Special Report

What It Was Like to Work in America's First Factories

Published:

Last Updated:

When we think of factories, we probably think of assembly lines staffed by workers performing repetitive tasks — or, increasingly, of sophisticated robotic machinery cutting, shaping, assembling, and packaging whatever products are being made. In past centuries, though, factories were very different places than they are today.

A factory is simply a building or group of buildings where something is manufactured, whether entirely by hand, entirely by machine, or something in between. Many historians consider the earliest example to have been the Arsenale di Venezia, a shipbuilding and arms-making complex in Venice, Italy, opened in 1104 A.D. It operated with a kind of water-borne assembly line — ships moved along a canal, being fitted with different pre-made parts at each one — and at its height employed 16,000 workers.

Modern factories grew out of the Industrial Revolution in England. Matthew Boulton’s Soho Manufactory, opened in 1766 in Birmingham, is considered to have been the first one in the modern age (it produced metalwork, vases, coins, and other objects).

The first American factory was a textile manufacturing facility set up in 1790 in Rhode Island by an English immigrant, Samuel Slater. Rhode Island was also the site of the nation’s first factory strike, in 1824 — which was also the first strike of any kind led by women. These are the largest worker strikes in American history.

Click here to see what it was like to work in America’s first factories.

By the time of the Civil War, there were hundreds of cotton and wool factories in the country. Other kinds of factories followed, their efficiency greatly increased when Ransom Olds, creator of the Oldsmobile, built and patented the first modern assembly line in 1901. When the last Olds rolled out of the plant in 2004, it marked the end of what was then the country’s oldest auto brand. These are famous car brands that no longer exist.

The efforts of organized labor have helped make major improvements in workplace conditions over time. Industrial workers still go on strike over issues of salary and benefits, but while problems still exist in factories today, conditions for employees are almost certainly much better than they were in the early days of American manufacturing.

1. Working conditions were better than in England

Though factory work in earlier times could be repetitive, dangerous, and bad for employees’ health, conditions were likely to be better in American factories than in their English counterparts. Working conditions in the U.K. were notoriously bad, and at least some businessmen in the United States tried to create an environment that was safer and fairer.

[in-text-ad]

2. Factory work was still dangerous

Few accurate accountings of work-related injuries and deaths are available from the 18th and 19th centuries (factory bosses had no incentive to record them), but it was estimated in 1913 that almost 25,000 Americans died on the job in factories and another 700,000 suffered injuries that kept them off work for at least a month.

3. Factory fires could be deadly

One of the earliest recorded factory fires in America was in 1878. An explosion at the Washburn A Mill in Minneapolis, then the world’s largest flour mill, killed 14 workers. Another four died as the fire spread to nearby factories. Garment industry fires became particularly common. The most tragic and infamous of those was the Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1911, in which 145 workers — mostly immigrant teenage girls — perished.

