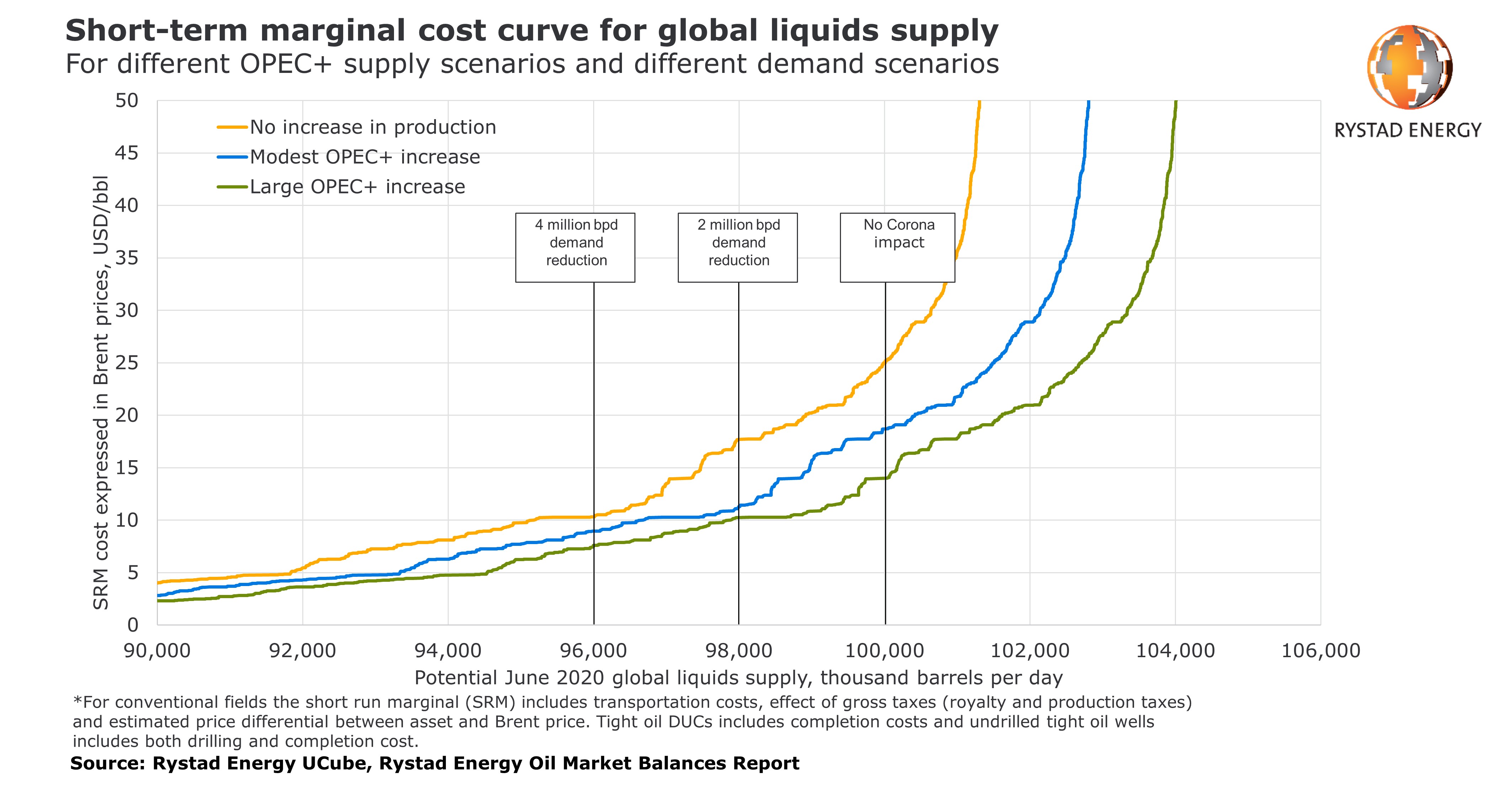

The scale of the implied increase in production from Russia, Saudi Arabia and the other members of what was OPEC+ is a second problem. Rystad estimates that global supply could increase by 1.5 million to 2.5 million barrels a day in the short term. Using a pre-coronavirus estimate of global demand totaling 100 million barrels a day, the firm calculates the short-term marginal cost if demand were to remain at that level (unlikely) or fall by either 2 million or 4 million barrels a day. The following chart shows the short-term marginal (SRM) cost curves under three scenarios.

Here’s how the firm calculates the short-term costs:

For conventional fields, the SRM only includes transportation costs, effects of gross taxes and price differentials to Brent. All other costs, such as production cost and investments, are excluded, as Rystad Energy believes that these costs will not affect production levels from producing fields in the short term. For tight oil assets, producing wells include the same costs as conventional fields, while the drilled uncompleted wells (DUC wells) also include the costs for completing the wells. For not yet drilled tight oil wells, both drilling and completion costs are included.

A drop in demand of 4 million barrels a day coupled with an increase in production by former OPEC+ members of 2.5 million barrels a day, drives the SRM down to around $7.50 a barrel. Completing a DUC or drilling a new shale well pushes the cost higher for shale producers. At less than $30 a barrel for WTI, profits may entirely disappear.

A third pressure point is producer hedging. Goldman Sachs estimates that about 43% of expected 2020 shale production was hedged at around $50 a barrel. With prices in the low $30-range, it would seem that those insurance policies would pay off.

However, this is the oil business and nothing is that simple. Not all hedges simply lock in that $50 price. A common variant is a hedging strategy known as a three-way collar. In this strategy, the producer purchases put (sell) options at $50 as insurance and also purchases call (buy) options at a lower strike price to offset some or all the cost of the put options.

Basically, a three-way collar is a bet that the price will fall to a specific level below $50 (say, to $45), but no further. If the call option falls below that $45 level, the producer is fully exposed to the lower price. RBC Capital Markets said that Marathon Oil Corp. (NYSE: MRO) and Pioneer Natural Resources Inc. (NYSE: PXD) had three-way collars on 38% and 54%, respectively, of estimated 2020 production.

One producer, Occidental Petroleum Corp. (NYSE: OXY) may be in a particularly difficult position. According to a Reuters report, Oxy protected its 2020 selling price for 2020 down to a Brent price of $45 a barrel in exchange for leaving itself completely exposed to all downside risk in 2021.

Earlier this week, Oxy cut its dividend by 86% and its capital expenditure budget by about a quarter in an effort to preserve cash. Some of that cash is going to have to be used to cover non-performing hedges or to pay to unwind them.

U.S. equities traded higher Friday morning, up by around 3%, and WTI crude traded up more than 2.5% at $32.32 a barrel while Brent traded up about half as much at $35.63.

Get Ready To Retire (Sponsored)

Start by taking a quick retirement quiz from SmartAsset that will match you with up to 3 financial advisors that serve your area and beyond in 5 minutes, or less.

Each advisor has been vetted by SmartAsset and is held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests.

Here’s how it works:

1. Answer SmartAsset advisor match quiz

2. Review your pre-screened matches at your leisure. Check out the advisors’ profiles.

3. Speak with advisors at no cost to you. Have an introductory call on the phone or introduction in person and choose whom to work with in the future

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.