In June of 2022, the price of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) reached an inflation-adjusted high of $120. By June of this year, the price had dropped to an inflation-adjusted price of $71 a barrel. Just three months later, the September price had jumped back to $89 a barrel. (These nine crises threaten the global economy.)

The price increase is largely the result of production cuts from Saudi Arabia and Russia. The two OPEC+ members have agreed to reduce production by 1 million barrels a day at least through the end of the year, and maybe longer. WTI traded at just under $83 a barrel early Thursday morning.

Total U.S. crude production reached 12.99 million barrels a day this past July, essentially equal to the all-time high U.S. production of 13 million barrels a day in November 2019. Excluding Gulf of Mexico production, oil production reached 10.7 million barrels a day in July, a new record.

Since that high point, both prices and production had slowly declined, but the price boost generated by the Saudis and the Russians have sent exploration and production companies back on the hunt for more oil.

Reuters energy reporter John Kemp explains what is happening:

Higher prices have boosted cash flow and improved confidence in the short and medium term outlook for shale producers.

Production cuts by Saudi Arabia and Russia have thrown a lifeline to the U.S. shale firms, helping them avoid a much deeper downturn.

U.S. crude output is now more likely to stabilise than decline through the end of 2023 and the first half of 2024 as a result of OPEC⁺ restraint.

In turn, the largest U.S. shale producers have indicated they have no intention of raising output in response to the recent rise in prices.

WTI prices dropped by $5 a barrel on Wednesday after the U.S. Energy Information Administration reported that the nation’s gasoline inventories rose by 6.5 million barrels last week. Crude production rose to 12.9 million barrels a day, up 4.3% compared to the same week last year.

OPEC+ announced that it would maintain its production cuts, a move the cartel expected to prop up prices. It did not work.

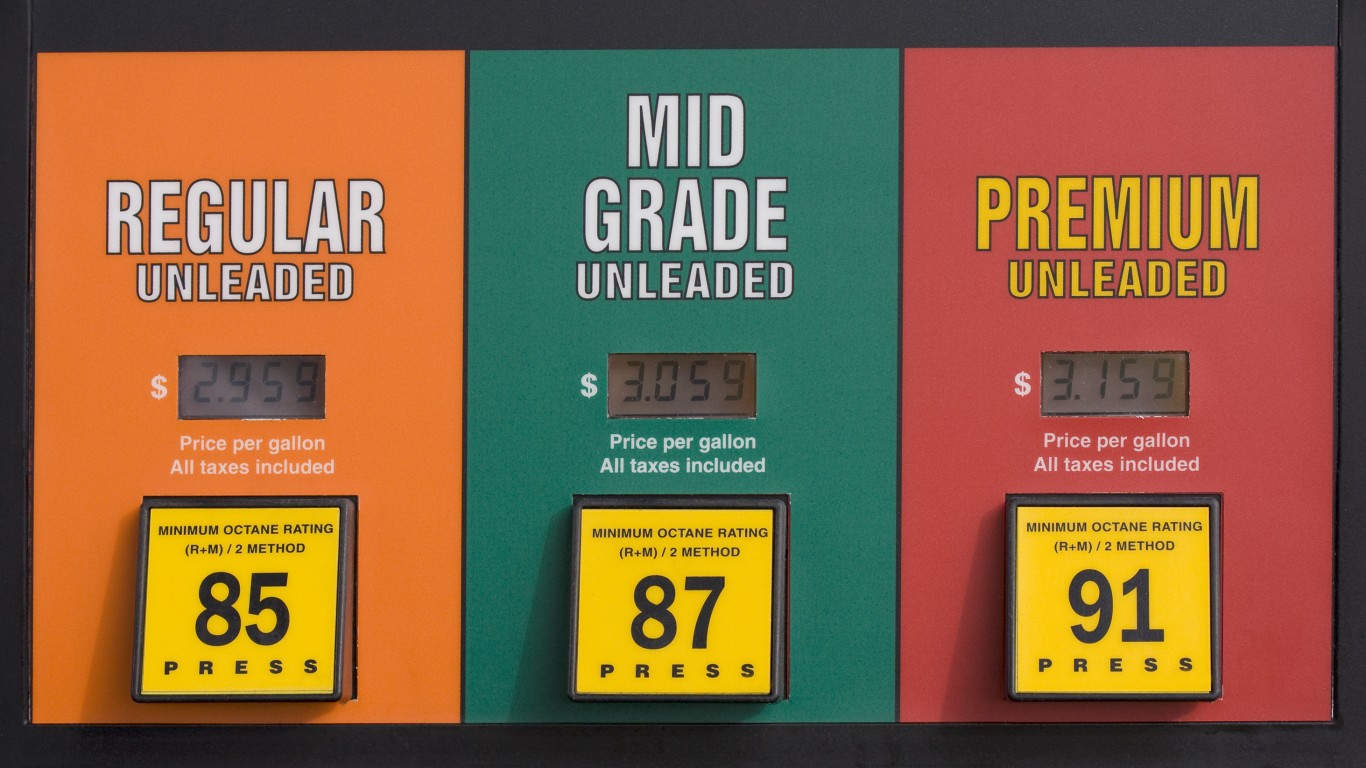

Pump prices will begin to decline, but much more slowly than they rose. Gas stations will want to wait as long as possible to take delivery of the new, cheaper gasoline. Then gas stations will refill their supplies only partially, another way to keep prices higher for longer (sound familiar?).

But what about crude prices, down $10 a barrel in less than a week? Refer to the earlier comment from John Kemp: “The largest U.S. shale producers have indicated they have no intention of raising output in response to the recent rise in prices.” Because they know the price will fall and they do not want it to fall too far.

It’s Your Money, Your Future—Own It (sponsor)

Retirement can be daunting, but it doesn’t need to be.

Imagine having an expert in your corner to help you with your financial goals. Someone to help you determine if you’re ahead, behind, or right on track. With SmartAsset, that’s not just a dream—it’s reality. This free tool connects you with pre-screened financial advisors who work in your best interests. It’s quick, it’s easy, so take the leap today and start planning smarter!

Don’t waste another minute; get started right here and help your retirement dreams become a retirement reality.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.

24/7 Wall St.

24/7 Wall St.