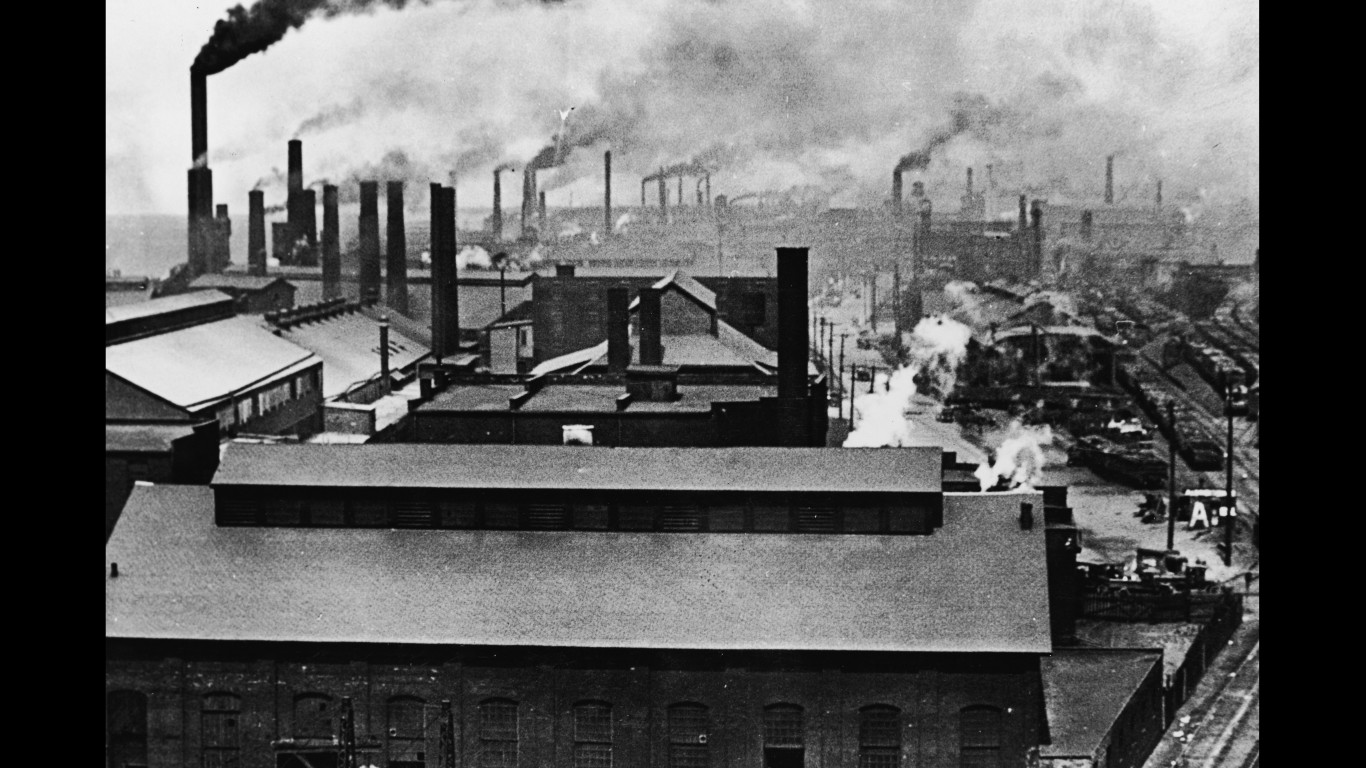

4. Air quality was often poor

In winter, when the natural light died early, factories were frequently illuminated with smoky whale-oil lamps, and machinery ran on steam produced by wood or coal fires. In textile factories, where dry air could cause threads to break more easily, windows were sealed shut and the environment was kept very humid, further degrading air quality.

[in-text-ad-2]

5. Factory employees were used to working on farms

Until the early 19th century, most American workers were farmers, used to working on their own schedules and profiting directly from their labors if they had a good harvest. If they left the land to work in factories, even though the hours might be shorter, they found themselves having to work under supervision at a constant pace, and they earned only what their bosses agreed to pay them.

6. There were no assembly lines until the 20th century

Though they may have worked together in a factory setting, workers at first tended to be skilled craftspeople, who would see the product they were making from start to finish. In contrast, in assembly-line factories, workers performed just one or two functions without necessarily ever seeing the finished product.

[in-text-ad]

7. Work was repetitious

On the farm, though labor could be grueling, tasks changed with the seasons and even with the time of day. Making the transition to factory work must have been difficult for one-time farmers, because even before automated assembly lines they typically had only a small number of tasks to perform, over and over and over.

8. There was no workers’ compensation

Though the concept of workers’ compensation — payment by employers for work-related injuries — can be traced back 4,000 years to ancient Sumeria, and was codified in modern times by the Prussian chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, in 1884, it took a long time to come to America. Wisconsin passed the first comprehensive workers’ comp law in 1911, with other states following — though it took Mississippi till 1948.

