U.S. benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil dropped by 18% in the noon hour Wednesday to post a price not seen since 2002. WTI hit a low of $22.04 a barrel less than two hours after the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) released its report on last week’s oil inventories.

The EIA reported that crude oil inventories rose by 2 million barrels to 453.7 million barrels, about 3% below the five-year average. Inventories of gasoline fell by 6.2 million barrels last week, and diesel inventories dropped by 2.9 million barrels.

In a normal week, those numbers, combined with a refinery run-rate at 86.4% of capacity, would have boosted the price of WTI. But supply is not the problem. The price crash is entirely due to a lack of demand and fears of even lower prices to come.

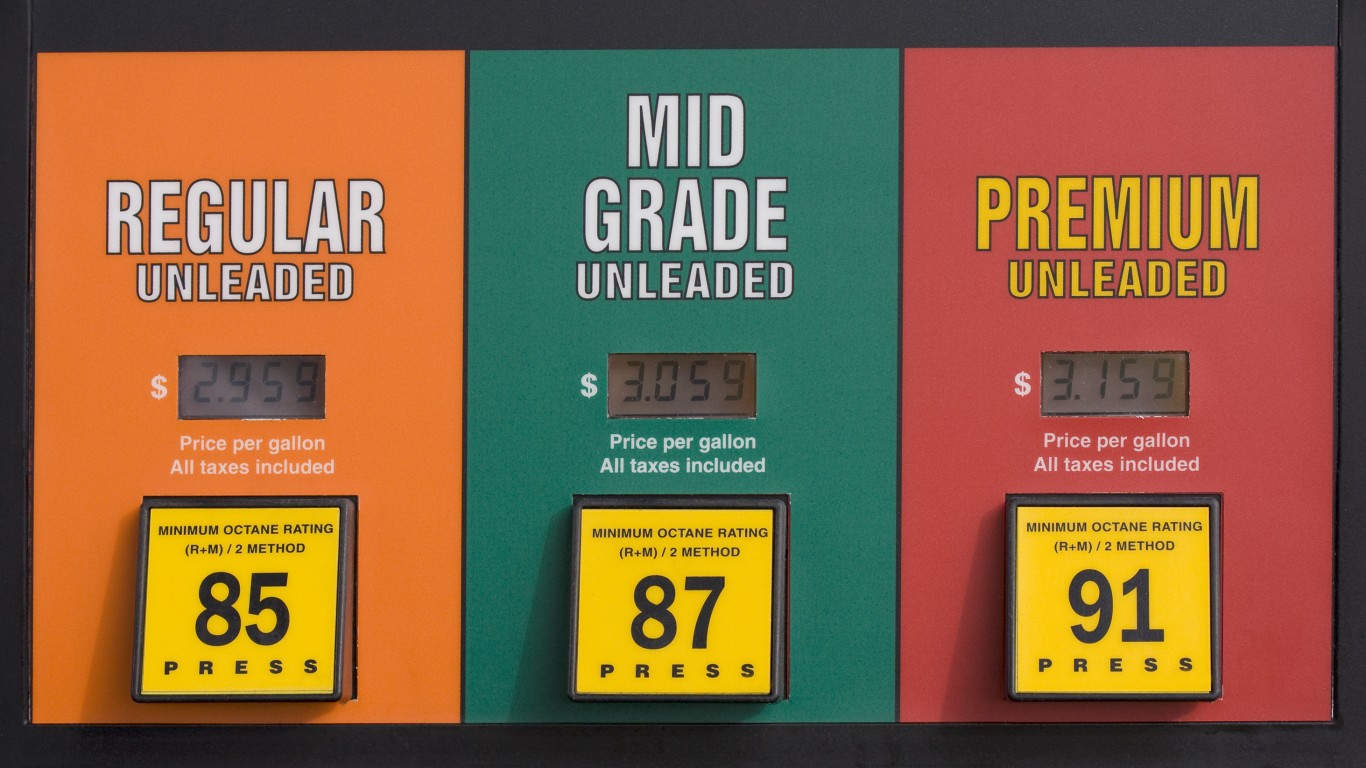

The spread of coronavirus (now present in all 50 states) has stifled demand. As more and more areas of the country lock down citizen travel, ever fewer Americans will be driving to work, the store or school, or anywhere. Normally, pump prices zeroing in on $2.00 a gallon would put more Americans on the road. This time is different.

Saudi Arabia’s strategy to flood the market with crude oil in an effort to increase its market share has knocked nearly 50% off the price of benchmark Brent crude in just two weeks. Brent sold for $51.86 a barrel on March 2 and traded Wednesday morning at a low of $25.98. Saudi Arabia has committed to continuing production of 12.3 million barrels of oil a day “over the coming months,” according to a statement from the country’s energy ministry.

The impact of the Saudi push for market share and Russia’s determination to play the same game is devastating to the U.S. shale industry. Chevron Corp. (NYSE: CVX) and Exxon Mobil Corp. (NYSE: XOM), now among the leaders in shale production, traded down 12.8% and 8.3%, respectively, Wednesday morning. The S&P 500’s energy sector traded down 11.6%, leading an overall drop of around 7% in the index.

The question on nearly everyone’s mind (if not their lips) is, “How long can this go on?” By some estimates, before the price slide is stopped, demand will have to fall by 10 million barrels a day. Goldman Sachs estimates that demand has already fallen by 8 million barrels, so that could indicate that the price of WTI may break its fall at around $15 to $18 a barrel.

The Saudis appear to be satisfied with lower prices for months. They claim that Saudi Arabia can make a profit even if prices fall to around $10 a barrel. We all may get to find out.

The bad news is that at less than $25 a barrel, new shale wells are uneconomic; that is, they can’t be drilled, completed and pumped at a profit. Costs at already producing wells may be able to turn a profit with oil at that level. Unfortunately, shale wells produce at their maximum levels within a year and production drops significantly in the second year and trails ever lower over the next several years.

The only way to keep production up is to keep drilling new wells, but that’s expensive, and many smaller shale producers borrowed heavily in 2015 and 2016 to ramp up production when the Saudis tried this strategy the first time.

While the Saudi plan may drive weaker shale players out of business this time around, the oil will still be in the ground. As prices rise again (that’s the ultimate goal the Saudis’ current play for market share), Exxon and Chevron and any other survivors should be able to produce the shale oil at a profit.

The U.S. president has ordered the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to purchase barrels to top up the reserve, but this won’t help much. The Reserve’s capacity is 713.5 million barrels and there are 635 million barrels already in storage. Over the course of the past 12 months, the federal government actually has sold 14.2 million barrels from the reserve in an effort to help offset the federal deficit. Adding fewer than 80 million barrels to the reserve amounts to less than a week of current U.S. production.

There will be more pain in the U.S. oil patch over the next six to nine months, at least. Once the coronavirus threat is contained (and some epidemiologists say that could take 12 to 18 months), the world’s oil producers are going to have to deal with a slow but inexorable decline in demand for oil as the world shifts to electrified vehicles. Right now, however, oversupply and lack of demand are set to crush oil prices as the world turns its attention and resources to combat a pandemic.

Get Ready To Retire (Sponsored)

Start by taking a quick retirement quiz from SmartAsset that will match you with up to 3 financial advisors that serve your area and beyond in 5 minutes, or less.

Each advisor has been vetted by SmartAsset and is held to a fiduciary standard to act in your best interests.

Here’s how it works:

1. Answer SmartAsset advisor match quiz

2. Review your pre-screened matches at your leisure. Check out the advisors’ profiles.

3. Speak with advisors at no cost to you. Have an introductory call on the phone or introduction in person and choose whom to work with in the future

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.