9. There was no minimum wage

Because there were more job-seekers than jobs in the 19th century, factories got away with paying very little — about 10 cents an hour for many unskilled workers (less for women and children). It wasn’t until the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed in 1938 that workers were guaranteed a minimum wage (low though that may be) and became eligible for overtime pay if they worked more than 40 hours a week.

[in-text-ad-2]

10. Hours were long

It is estimated that agricultural workers engaged in hard labor for eight to 10 hours a day — or from “first light to dark” — for at least part of the year. Factory shifts, in contrast, typically ran for 12 to 14 hours a day, with only a half-hour lunch break. And while workers labored only six days a week, with Sunday observed as a day of rest, the work continued all year long and wasn’t curtailed by bad weather.

11. There were no sick days, vacations, or paid holidays

Once a worker had a full-time factory job, he or she was expected to show up every day except for Sunday. Staying home sick or to take care of a loved one meant losing pay. The idea of giving employees even a few extra paid days off — for any purpose — was inconceivable to factory owners until well into the 20th century.

[in-text-ad]

12. Strikers could be blacklisted

If a factory worker went on strike, he or she could be fired and then blacklisted — meaning that employers would give their names to other factory owners to ensure nobody would hire them again.

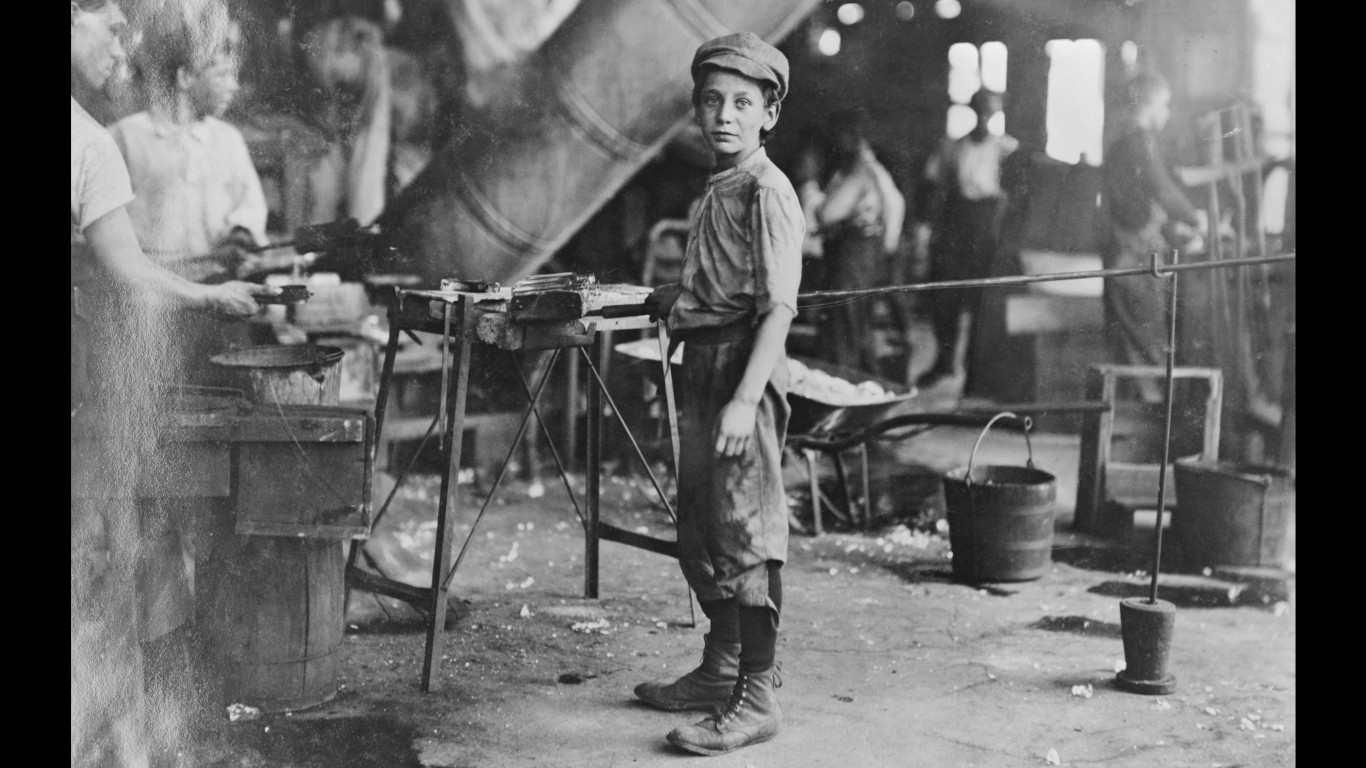

13. Child labor was common

Industrialists liked to hire children. When Samuel Slater opened his pioneering textile factory, for instance, nine children worked foot treadles to power the spindles (they were later replaced by water power). The advantages of employing children included the fact that they were physically smaller than adults, so more of them could fit into a confined space. They could also be paid less than adults. Child labor persisted on a large scale until the Great Depression.

14. Workers could be physically punished

If factory employees in the 1800s were late or broke company rules, they could be strapped (hit with a leather belt) or beaten. This applied to women and children as well as men.

[in-text-ad-2]

15. There were advantages for women

Though they were closely supervised, working in factories gave many women a kind of independence they hadn’t known as children of their parents or wives. Those who had been working in factory jobs tended to make more money, too: Factory wages were sometimes more than double what a woman could earn as a domestic servant or seamstress (though women were paid half to a third of what men were paid for similar labor).

16. Female workers were chaperoned

Early corporations that opened large factory complexes fancied themselves as the moral guardians of the women they employed. For instance, the “mill girls” hired to work in textile factories in New England, who were mostly unmarried farm women aged 16 to 30, were strictly supervised by matrons, given a curfew, and held to a rigid code of behavior.

[in-text-ad]

17. Women working in factories became politically active

What began as protests over labor conditions in New England textile mills, whose employees were mostly women, grew into other reform movements. Mill women signed petitions opposing slavery in the District of Columbia and opposing war with Mexico; they participated in women’s rights conferences; and they joined prison reform campaigns.

18. Workers were seldom well-educated

Coming from an agricultural background, where schooling was a luxury, few early factory workers had much of a formal education. Even in the cities there was little time to take classes, and even children worked rather than studied. It is estimated that by 1915, only 18% of the labor force aged 25 and older had completed high school, and only 14% of those aged 14 to 17 were enrolled in school.

19. Immigrants formed much of the workforce

More than 26 million immigrants came to America between 1880 and 1924, the majority of them poor, and many of them took factory jobs. Most came from England, Ireland, Germany, and Scandinavia in the early 19th century — fully half the workers at the Lowell textile mill in Massachusetts were Irish by the mid 1800s — and later from Russia, Italy, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

[in-text-ad-2]

20. Workers often lived in slums

While some corporations housed workers in company towns — many of them virtual prison camps, characterized by poverty and abuse — these were primarily for those working in remote outdoor locations like coal mines, lumber camps, etc. With some exceptions, most factory workers — who had moved from the countryside into the city — ended up living in tenements and slums. Conditions were crowded and often unsanitary, and electricity, central heating, and even indoor plumbing were often absent.

If you’re one of the over 4 Million Americans set to retire this year, you may want to pay attention. Many people have worked their whole lives preparing to retire without ever knowing the answer to the most important question: am I ahead, or behind on my goals?

Don’t make the same mistake. It’s an easy question to answer. A quick conversation with a financial advisor can help you unpack your savings, spending, and goals for your money. With Zoe Financial’s free matching tool, you can connect with trusted financial advisors in minutes.

Why wait? Click here to get started today!

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us?

Contact the 24/7 Wall St. editorial team.